Their coach felled by a stroke, this team rallied for him and became champions

The paramedics came within a minute, Marcus Droz remembers.

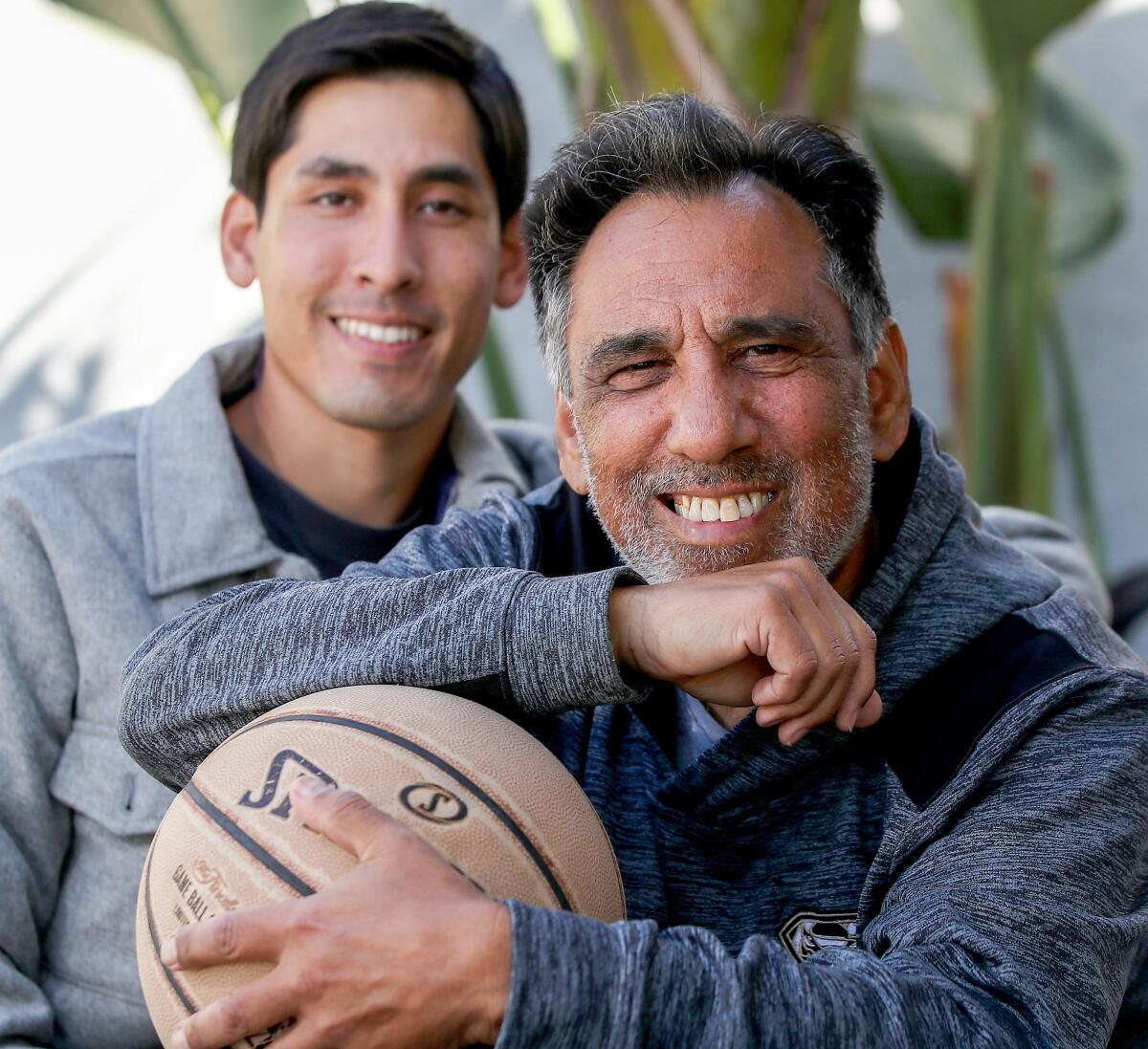

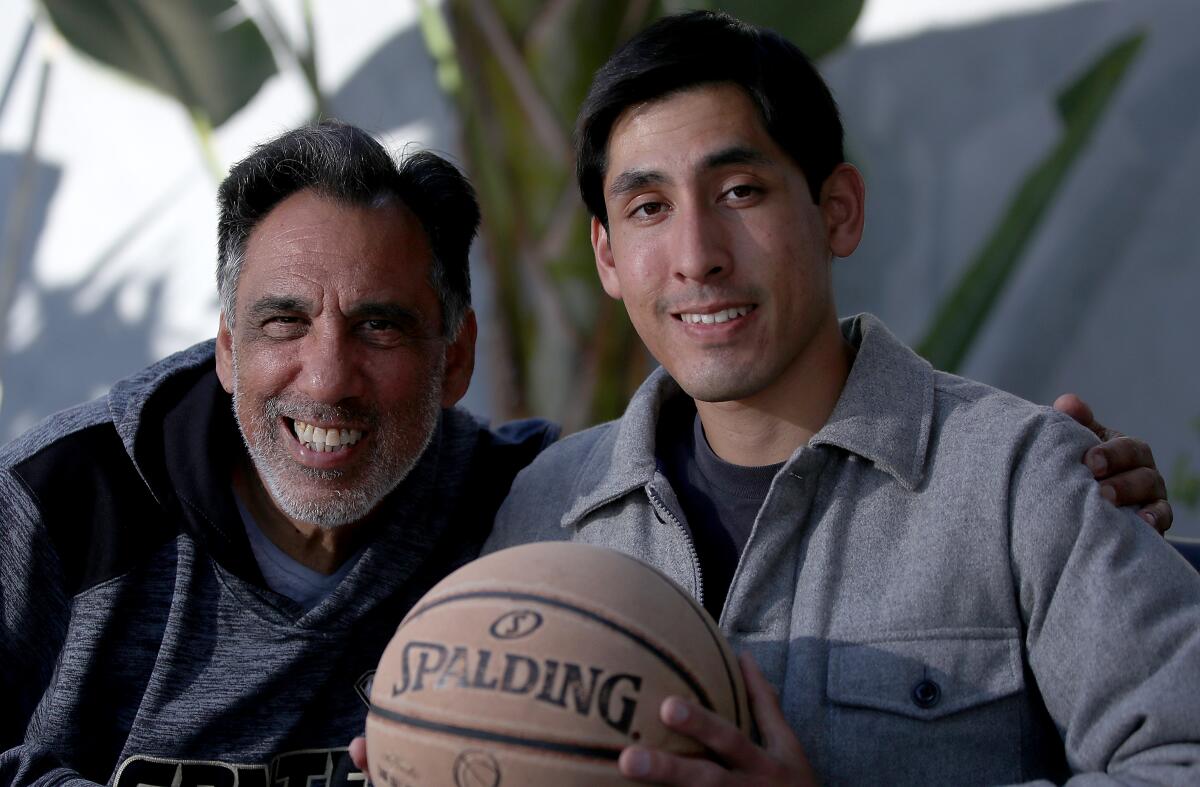

He’d called 911 when his father, Manuel Droz, head coach of the girls’ basketball team at Santee Education Complex, struggled to keep his balance during a game. Manuel was seated but felt like he would topple.

Santee was down 47-41 against John Burroughs High with four minutes left when 64-year-old Manuel slumped forward, catching himself on Marcus’ arm.

“Marc, I’m really dizzy,” Manuel told his son. “I can’t stand up.”

Referees and players stopped to stare at the sidelines, where Manuel started dry-heaving into a trash can as Marcus, his dad’s assistant coach, dialed for an ambulance. Senior captain Marlisa Pacheco and the other girls gathered around, stunned and fearful, as their coach was rushed to the hospital.

Take a closer look at the 12 CIF state championship high school basketball games scheduled for Golden 1 Center in Sacramento Friday and Saturday.

The Santee players had experienced a lifetime’s worth of pain and challenges before they were old enough to vote. Basketball had been an escape, the white Falcons uniform a suit of armor for a team shaping up to have its best season ever.

But on this day, the pain had pierced through. Manuel had suffered a stroke and in the weeks following, the girls came to fight together — to fight for Coach Manny.

“He wasn’t here with us, but we wanted to do it for him,” Pacheco said.

::

Their favorite memories of the season are the bus rides.

Most of the players’ parents work long hours, often two shifts a day, to scrape together money for rent. The school district provided buses only for league play, so getting to nonleague games was an issue. The girls would squeeze three or four deep into carpools usually headed by Manuel and Marcus.

So the buses were special. When the ride back to campus neared its end, the 14 girls would break into song, the same every time:

“We thank the bus driver, the driver, the driver, we thank the bus driver for taking us home.”

Marcus loved it. “No matter how serious the bus driver is,” he said, “they’ll always crack a smile.”

Home for most of the players is in the neighborhoods surrounding Santee, south of downtown Los Angeles. It’s a dangerous area, Marcus said, one that carries the homelessness of downtown and gangs of South L.A.

But it was home, especially to Manuel. He grew up down the street from Santee and bought a house across the street from where he was raised.

“My dad has so much love for the team — half of what he talks about is the team.”

— Marcus Droz on his father’s dedication to Santee basketball

When he started five years ago at Santee as a volunteer assistant coach, the program was mired in an endless losing slump. In 2019, the Falcons, went 11-4, their first winning season since 2007. Manuel hoped to continue the winning ways when he was hired as head coach in 2020.

“My dad has so much love for the team — half of what he talks about is the team,” Marcus said.

On Dec. 28, with the team sitting at 4-1, Manuel and Marcus had struggled to find rides to Burroughs, a nonleague opponent in Burbank. Manuel had been stressed. His blood pressure, long a problem, according to Marcus, spiked and he started feeling nauseated. At halftime, Manuel gave his son the reins, telling him he didn’t feel well. Even before then, Pacheco had noticed something amiss.

“Before I went into the game, I had asked him if he was OK, and he was like, ‘No,’” she said.

Pacheco had met Manuel when she was just 8 years old, playing at the Trinity Recreation Center in South Los Angeles, where Manuel held basketball clinics. Now, the eyes that had watched her dribble around the park lolled to the left or right, unfocused.

And when it came time for the tipoff, the team played on.

::

Junior Jasmine Burghardt’s first-period class was music. Santee’s assistant athletic director, Ruben Martinez, would see her learning to play guitar, fingers inching along the strings like nothing was the matter.

Nobody on the team knew Jasmine’s father had died of cancer over Thanksgiving break. But Pacheco sensed something was wrong.

“I noticed her not being herself,” Pacheco said. “I asked her, ‘Are you good?’ She’d tell me, ‘Yeah.’ I knew she was lying to me.”

Burghardt finally opened up to her teammates on Dec. 28, before the Burroughs game.

“After everything that we’d been through, basketball was able to be somewhere safe — our safe place.”

— Marlisa Pacheco, Santee girls’ basketball team captain

Three months later, she sat in a Santee classroom next to Pacheco and Martinez, struggling to find the words for that day. “My dad passed away, so that threw me off a little bit,” Burghardt said. “The same day I told them that, Manny had a stroke, and then …”

Burghardt bowed her head, sobbing silently. Pacheco’s arm crept around her teammate’s shoulder, the captain’s own eyes rimmed with red, the two drawing in shaky breath after breath together.

It seems every Santee girl has a story. Mary Jane Valles, a senior and the tallest player on the team at 6 feet, has been homeless for much of her life and recently taken in by her girlfriend’s family.

Another player started playing basketball at a young age to escape a house with a meth-addicted brother. Another told Marcus that when she and her sister were younger, they were sexually abused by their mother’s ex-boyfriend.

“I don’t even ask,” Marcus said. “It just kinda comes out.”

Over the season, they became like a “family,” Pacheco said, with basketball their shared haven. The girls enjoy each other’s company, goofing off and joking around at practice.

Marcus lets that go. Inside Santee’s gym, everything outside the white walls can fade away.

“After everything that we’d been through, basketball was able to be somewhere safe — our safe place,” Pacheco said.

::

Santee lost the Burroughs game by default, play having stopped after Manuel fell ill. That night, doctors couldn’t give his family a clear prognosis.

“We had no idea,” Marcus said. “He could have been almost brain-dead.”

The team had a game the next day. After coming home, Marcus called his mom, still in Manuel’s hospital room, to say he wasn’t sure if he should coach the team.

Over the static of the phone, Marcus heard a faint yell in the background from Manuel, barely hanging onto consciousness.

“Yes!”

The next morning, Marcus gathered the girls and gave it to them straight: coach’s prospects were uncertain. The team should focus on the game ahead, he said, and control what they could control.

Their game was against Hart, a team in Division 3AA, a step up from Santee’s regular Division 4 opponents. In California high school basketball, teams are separated by region into divisions that attempt to level the playing field for programs of different strengths.

Santee lost 68-14.

“It was tough regrouping,” Marcus said.

RJ Smith helped LaVerne Damien High win the regional boys’ basketball title Tuesday, his all-around play and unselfishness the marks of a champion.

But the next day, doctors told Manuel’s family that he wouldn’t need surgery and could expect to make a full recovery. But as his dad laid in the hospital for weeks, the 25-year-old Marcus had trouble earning the team’s respect.

“I was kind of fed up with them, to be honest,” Marcus said, “because they weren’t listening to what I was saying.”

After the Hart loss, Marcus set up a group chat over text with the girls that they named “Queen Falcons.” In his first text, he told them to call him “little coach” and his dad “big coach.”

After the holiday break, the Falcons’ next opponent was Diego Rivera Education Complex. Marcus remembers the girls blowing off his game plan, choosing to run a handoff play that he knew wouldn’t work against a zone defense. He tossed his hands in the air and told them to run what they wanted.

Eventually, the girls realized the handoffs didn’t work and turned to Marcus, who started drawing up a play to run against a zone.

Santee won 52-26.

“Since that point on, they’ve had a lot more faith in me,” Marcus said.

::

Manuel had returned home shortly before the Rivera game after a three-week hospital stint that included a positive COVID-19 test. The night of the win, sitting at the dinner table, Marcus excitedly told his dad how the girls finally listened to him.

Every night, Marcus took his dad out to their backyard to continue physical therapy exercises, slowly weaning him off a walker Manuel had affectionately nicknamed “Paul.”

Along with Manuel, the Falcons also found their legs. They carried a three-game win streak into an early February showdown with rival Thomas Jefferson High.

Well, rival was a strong word. The team hadn’t beaten Jefferson in nine years, Martinez said.

Down by 13 in the fourth quarter, Marcus called a timeout after a turnover by Valles. The girls trudged over, heads tilted to their shoes, shoulders caved. Valles, one of the team’s top players, looked defeated.

Earlier that day, while watching the JV girls play, Valles had told Pacheco her story for the first time. How she had had a difficult home life, spending some time in foster care. How she had bounced between family members, staying with whoever would take her in. How, according to vice principal Kymbereley Garrett, she would walk out of the gym after practice and not know where her head would hit the pillow that night.

“When I see her, it’s that self-motivation that she has,” Garrett said. “Like, ‘I’m not going to let all this stuff that happened to me determine my future.’”

During the timeout in the Jefferson game, Pacheco tried to rekindle that motivation in her friend.

“Keep your head up, MJ,” Martinez remembers Pacheco telling Valles. “Don’t quit like you haven’t quit in your life. We’re going to come back.”

Santee outscored Jefferson 16-1 in the fourth quarter and won by three. Three days later, the Falcons played Jefferson again and beat them again, this time by 30.

::

Manuel still has weakness in his left leg and arm, and struggles at times with depth perception. But Marcus said he’s able to walk on his own now, and has no problem eating.

Manuel can talk just fine, too, and he talked to Marcus plenty after every game, always curious how the team did and who played well.

The team, in fact, was doing quite well and had steamrolled through the playoffs. Before a semifinal clash against Sherman Oaks CES, Manuel warned his son the successful press defense Marcus had instituted for the playoffs would no longer work. Sherman Oaks was a great passing team, Manuel said, and would break the defense easily.

Heeding his father, Marcus went back to a man-on-man look. Santee won by 32.

The Falcons kept winning and on Feb. 26, faced Panorama for the Division IV City championship.

The Falcons took the lead, though at halftime they were disappointed they were “only” ahead by 12. They went on to clinch the title with a 62-38 win, and Pacheco led the team in an exuberant chant: “Coach Manny on me! Coach Manny on three! One, two, three, Coach Manny!”

Looking back, Burghardt and Pacheco still haven’t processed it all: the feeling of having their names called as they ran up to receive their medals; the Santee stands chanting each girl’s name with South Los Angeles love; the tears of happiness rolling down their faces.

“Where we come from, we don’t get a lot of wins,” Marcus said.

Tears of sadness followed days later, as the girls lost a hard-fought bout in the first round of the state playoffs to Laguna Beach High. Valles watched from the sidelines after turning her ankle in the first half, and Burghardt and Pacheco shared a dejected embrace walking off the floor.

Juju Watkins has 29 points and plays tough defense to lead Sierra Canyon past Etiwanda to win the Open Division girls’ basketball regional championship.

Pacheco, a senior, said she can’t bear the thought of leaving her teammates after the school year finishes. But she and Burghardt are looking forward to coming back to the Santee gym when they are older and to look up at the banner that will read “City Champions.”

“For us here at Santee, they represent us,” Garrett said of the team. “We’re not some big, fancy school. We’re here in the heart of South L.A. But our kids, they have such determination and goals.”

On the night Santee won the city championship, little coach came home with a medal around his neck and another for big coach tucked in his pocket. But when he came in, Marcus bowed his head to remove his prize and drape the ribbon around his father’s neck, the medal resting just inches above his heart.

Manuel began to cry, Marcus remembers.

“We did it,” Manuel told him, because there were no more words left to say. “We did it.”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.