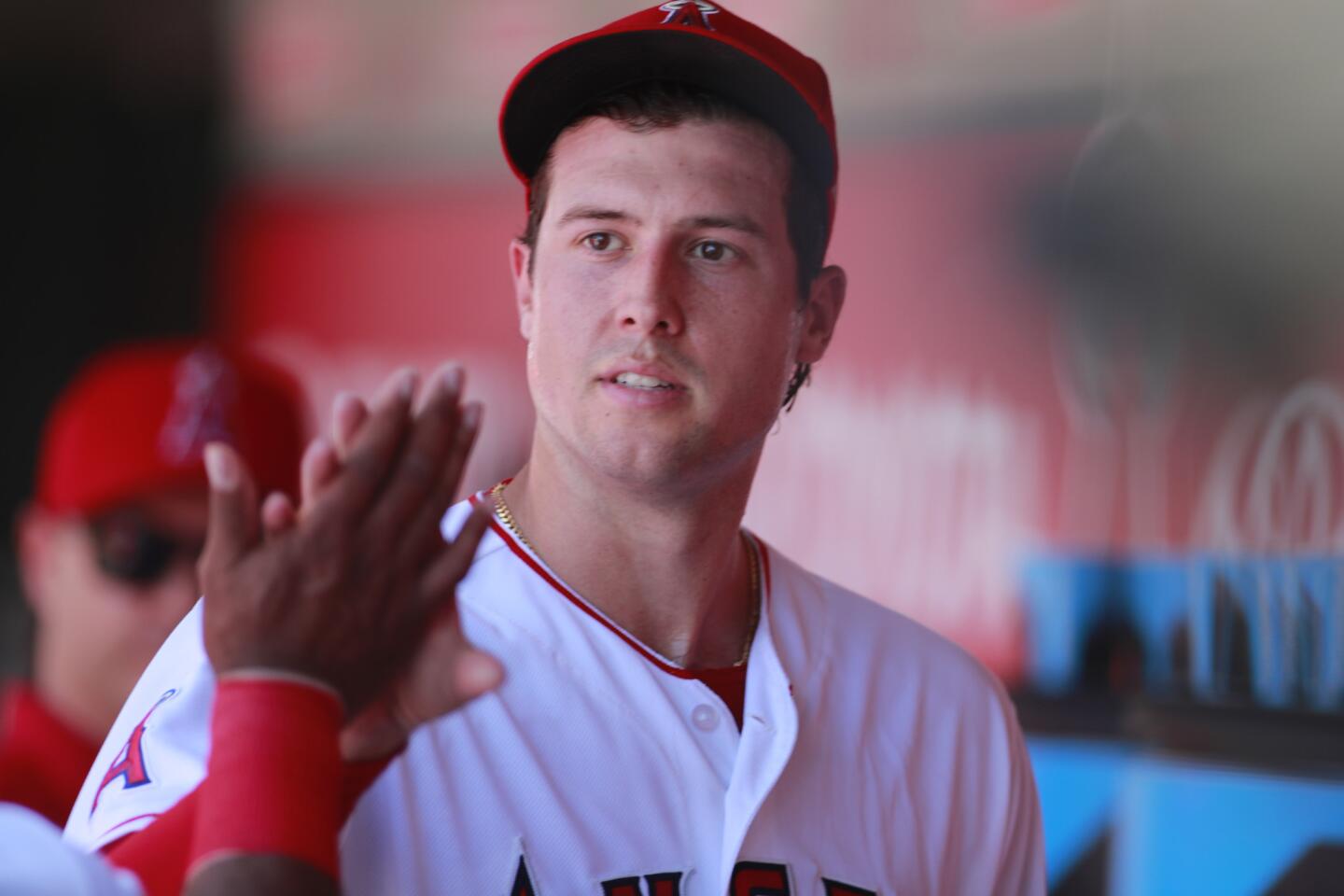

Column: Angels employee’s alleged involvement in Tyler Skaggs’ death is one of many questions

The night continues to defy explanation. In their first home game after Tyler Skaggs’ death, the Angels pitched a combined no-hitter.

From the collective grief emerged the kind of miracle rarely observed outside of sports, starting with Skaggs’ mother delivering a strike on her ceremonial first pitch and ending with the Angels spontaneously covering the mound with the No. 45 jerseys they wore in honor of the deceased pitcher.

The inconceivable sequence of events was a source of comfort for many. People typically fear the unknown. In moments like this, however, that’s where they find hope.

Friday reintroduced a measure of reality to Skaggs’ story.

Tyler Wayne Skaggs died July 1 by choking on his vomit after ingesting a dangerous mix of drugs and alcohol, according to a report released by the Tarrant County medical examiner in Texas.

Fentanyl, oxycodone and alcohol were found in his system.

The revelations were more than heartbreaking, as the newfound discoveries raised a series of questions that will require extensive self-examination on the parts of the Angels, Major League Baseball and society at large.

Skaggs’ family has already started asking questions.

A statement released by the family read in part: “We were shocked to learn that it may involve an employee of the Los Angeles Angels. We will not rest until we learn the truth about how Tyler came into possession of these narcotics, including who supplied them.”

The implication is obvious. The family thinks the drugs might have been supplied by an Angels employee.

General manager Billy Eppler declined to comment on that, citing an ongoing investigation into Skaggs’ death by the police department in Southlake, Texas.

“Can’t compromise the jobs people have to do,” Eppler said.

Eppler also refused to say whether the employee referenced by Skaggs’ family was still employed by the team.

Eppler stated the Angels are “cooperating” with the police investigation but wouldn’t say if the organization was conducting a fact-finding mission of its own.

With the Angels’ locker room off-limits to reporters before the game, Eppler and manager Brad Ausmus spoke on behalf of the organization, fielding questions in the Angel Stadium interview room, where a black curtain was draped over the sponsor-adorned backdrop. Neither had much to say.

Asked if he knew whether this was an isolated incident or part of a larger problem on the team, Eppler replied, “I couldn’t tell you.”

The Angels and the commissioner’s office better find out. America’s problem has become baseball’s problem. Preparing others to avoid Skaggs’ mistakes will require them to know what happened and how.

Part of that is learning the circumstances under which Skaggs started using opioids, whether it was to manage pain or for recreational purposes.

Sign up for our free sports newsletter >>

Fentanyl, in particular, had already claimed the lives of celebrities such as Prince and Tom Petty.

Prince died after taking what he thought was Vicodin but was in fact a counterfeit painkiller laced with fentanyl, according to a Minnesota prosecutor who declined to press criminal charges related to the incident.

Petty suffered an accidental overdose from mixing medications that included fentanyl and oxycodone. The musician was said to be dealing with serious ailments, including a fractured hip.

The Angels were in Texas when Skaggs died, which leads to questions about how the drugs were acquired. If the drugs were purchased on the road, how? From whom? Or were they transported from Anaheim along with bats and baseballs?

“I’d be speculating, you’d be speculating,” Ausmus said.

Angels pitcher Tyler Skaggs’ autopsy reveals intoxication by opioids and alcohol when he died July 1 in a Texas hotel room, according to the medical examiner.

Skaggs’ death should also force the team and league to question if they are doing enough to educate players about drugs.

“I can tell you that I have personally spoken with players within the organization, just in general about life responsibilities and things of that nature,” Eppler said. “Education’s an important part of what we do in a lot of things.”

But educating others requires familiarity with the subject, enough to at least be able to give young men with millions of dollars more than the no-duh speech about not doing drugs.

“Quite frankly, I had to Google what fentanyl was,” acknowledged Ausmus, who has an Ivy League education.

The process of discovering what happened to Skaggs will be uncomfortable, with each revelation likely to be as disappointing as the last. But this is a journey that has to be taken, and not only to provide Skaggs’ family with answers.

The opioid epidemic that was once viewed as a rural, low-income problem has spread everywhere. Skaggs is evidence of that. His story could be instructive for others, but for that to happen, more about his death needs to be learned.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.