How Vin Scully helped me learn English and kept my Mexican American family together

When your parents are immigrants, you generally grow up speaking their language, be it Cantonese or Mandarin, Korean, Armenian or Spanish.

You close your eyes, drift into slumber, and that language carries you into your dreams.

But there comes a point where one door closes and another opens. You don’t dream so much in the language of your parents. You begin to dream in English.

That happened to me right about the time I became a Dodgers fan. I was 6, just starting school at Sheridan Elementary in Boyle Heights, and the narrator of those moments I so desperately wanted to happen — that baseball I wanted to see soar over the center field wall at Chavez Ravine — was Vin Scully.

His voice carried me through dreams where it was me, not Kirk Gibson, who got the big hit that brought glory and happiness to my city.

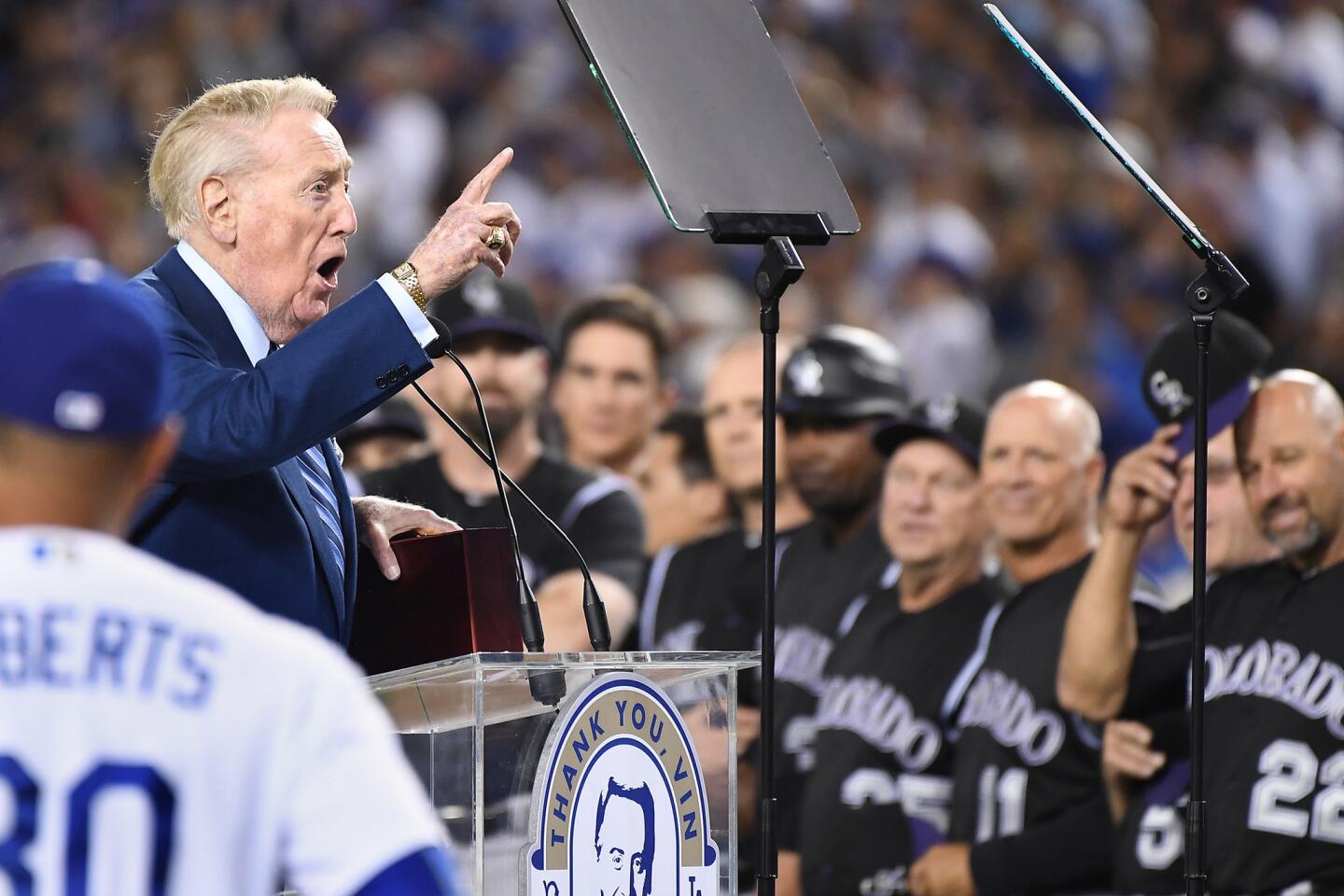

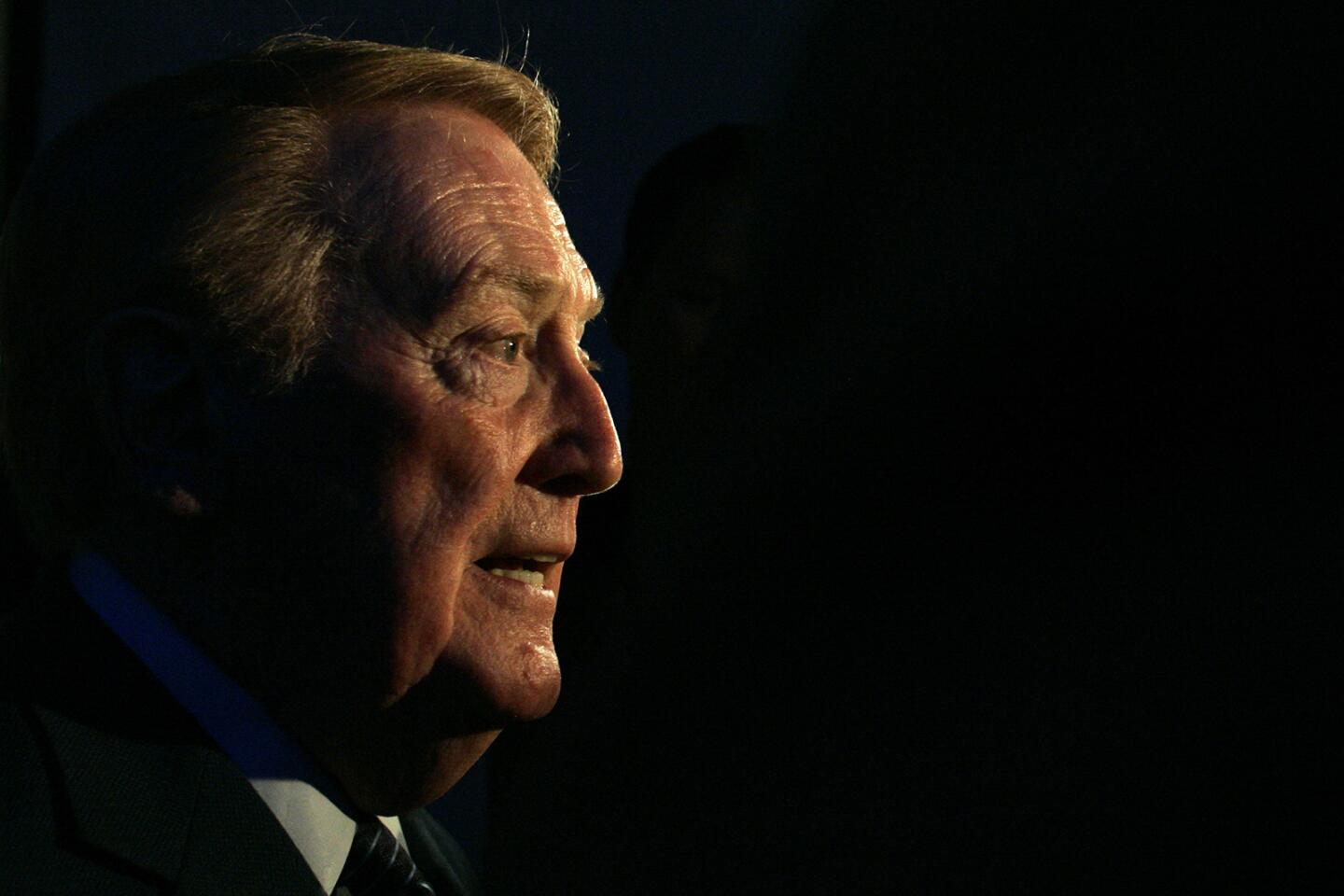

Scully was the first broadcaster I listened to regularly, and he sounded like no one I had ever met or heard. He brought alive the exploits of Steve Garvey, Dusty Baker and my favorite, Pedro Guerrero.

As much as school, sports and an endless loop of Bugs Bunny cartoons, he taught me English.

And there was no better tutor than a broadcaster who sounded like someone shoved Lord Alfred Tennyson into a broadcast booth and planted him in front of a microphone.

I became trilingual: I spoke Spanish, English and sports.

In a humble but meaningful way, Scully and Dodgers actually helped our family stay together, too.

My late father came to the U.S. in the trunk of a car in 1965, and he didn’t do it for the thrills. He had no legal papers. My mother came a couple of years later with a visa that she ended up overstaying.

They were, in the popular parlance, “illegals.” With her came my older brother and sister. I hadn’t been born yet, and as “anchor babies” go I was a pretty half-hearted one, being born seven years later.

Crossing the border illegally in the 1970s and early ’80s, though far easier than now, was no slam dunk. So if we ever visited our parents’ hometown of Jalisco, Mexico, the children were divided among several vehicles to lessen the likelihood we would all go down in one ship if we got caught. My younger sister and brother, like myself, all were American-born. But my older siblings had to fake being American.

How did a boy or girl fake being a United States citizen without official documents? My older brother Javier recalls what happened in the summer of 1977, on our family’s return trip home after traveling to Mexico to finally meet our paternal grandmother.

He was 14 then, 52 now, but still vividly recalls the experience — and the anxiety.

“I had lived in Los Angeles ever since I was 2 years old. It was the only home I knew,” he says. “Still, I had no legal right to live in Los Angeles. My parents had agonized in allowing me to join my sixth grade classmates to an end-of-year San Diego Zoo trip. Too close to the border and border agents.”

As our family attempted to cross back into the U.S. at the Mexicali to Calexico border, Javier and my sister Patricia were passengers with distant relatives — people they had just met — who had visitors’ visas. They had been coached to say “I am a United States citizen.”

“When we reached the border our drivers handed their visas to the agent and told him that we had visited them and were now returning to Los Angeles,” Javier recalls. “I was sitting on the car seat closest to the guard. He leaned into the window.”

“Which is your favorite baseball team?” the guard asked.

How lucky could my brother be?

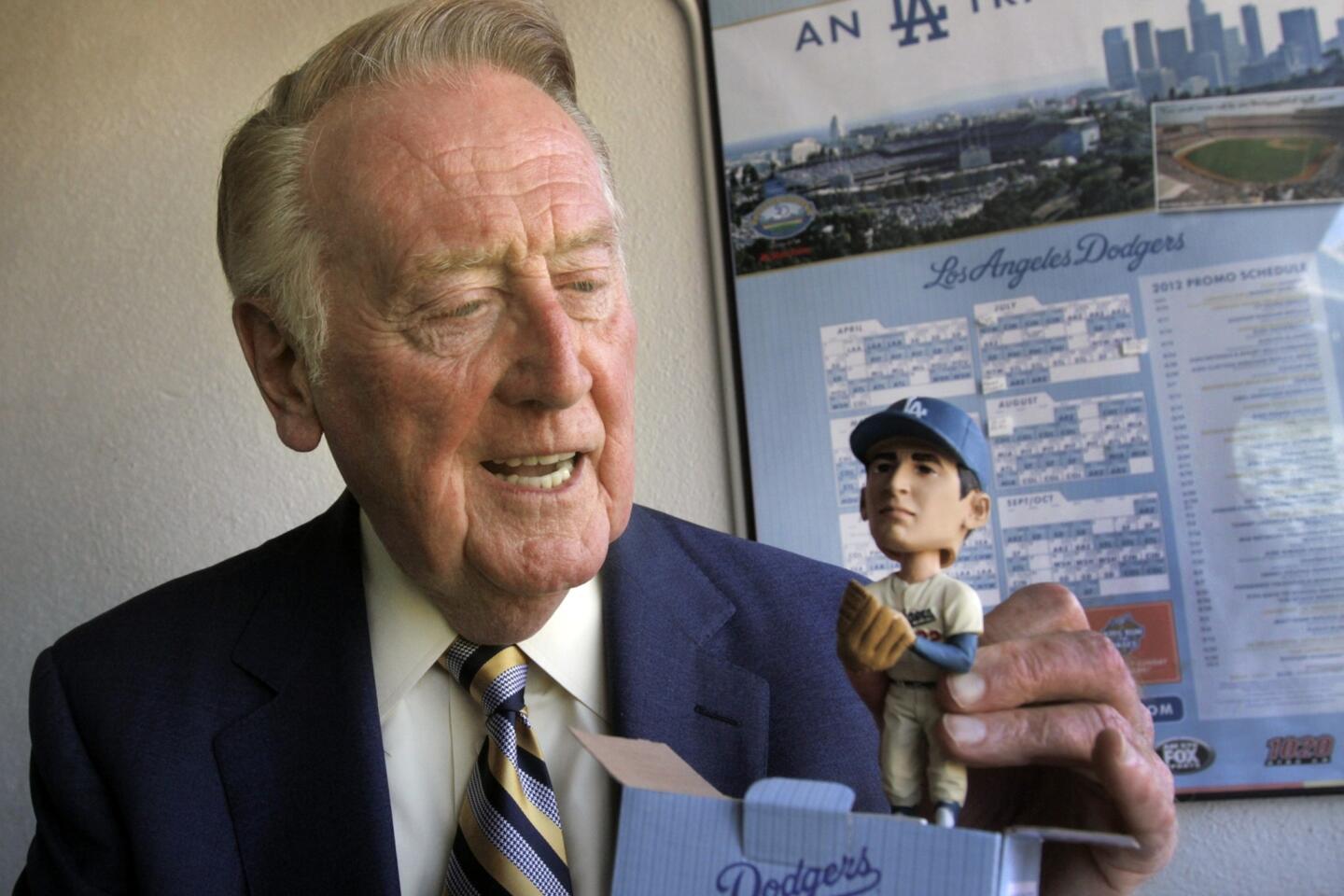

“1977 was a great time to be a Dodger fan,” Javier remembers. “They would win the National League pennant from 1977 through [1978] and the championship in 1981. I spent countless summer days and nights listening to Vin Scully on my transistor radio. I had that answer cold.

“I replied with enthusiasm: the Dodgers!”

The border guard waved the car through. Welcome home to America.

“In the Dodgers, I felt a sense of community,” my brother says. “I was part of something special. Not a trespasser.”

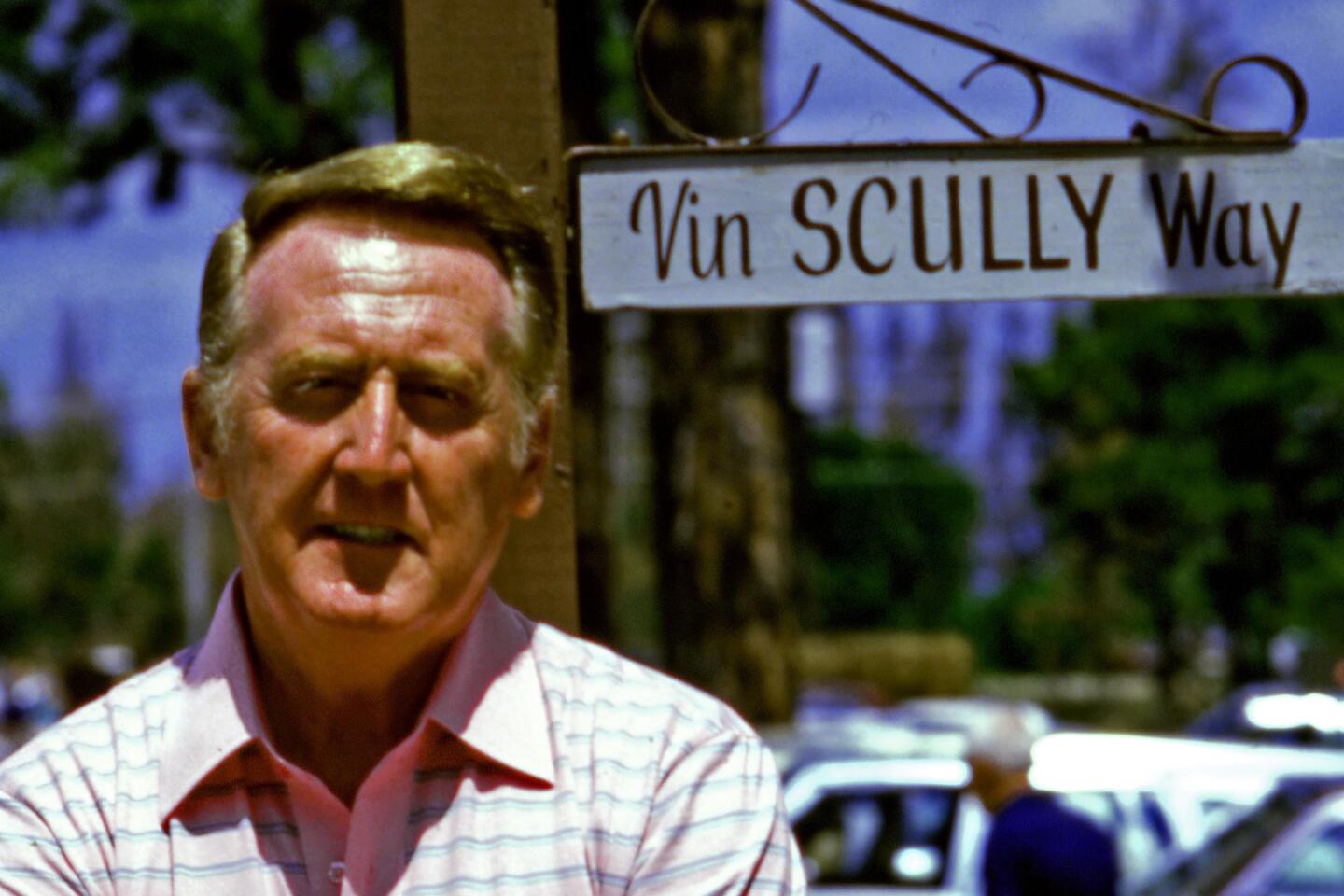

As for me, I don’t know how old I was the first time I got to go to Dodger Stadium. I do remember hearing Scully’s voice coasting through the air, from radios and from speakers.

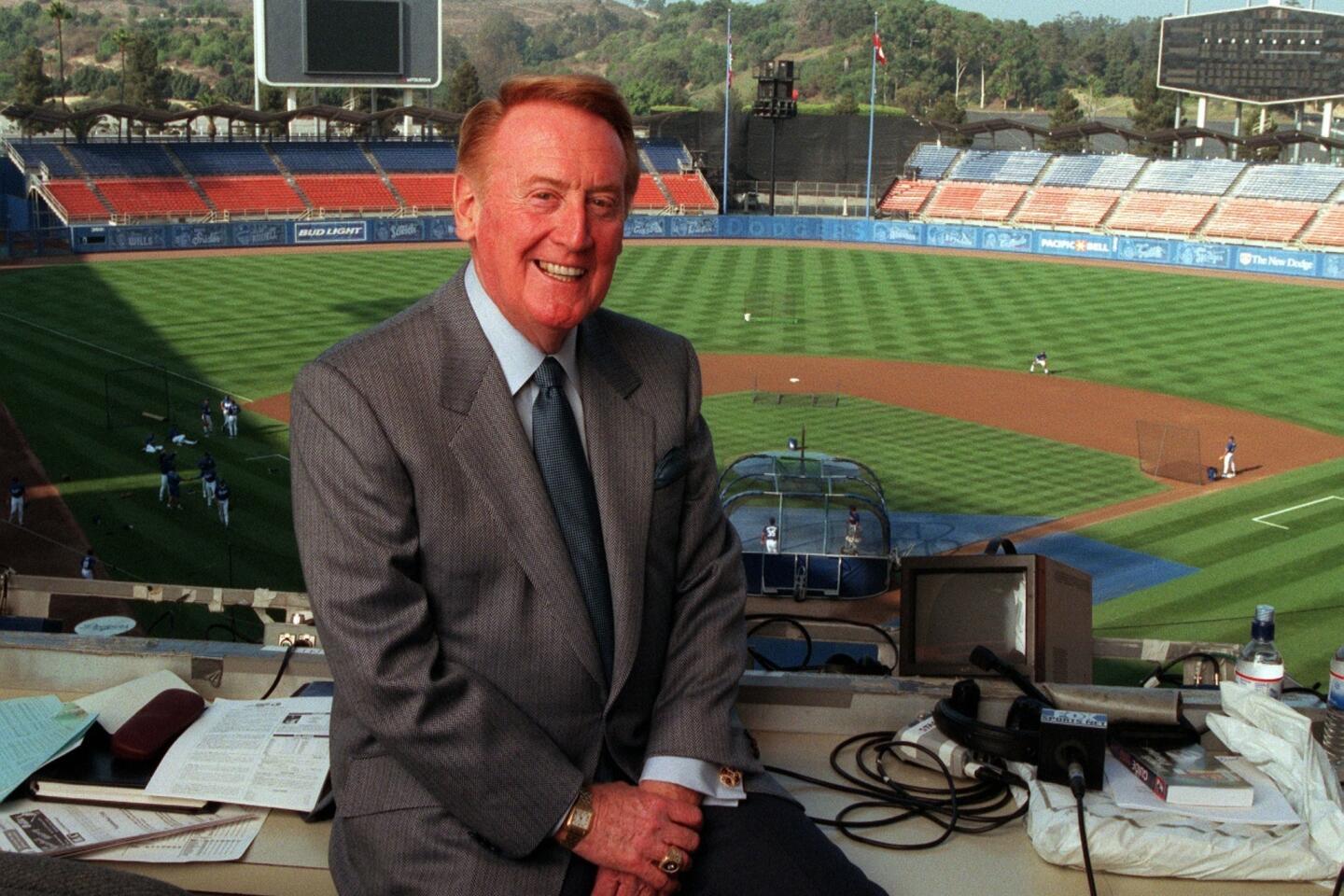

As I always do, I’m sure I squinted into the press box above, like someone trying to peer through clouds pierced by sunlight, trying to steal a glimpse of the man with the voice of a sports god.

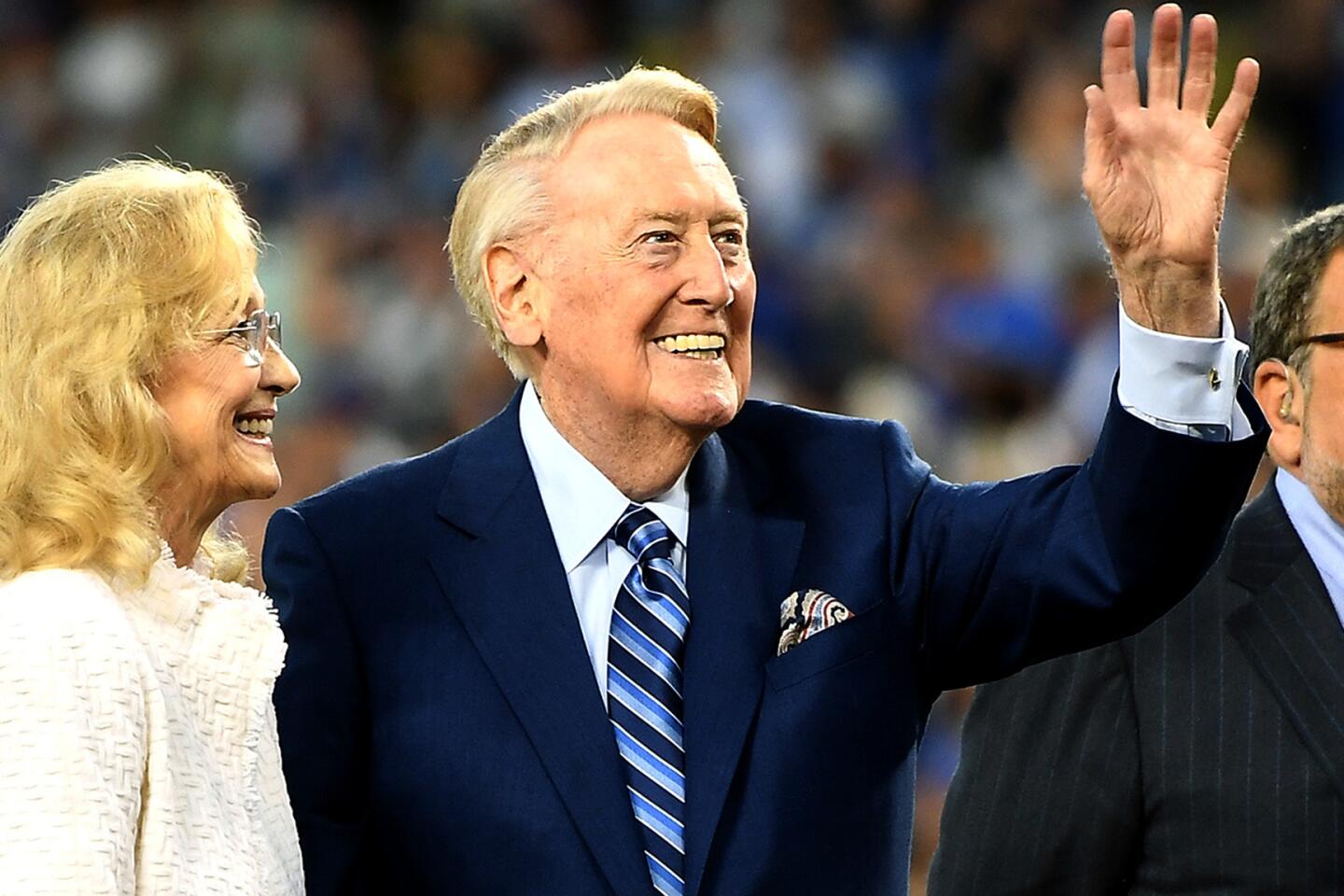

In October 2013, I finally got to meet Scully. I was doing a story on his Spanish-language counterpart, the great Jaime Jarrin. I stumbled upon Scully as he walked in the press dining area of the stadium, and asked him about Jarrin.

“He’s not the Spanish Vin Scully. He is what he is, Jaime Jarrin. He stands on his own two feet. He’s a Hall of Fame announcer and a wonderful human being,” Scully said graciously.

I thanked him and shook his hand — and then looked at my phone, which I had used to record the short conversation. It caught his voice, but not his face. Unfortunately, the video lingered on Scully’s tie.

What can I say? It’s hard to stare straight into the sun.

hector.becerra@latimes.com

Twitter: @hbecerraLATimes

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.