Braves star Freddie Freeman’s formative years in Orange marked by tragedy and support

The face covering he wore during a video call in advance of the National League Championship Series couldn’t hide Freddie Freeman’s emotion.

Asked how his time at Orange El Modena High School shaped him as a ballplayer, the Atlanta Braves slugger’s voice cracked as he recalled a bittersweet period of his youth when he emerged as a top prospect while struggling with the loss of his mother, Rosemary, who died of melanoma in 2000, when Freddie was 10.

“My time at El Modena is absolutely, um … it’s hard for me to put into words,” Freeman, 31, said. “My head coach there, Steve Bernard, is one of the reasons I am the way I am today. He’s a special man, and I hope that he’s watching this, because he means a great deal not only to me but my whole family.”

Freeman’s older brother, Andy, was playing baseball at El Modena when their mother passed away, and Bernard “was absolutely incredible to my brother and my family,” Freeman said. “And when it was my turn to go to El Modena, he really took me under [his wing] and helped shape me.”

Atlanta Braves catcher and cleanup hitter Travis d’Arnaud had a career year at the plate in 2020. The five days he spent with the Dodgers in May 2019 played a role.

Reached by phone Sunday night, Bernard, now an assistant principal at Riverside J.W. North High, was somewhat taken aback by Freeman’s comments.

“There’s not much I can say,” Bernard said. “That’s very kind of him, it’s a beautiful thing to hear, but I do know who Freddie is and what has shaped him, and that credit goes to his dad. The sacrifice he put into his three boys was remarkable.”

Bernard said Freeman’s father, Fredrick, stepped away from his time-consuming job as a certified public accountant to throw batting practice to his sons on his lunch break and again after school two or three times a week.

“He just devoted his life toward his sons,” Bernard said. “He was always there for them.”

Bernard provided Freeman with encouragement, a shoulder to cry on and occasional tough love.

“I remember making him run stadium steps for not doing what he needed to do in the classroom,” Bernard said. “And I do remember — I think it was his mother’s birthday — him having a tough day and giving him a hug and having a conversation with him.”

Freeman’s father is a Canadian citizen as was his mother. His mother was a Toronto native who grew up in Peterborough, Ontario. On a 2015 trip to Toronto to play the Blue Jays, Freeman visited a building where his late mother lived.

“I know she’s watching every single game up in heaven,” Freeman told the Associated Press at the time. “I have a necklace that unscrews and there’s a piece of her hair inside of it, so she’s always with me everywhere I go.”

The memory of his mother was a driving force throughout a distinguished high school career that concluded with a senior season in 2007 during which Freeman hit .417 with five homers and 21 RBIs and went 6-1 with a 1.27 ERA as a pitcher to earn Orange County Register player-of-the-year honors.

“He experienced the trauma of losing a mother, so there were some moments that were tough for him,” Bernard said. “And I think the ability to go and play ball and do it on a daily basis and dedicate himself to that allowed him to get through some of those difficult times.”

A strapping 6-foot-5, 225-pound third baseman and pitcher in high school, Freeman, who bats left-handed and throws right-handed, was a second-round pick of Atlanta in 2007. He passed on an offer to play at Cal State Fullerton to sign with the Braves for $409,500.

“I knew Freddie was gonna be a major leaguer as long as he stayed healthy,” Bernard said. “He had freakish ability.”

It wasn’t just Freeman’s exceptional hand-to-eye coordination, bat speed, arm strength and power. It was his ability to recognize pitches.

“We’re taking live batting practice one day, I’m behind the cage, Freddie is up, and we have some pitchers mixing in fastballs and changeups and curveballs,” Bernard said. “And almost at the exact moment of release point, he’s calling out the pitches, with netting in front of his eyes.

Max Fried, the Atlanta Braves’ Game 1 starter in the National League Championship Series against the Dodgers, started his career in the Encino Little League.

“He’s like, ‘Oh, there’s a curveball, there’s a changeup, there’s this, there’s that.’ I had never had anyone who could identify pitches that quickly.”

Freeman moved to first base in the minor leagues. He reached the big leagues by 2010, finished second in NL rookie-of-the-year voting in 2011 and established himself as a star in 2014, when he signed an eight-year, $135-million extension.

A four-time All-Star, Freeman hit .303 with a .944 on-base-plus-slugging percentage and averaged 30 homers, 39 doubles, 95 RBIs, 98 runs and 79 walks a season from 2016-19.

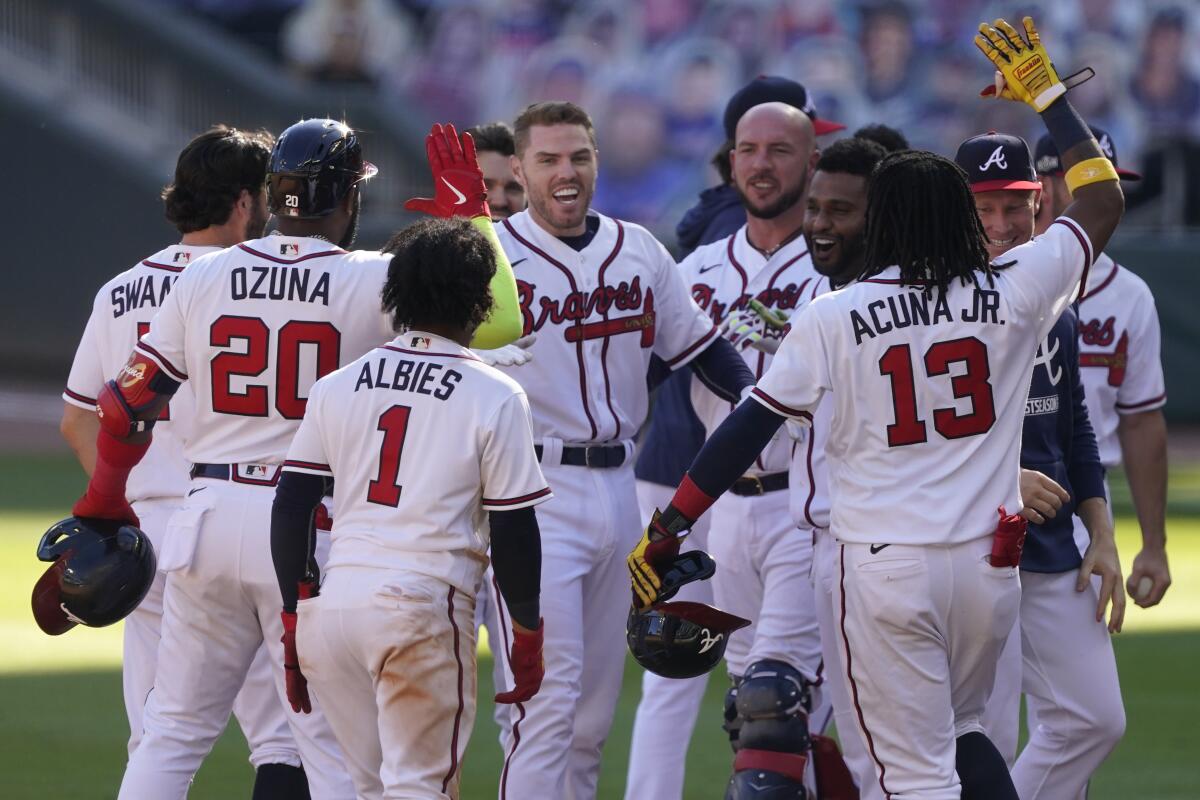

He recovered from a July bout with the coronavirus, in which he experienced body aches, chills and a fever of 104.5 degrees, to play all 60 games this season, batting .341 with a 1.102 OPS, 13 homers, 53 RBIs and a league-leading 23 doubles and 51 runs, establishing himself as an MVP candidate. He homered in the first inning of the Braves’ 5-1 win Monday over the Dodgers in Game 1 of the NLCS.

“I don’t know if you can [quantify] how big his presence is, who he is and what it means to our organization on the field, in the clubhouse, off the field, the man that he is,” Braves manager Brian Snitker said before Atlanta’s division series sweep of Miami. “The guy is some kind of special for all of us.”

Freeman said it “means a lot to me” that his reputation is stellar throughout baseball, “but I’m just trying to get a ring,” he said. “That’s all that matters. It’s nice that people say nice things about you. I think that’s because I’ve been nice to people over the years at first base, so I think they say nice things back.”

Indeed, Freeman is not only a fan favorite and franchise cornerstone, he’s known as one of baseball’s best huggers, of teammates, coaches, front-office executives, opponents and fans.

Like the Dodgers, the Atlanta Braves swept their wild card and division series rounds en route to the National League Championship Series.

One of Atlanta’s most popular giveaways in recent years was a bobblehead featuring Freeman and Hall-of-Fame Braves third baseman Chipper Jones about to embrace each other. One of the dolls sits on a shelf in Bernard’s office.

“That’s the type of person he is, he’s just infectious with his joy and positivity,” Bernard said. “As proud as I am that he’s one of the best players in the game, I’m also proud of the person he is.”

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.