Voice of Dodgers announcer Vin Scully is sweet music to the ears

Chris Erskine and two USC music professors take a look at Vin Scully’s melodic play-calling style.

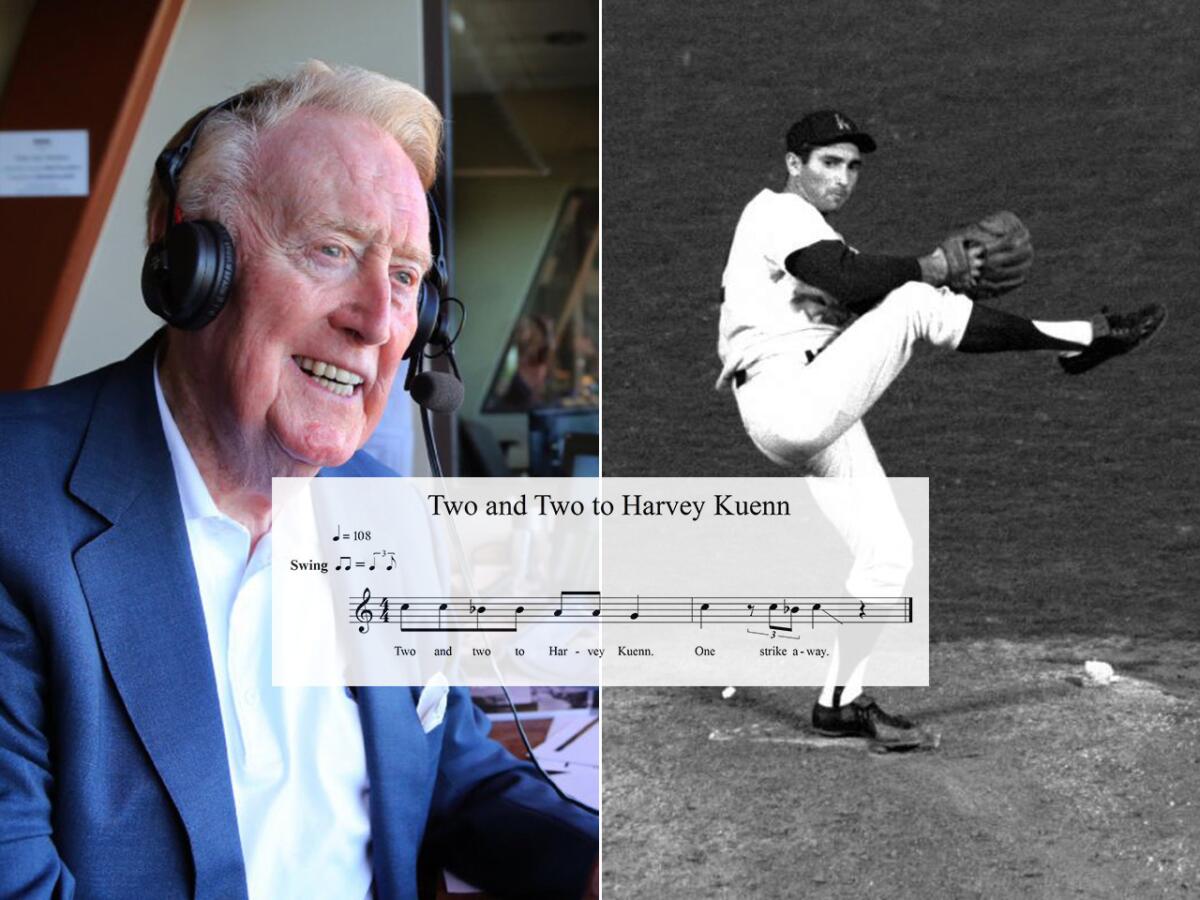

Tonally, he's a tenor. Spiritually, he's Frank Sinatra.

Across seven decades, Vin Scully has bewitched baseball fans with That Voice — full of swing, moxie, and sonic opulence. He uses it like a horn, to serenade an antebellum sport that is too slow by half and make musical the specter of grown men mostly standing around for three hours.

In short, the kid can really sing.

"I hear boogie-woogie," says Chris Sampson, vice dean for contemporary music at USC's Thornton School.

Indeed, two USC music professors, asked by The Times to analyze the musicality of Scully's famous purr, found that the Dodgers broadcaster brings to mind the same cadences and rhythmic hooks heard in great songs. After studying audio clips of Scully's calls, the professors found that his play by play involves rhythm, dynamics, build — all the traits of irresistible music.

"It's swinging," Sampson says of Scully's voice. "In every instance that I've heard, he's always had swing to it."

The crooner's lyricism can probably be traced to the big-band era of his youth. Scully says he has always had a love for the greats he grew up with: Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey, Bing Crosby, Nat King Cole and, of course, Sinatra.

Voices are comprised of brilliance and depth, a dark quality and a light, and he's got great balance of that.

— Jeffrey Allen, assistant professor of voice at USC

"I also love Broadway musicals to this day," he says.

At Fordham, the school's center fielder was also a member of the Shaving Mugs, a barbershop quartet. But Scully scoffs at the idea that he has much in the way of musical gifts.

"Good grief, I must be the only [person] who is off key while speaking," he says with typical self-deprecation.

The music professors disagree.

"It's just amazing how he stays in cadence," says Sampson, who studied several of Scully's calls for rhythm, key signatures, tonality.

"He's not only giving color analysis, he's giving a concert," says Jeffrey Allen, an assistant professor of voice.

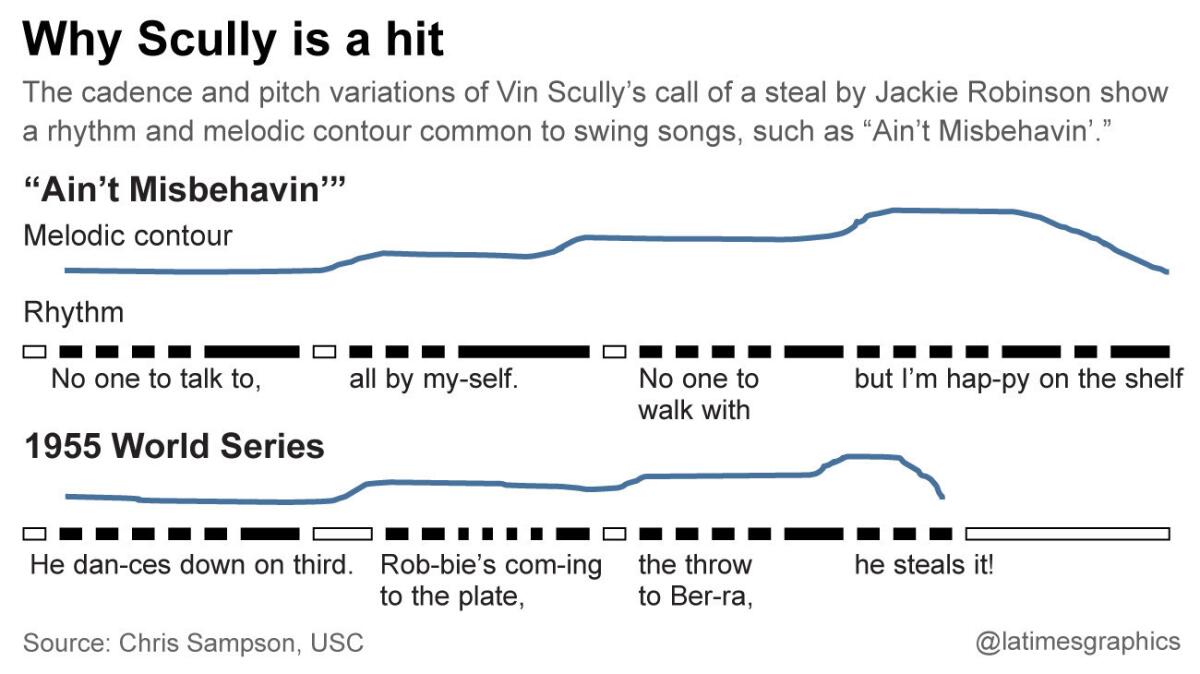

In a music building at USC, Sampson snaps his fingers as he locks on to the rhythms of several of Scully's famous calls. Of a clip of Jackie Robinson stealing home in the 1955 World Series, he zeroes in on Scully's phrase, "He dances down on third."

Sampson says it's the sort of alliteration you'd find in a pop song. In fact, he finds the musical progression reminiscent of "Ain't Misbehavin'," a 1929 swing hit.

"He basically kept the same pulse, the same tempo, all through the piece," Sampson says.

Once he found the pulse to the snippet, Sampson was able to super-impose Scully's call over a boogie-woogie piano beat. The enhanced audio clip made Scully's call of Robinson stealing home sound like the lyrics to a song.

Allen explains Scully's vocal abilities this way:

"The cords compress the air in a very natural fashion … there's no muscling of the instrument. It's just organic. It just flows through him.

"You're dealing with a virtuoso instrument."

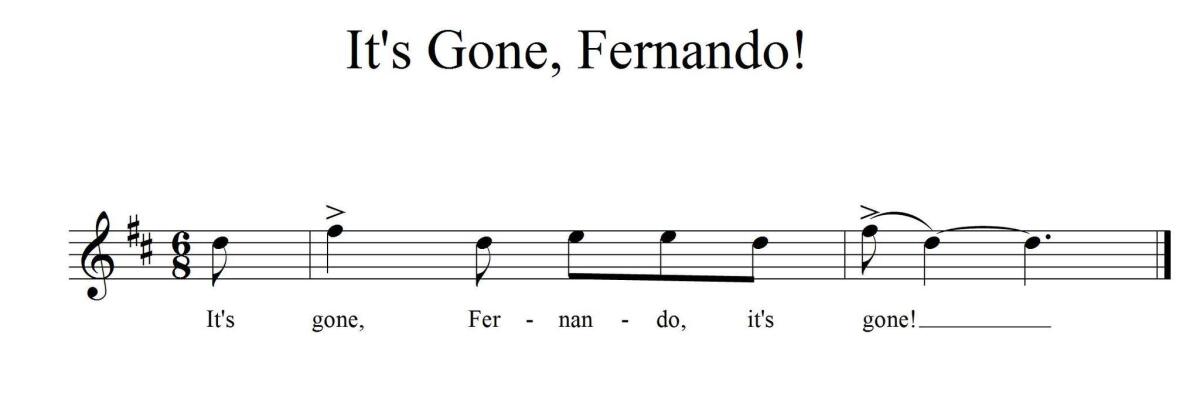

Sampson's analysis included another clip of a game-winning home run that preserved a Fernando Valenzuela victory during the height of Fernandomania.

"It's gone, Fernando, it's gone," Scully says as the crowd roars, a phrasing Sampson says came in three-quarter time, like a waltz ... 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2-3.

"The reason we songwriters use a pattern is to make a song memorable," Sampson says. "I think people remember these game moments because of Vin's musicality."

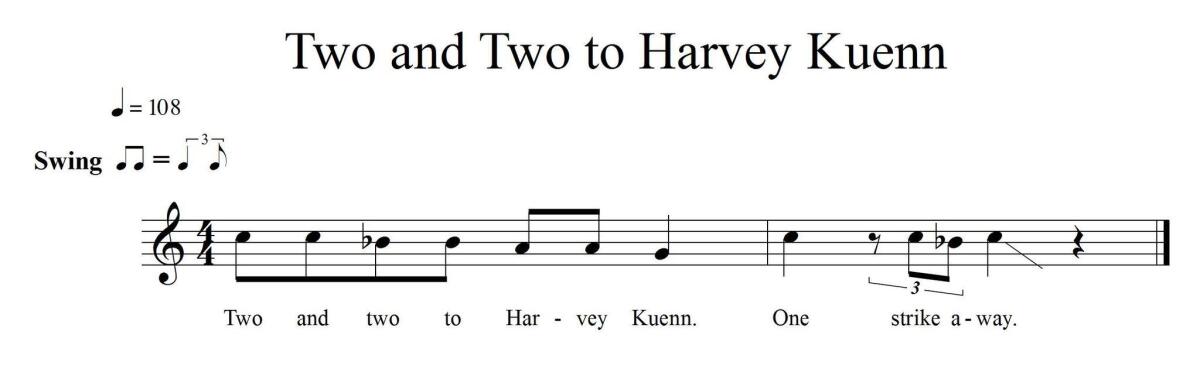

At his computer, Sampson runs clip after clip of Scully's calls. On the last out of Sandy Koufax's perfect game, Scully warbles, "two and two to Harvey Kuenn, one strike away." Again, Sampson snaps his fingers at the rhythm.

To be satisfying, music, like architecture and like movies, relies on structure. Sampson describes a typical Scully progression this way:

"He starts with a dominant chord, and the dominant chord inherently has some tension to it that's leading to a resolution. And so this tension is leading up to something big."

Over and over, the music professors marvel at how Scully can anticipate a game's pivot point, and the way he uses his voice, like the swell of an orchestra, to make the moment cinematic.

"I think Vin has an instinct to know that something's about to happen … so he uses his musicality to build toward that moment," Allen says. "He almost kicks it into gear."

Invariably, the voice professor says, Scully's emotional inflection is "perfectly in tune and tunefully spot-on to the moment he's describing."

That Voice is part of the fabric of Southern California. To hear it, is to know summer is almost on the stove, that everything will be all right for the next few hours.

Meanwhile, athletes come and go, their prime usually lasting a decade at most. Movie stars are much the same way, and recently there seems a dearth of old Hollywood royalty.

Of all people, a humble baseball announcer conquers Hollywood like no one else? It is the long shot of long shots, and something to ponder as he takes his last, bittersweet lap after 67 years with the Dodgers.

"He's the biggest star in this town," says Paul Bloch, a veteran publicist who has repped such stars as John Travolta and Bruce Willis. "He's a modest man, who walks among giants. But he's the biggest giant."

What's makes a folk hero? Presence. Authenticity. Bloch mentions the tone Scully sets as a reason for the announcer's longevity. There is a sagacious Irish verve. Wit meets wisdom. Here and there, some good old-fashioned schmaltz.

Longtime Grammy producer Ken Ehrlich has seen his share of star power come and go. He attributes Scully's longevity in part to his eloquence and voice quality, but also to a sense of elegance.

"He always looks like he stepped out of the pages of GQ," Ehrlich says. "Granted a GQ from the '50s, but there is seldom a hair out of place.

"The other thing is there's the humility, and it's true humility," Ehrlich says. "It comes from a much deeper and honest place.

"For me, that's what it is."

Back at USC, the music professors are analyzing That Voice.

"Voices are comprised of brilliance and depth, a dark quality and a light, and he's got great balance of that," Allen says.

"I call it the 'claw mark,' " the voice professor says. "When you hear one note, you can tell it's that person. McCartney. Elton John. He's got that same sort of claw mark. It can only be him."

Though flattered, Scully himself is skeptical of all the academic analysis.

"Too clever for me," he says after seeing the clips and the musical overlays that Sampson added.

Overthinking it? Perhaps. But that's what baseball fans do. Besides, it's all there in the musical transcription on Sampson's sheet music: "Two and two to Harvey Kuenn, one strike away."

"In all of these clips, something jumped out as musical," Sampson says.

Follow Chris Erskine on Twitter: @erskinetimes

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.