Huntington Beach, Fountain Valley congregations fight to stay open amid schism over LGBTQ+ stance

- Share via

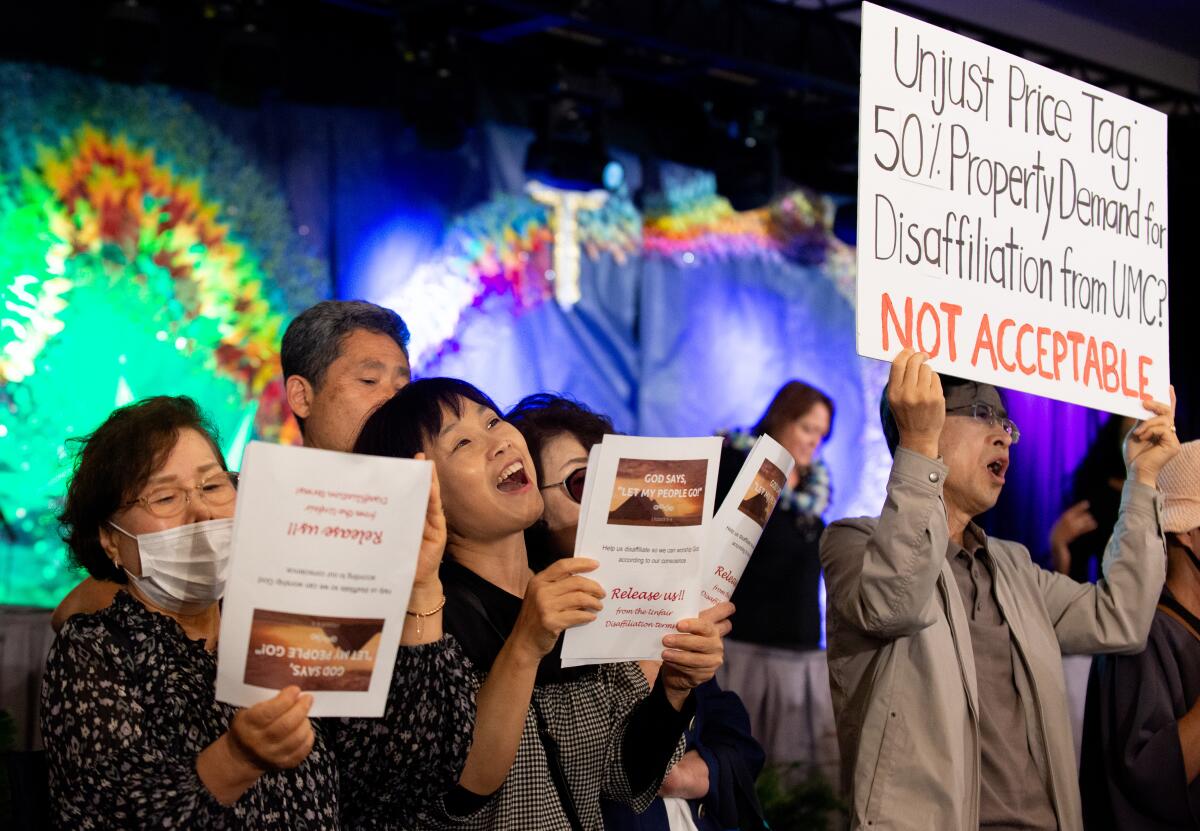

Surf City Church in Huntington Beach, the Fount in Fountain Valley and numerous others whose congregations disagree with the California-Pacific Conference of the United Methodist Church’s inclusion of the LGBTQ+ community into its leadership want to leave the organization, but say they’re being held ransom.

The Fount is one of 22 Southern California churches attempting to cut ties with the denomination in a process called “disaffiliation.” The small Orange County congregation began considering the option shortly after the Western Jurisdiction of the United Methodist Church, which the California-Pacific conference is part of, proclaimed that their region was a “safe harbor” for clergy who identify as members of the LGBTQ+ community, the Fount’s lead pastor, Glen Haworth, said.

“It’s the Bible that we disagree on,” Haworth said during an interview at Surf City Church alongside others trying to leave the conference on June 19. “And the progressive end of the church wants to basically negate all of the teachings of the Bible that have to do with sexual morality.”

He said his congregation’s differences with the UMC lie in their fundamental understanding and interpretation of their faith, not just the conference’s acceptance of gay and lesbian pastors. That’s why the Fount’s members voted unanimously to disaffiliate from the UMC last October.

In the past, that usually meant paying off pensions and any other outstanding dues before going on to either operate independently or join a different denomination, Haworth said. Those were the terms of a protocol drafted in 2019 among churches within the conference to allow conservative congregations to part ways.

But the leadership of the California Pacific Conference has not allowed that deal to come to a vote, Haworth said. Instead, the organization has told the Fount and 21 other churches they must pay half the value of their real estate in order to disaffiliate. Otherwise the conference is claiming the authority to seize the property they worship on.

“This annual conference and a couple others out there are adding onerous provisions for disaffiliation that make it literally impossible,” Haworth said. “My church has 50 members, and they want $3 million dollars. And they say that’s fine, that’s fair. I say: fair to who?”

Conference leadership had revisited the arrangement posed to churches trying to leave, but “ultimately decided to keep the terms the same,” the superintendent of California Pacific Conference’s South District, the Rev. Sandra Olewine, wrote in an email on June 23.

Haworth said he is hoping some other arrangement that might allow the Fount to survive can be worked out before the conference meets in November and votes on whether they will be allowed to disaffiliate.

But he’s not optimistic. Meanwhile, Surf City Church wasn’t given an option.

An “unviable” congregation

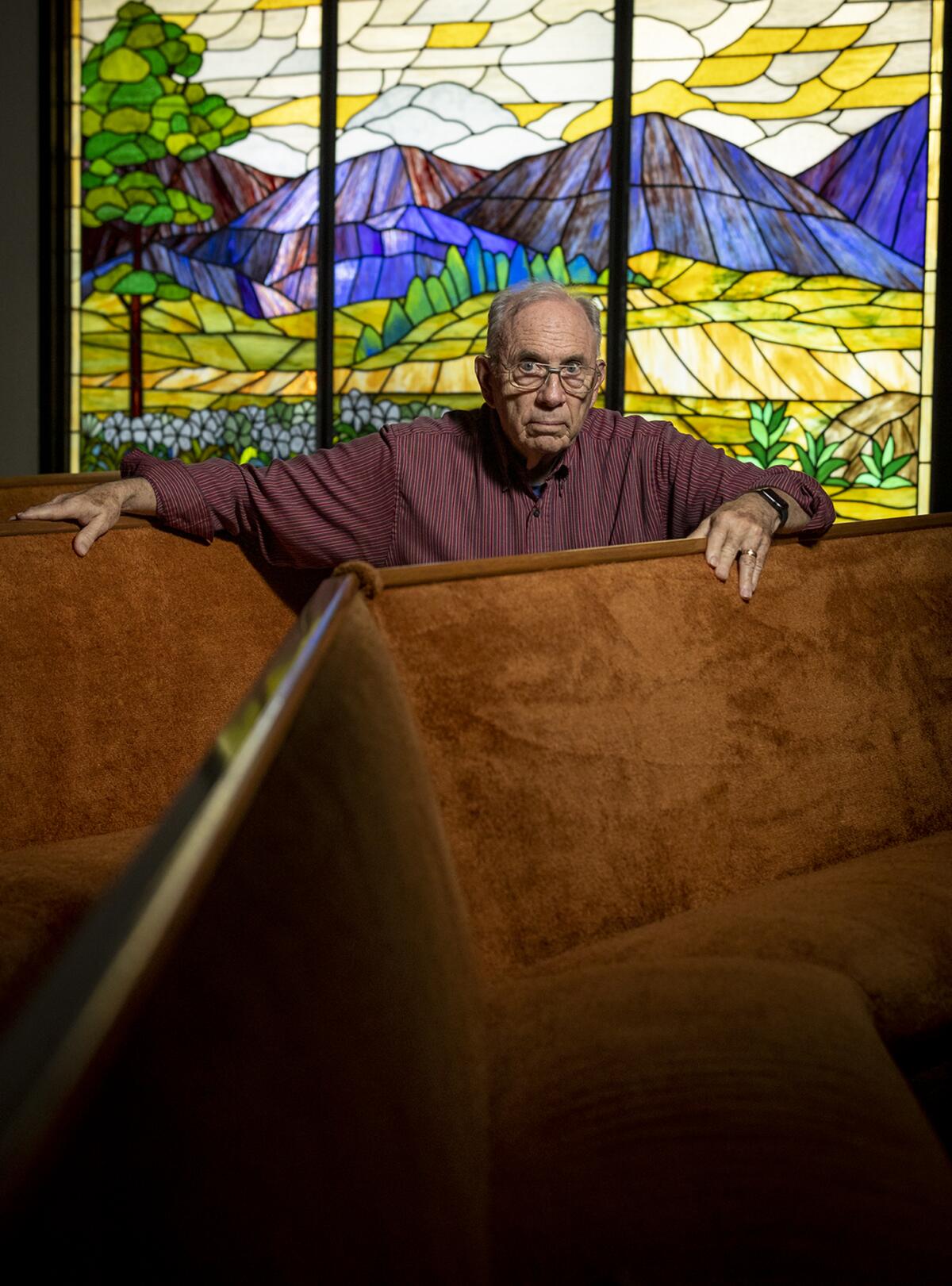

The intersection of Delaware and 17th streets was on the outskirts of Huntington Beach when Surf City Church moved into their campus there in 1967. The residential community that sprang up in the area was, in many ways, built up around the house of worship, John Leonard of the church’s board of trustees said.

They rebranded themselves, taking on their current name and dropping any connection with the United Methodist Church in their public messaging, about 10 years ago, Leonard said. That’s because the Huntington Beach congregation hoped to distance itself from conflict already brewing within the larger organization over its stance on LGBTQ+ issues.

Instead, they focused on concerns within their community. They, along with former pastor Anthony Boger, began streamlining their leadership structure to cut back on red tape and make it easier to organize food drives and other events. They also welcomed partnerships with other churches, including the Well, a non-denominational congregation that rents part of Surf City Church to conduct worship.

When the conference invited Boger to help them expand in Riverside County in 2018, he may have taken it as an endorsement of Surf City Church’s community-centered approach. However, the pastor sent by the United Methodist Church to replace him, Amy Yoon, appeared to toss all of their efforts out the window, Leonard and fellow board member Marge Mitchell said.

Olewine said Yoon was sent to Surf City Church to continue the work Boger had started and further its growth. The superintendent noted that Yoon attempted to create new programs at the Huntington Beach congregation and was working with members who had recently stepped into leadership roles.

Olewine said COVID-19, lockdowns and a subsequent decline in attendance were a struggle for Yoon and the local church to overcome. Those factors created an impossible financial situation, resulting in conference officials’ decision that Surf City Church should be shuttered. Yoon is now the pastor of Chino United Methodist Church.

Leonard and Mitchell said during Yoon’s stint at Surf City, a popular men’s choir and various committees were disbanded. Membership started rapidly shrinking even before the pandemic hit, the Well’s lead pastor, David Housholder, said.

Housholder, Leonard, Mitchell and Haworth suspect the goal of placing Yoon at the congregation was to undermine Surf City Church so that their property might eventually be seized and sold by the United Methodist Church.

“I think the conference and the district have been looking at this property for some time and have lusted after it,” Haworth said. “They’re thinking: ‘If a church gets weak, we can take it over and sell it. We can send someone who’s going to weaken it without them knowing.’”

Olewine, however, said Surf City Church had been deemed “unviable” after “10 years of efforts to revitalize and focus the mission and ministry there.” As a result, a vote was held and the decision was made by conference leadership to close it.

The United Methodist Church’s superintendent added that Surf City Church did not raise the issue of disaffiliation until after its closure was approved, and members labeled unviable are not typically eligible for the separation process.

“If we’re not viable, then half the churches in the OC are not viable,” Housholder said. “This is an active little church. It’s got some resources and history and quite a bit of chutzpah.”

Surf City Church’s leadership were in the process of building it back up when they were summoned by the conference to a meeting to discuss “legacy” in February 2022. Leonard said many of their jaws dropped to the floor when they learned their parent organization wanted them to either shut down immediately, or continue operating temporarily as a “mission church.” The latter meant retaining their identity as a congregation, but selling their current building and possibly resettling in another one later.

They sought a third option: disaffiliation. Leonard requested a meeting to weigh that possibility, but the conference was not receptive.

“We got a letter from [Yoon] saying at the request of the district superintendent ... we were gonna have the meeting, but disaffiliation was not on the agenda.”

The Trust Clause

A “trust clause” included in Surf City Church’s membership agreement with the conference means the larger organization can legally claim all of the local congregation’s property as their own. It’s the basis of a lawsuit filed by the United Methodist Church last November.

Last month, a judge delivered a preliminary decision siding with the conference, Leonard said. They and the Huntington Beach congregation are awaiting a final ruling outlining exactly how ownership will be transferred, although attorneys for the larger organization have unsuccessfully filed motions to allow them to seize it immediately.

During the course of their legal battle with the United Methodist Church, members of the local congregation claim they have been harassed by parties representing their parent denomination, according to Leonard and Mitchell. Earlier this year, they received an email claiming they were illegally operating their preschool and had to shut it down. That was followed shortly thereafter by a visit to the school by state inspectors who said they were responding to an anonymous tip. However, they found no issues.

Surf City Church member Terri King handles the preschool’s finances. When she tried to pay their teachers’ salaries earlier this month, she found out that the accounts holding their wages had been frozen by attorneys for the conference. She reached out to them to get more information but was informed that everything in the building belongs to the conference.

The preschool serves about 95 children from the community, King said. They normally host a summer program, but have decided to cancel it this year “because we have no guarantee that we will be able to pay the teachers,” she said.

Bible study, worship and other programs are still being hosted at Surf City Church with the aid of guest pastors. Members still shuffle into their sanctuary’s pews and take inspiration from its stained glass windows. Most remain committed to their faith, even if they’re practically regarded as squatters by the conference.

“[Surf City Church] is no longer a chartered congregation and due to the failure to participate in the mission congregation process that designation was terminated on December 31, 2022,” Olewine said. “They have no official standing in the denomination any longer.”

A period of reformation

An internal divide over its stance on LGBTQ+ issues along with the challenges of the pandemic have had a toll on the United Methodist Church in recent years, Olewine said. About 20% of their congregations have disaffiliated from the denomination.

The funds generated by churches paying to leave the organization and the sale of Surf City Church’s campus are necessary to ensure that the conference can continue its mission, especially in communities where previous members have disaffiliated, the superintendent said. However, the crossroads the denomination finds itself in may also be a window to modernize.

“The issue of homosexuality and same-sex marriage is the presenting issue currently,” Olewine wrote. “But there are other challenges we must face that have existed for far too long: systemic racism, persistent sexism, and impacts of colonialism both within the U.S. and globally are just a few. How to be church as we approach the second quarter of the 21st century is up for grabs. We are amid a period of reformation, which is not a bad thing, but it is a challenging thing.”

Leonard, Mitchell, Haworth and Housholder believe the United Methodist Church is trying to leverage its survival against what they describe as a ransom on those trying to part ways with it.

“People in the pews, they’re the ones who are just unbelievably disappointed that they were part of a church that would say the kind of things and do the kind of things and take the kind of actions the church has taken,” Leonard said.

He added that Surf City Church existed as a congregation long before it joined the United Methodist Church. Their sanctuary, preschool, fellowship hall and the rest of its facilities were all paid for by members of the community.

“The conference didn’t pay a cent for any of that,” Leonard said.

Founded on shifting sands

Surf City Church started out in 1904 as a “tent church” set up at the shore in Huntington Beach, Leonard said. It moved to its first brick and mortar location on 6th Street and Orange Avenue about 10 years later and then another a few blocks down on 11th street in the ’20s.

King was baptized in that building, and some of her most cherished memories were formed there. She recalled often gazing at a stained glass window that had been donated by the Newland family, which was eventually taken out and reinstalled in Surf City’s current sanctuary.

“When I think of what Jesus looks like, it’s that stained glass window that’s in my head,” she said.

Like many in King’s community, her religion lies at the core of her upbringing and identity. But her local congregation’s conflict with the conference has forced her to reexamine her ties to the United Methodist Church.

“If they close this church down, I don’t know if I’ll ever step foot in a Methodist church again,” she said.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.