Celebrating the moms who let their boys grow up to be NFL stars

Celebrating the moms who let their boys grow up to be NFL stars

| Reporting From Philadelphia

Hi, Mom.

Think of the countless times that football players have looked into the sideline TV cameras and mouthed those two little words.

It was in that spirit that DirecTV gathered the mothers of some of the top prospects in the 2017 NFL draft so they could tell their story of raising sons whom millions of football fans will cheer on fall Sundays. For their participation, the mothers received subscriptions to NFL Sunday Ticket and NFLST.TV, a service that will allow them to stream the games of their sons on any connected devices — in case they’re not on hand to watch live.

The Times sat down with six of those mothers to get their perspective on how their sons got to this point, and where they’re headed now:

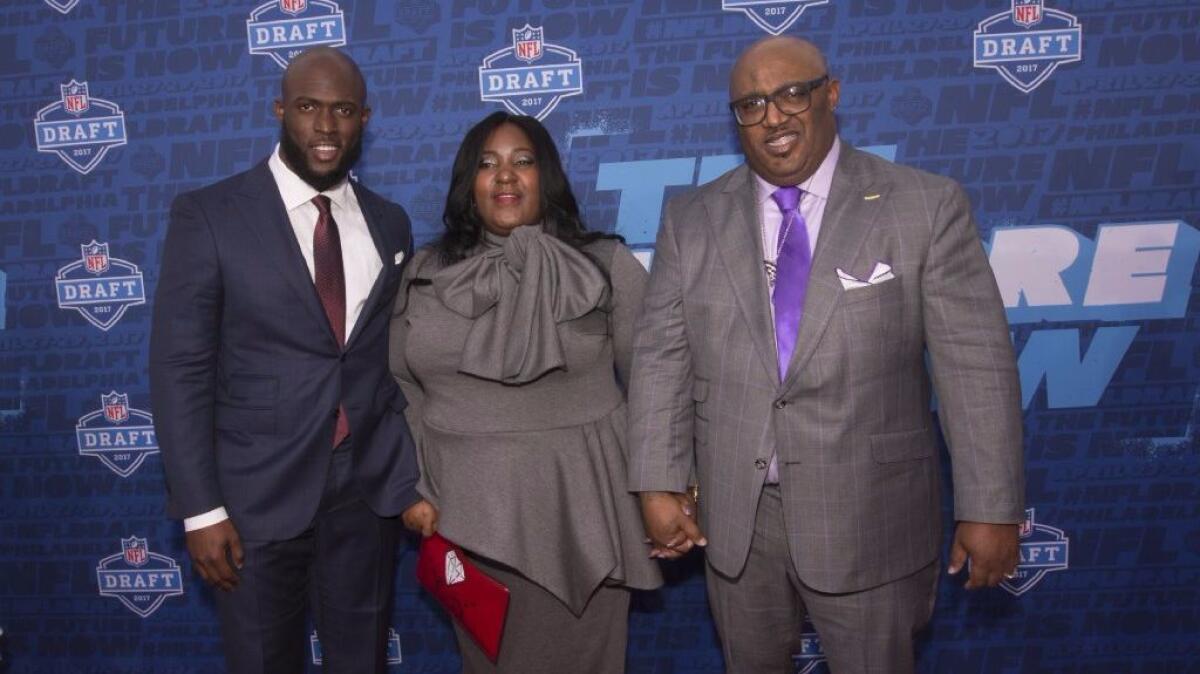

Before the Jacksonville Jaguars took him with the No. 4 pick, there was all sorts of speculation about when and where Louisiana State running back Leonard Fournette would be drafted. Lots of teams were looking for running backs, and Fournette is a 240-pound bruiser.

His mom, Lory, tried to take a break from all the draft chatter, but her husband wasn’t too good about turning down the noise.

“It mostly drove my husband crazy because every time he turned on the TV he was like, ‘What number is he at?’ ” Lory said. “I said, ‘Maybe we should just keep off the TV for a little bit, just a couple days. Enjoy the family and take a vacation from the TV.’ ”

Fournette really broke through early in 2015, his second season as a starter, when he had three 200-yard games in a row. Then last season, he ran for 284 against Mississippi.

“I knew he had God-given talent, but when he almost got 300 yards, I was like, ‘Wow,’ ” his mom said. “He didn’t even have to play the third and fourth quarter. That was it.”

Then, with a laugh: “If they had let him play, maybe he would have gotten 600.”

The draft was especially emotional for Lory Fournette, because she knows what her son overcame to get this far.

“Leonard was a child who stuttered,” she said. “Nobody knows that. He had a stuttering problem real bad. He would always say, ‘Mom, I want to play in the NFL.’ I’d say, ‘You want to be in the NFL? You need to learn how to talk first.’

“I would make him get in front of the mirror. You can ask his siblings. We would make him talk. He would have to speak slowly because, I said, `You’re going to be before thousands of people, and you need to learn how to articulate your words. You cannot stutter, Leonard. They won’t be able to understand you.”

A mother can’t always baby her son. By Fournette’s early teenage years, his stutter had pretty much gone away.

“I’m just so thankful that by me saying that, I actually released it into the atmosphere,” she said. “And now it has come to pass. He’s in the NFL. That is amazing.”

Marshon Lattimore had boundless energy as a kid. Sometimes, too much for his own good.

The former Ohio State cornerback who was drafted 11th by New Orleans spent his childhood in a constant state of motion, running from this place to that, grabbing a chair to do an impromptu set of dips, jumping up to touch the ceiling over and over.

He loved youth football so much, he didn’t want to come off the field to give other kids a chance.

“As a kid, he used to be little stubborn,” said his mother, Felicia Killebrew. “With Marshon, if he had made so many touchdowns and they wanted other kids just to get their turn, he used to get an attitude because he wanted to still play and make touchdowns. He was a little selfish. They’d pull him out after he made like four touchdowns and they’d say, ‘OK, you got your glory. Sit down and let another kid in.’ He didn’t like that one bit.

“Sometimes he’d just pout and cry.”

Not surprisingly, Lattimore was moved up to varsity as a freshman in high school. But, with older kids in front of him, he didn’t get a chance to play right away. He talked about quitting the team. His mom made him stick with it, though, and eventually he started to get playing time.

“Mom,” he said, “you have to promise me you’ll come to every game.”

Killebrew hasn’t broken that promise. She even got on a plane for the first time in her life to see her son play in a high school all-star game in Texas. Her second flight was to Philadelphia to see the draft in person.

“Because of him, I finally left Cleveland,” she said with a laugh. “Football has its perks.”

There’s no denying Solomon Thomas is a big man. But at 6 feet 3 and 273 pounds, the former Stanford defensive end isn’t massive by NFL standards.

As a kid, he was a giant.

“Solomon was 195 pounds in fourth grade,” said Martha Thomas, who was at her son’s side when he was selected third overall by the San Francisco 49ers. “He was bigger than the principal. His knees didn’t fit under the desks at school.”

That led to some difficulties.

“People talked to him like he was an adult and expected more of him,” she said. “They expected him to be good at things he wasn’t good at. He grew really quickly.”

Seven weeks premature, Thomas was four pounds at birth. He grew quickly, though, and was far bigger than his fellow preschoolers. The disparity widened as the years passed.

“He was in trouble a lot in elementary school,” his mother recalled. “He just knocked people over. He didn’t mean to. There was a lot of time on a bench at recess.”

More than once, Martha got called down to that grade school in Coppell, Texas. Now, whenever he drives people past that recess yard, Thomas proudly points to “my bench.”

As for mother and son, it’s almost like they have a psychic connection. That’s the way it feels for Martha when she’s watching a game in the stands, at least.

“It’s much harder to watch a football game when he’s playing,” she said. “I enjoy games a lot more when he’s not playing. Because I watch him, and I watch for his steps. I watch for his hand work. I watch how his technique is. So it is sometimes painful to watch him. I think, ‘Oh, he’s going to be mad about that,’ or, ‘He’s going to be happy with that play.’

“There’s been times where I’m like, ‘He’s going to get the quarterback. He’s mad.’ And he does. It’s almost guaranteed. You see a certain anger or whatever in their movements and you’re like, ‘Yep, he’s got this one.’”

That big kid on the playground finally got control of his body.

“I think he wanted to figure out some way to actually use his body to benefit himself instead of always getting himself in trouble,” she said. “Football worked out really well for that.”

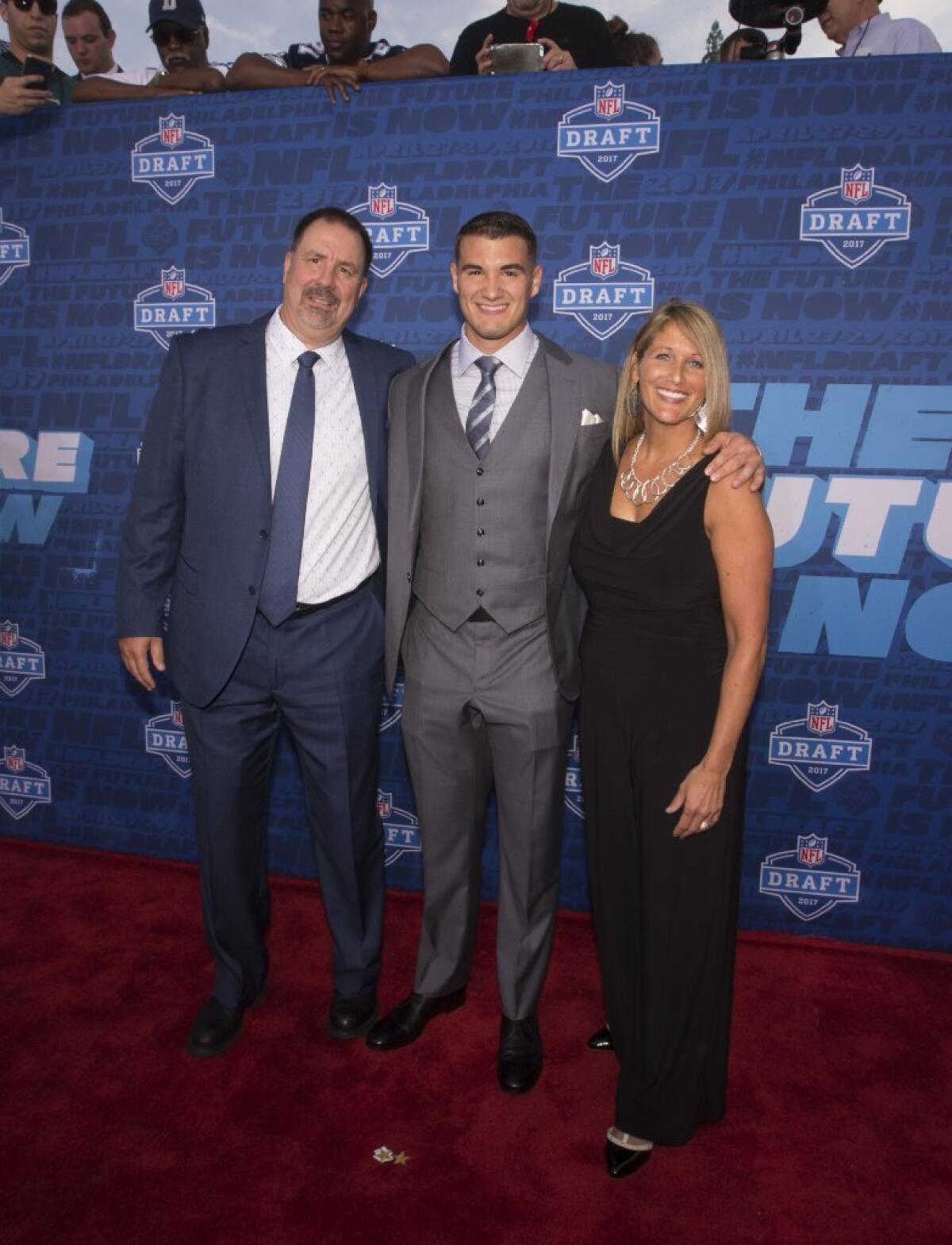

North Carolina quarterback Mitchell Trubisky was on the receiving end of one of those huge hits from Thomas. It came in the Sun Bowl in December, when Stanford edged the Tar Heels, 25-23.

Trubisky more than survived. The Chicago Bears paid three draft picks to move up one spot and select him with the No. 2 pick.

But his mom, Jeanne, won’t soon forget that hit.

“When Solomon Thomas sacked my son, trust me, I felt it,” she said. “But that doesn’t bother me. I know that’s their job when they go out there. That’s part of football. It’s part of being a mom. You have to get used to your child being hit or being the hitter. That’s just part of the stuff on the field. I respect Solomon. He was doing his job.”

That sense of peace didn’t come overnight. It took years, especially for a mother who describes herself as excitable.

“When he was younger and I was watching him play football, I used to watch him all the time,” she said. “But now that he’s older, I look down the field. I look for his receivers, I look to see if he’s missing anybody on any of his routes and stuff like that. It’s changed a little bit through the years. It’s evolved for me.

“There’s more than one kid on the field, and his job is to try to get the ball to the other person. So I do try to work on that a little bit.”

Mindy Kizer hasn’t quite gotten to the point where she can take her eyes off her son. Notre Dame quarterback DeShone Kizer, drafted by Cleveland in the second round, played on a home field where there was no video board. So he completed lots of passes during his career that his mom never truly saw until she returned home to Toledo, Ohio, to watch the game on DVR.

“When you first go to Notre Dame and you’re watching your son play, you want to see if the pass is complete or where the pass is going,” she said. “But you also want to keep your eyes on your kid. Is he getting knocked on his butt after the play is made? So it’s hard because you have to choose what you’re going to watch because you’re not going to see it again.

“My eyes tend to stay on my kid. You want to make sure that he gets up from the play. Sometimes you have to ask, `Did he catch it? What happened?’ But my eyes are fixed on him.”

It’s only natural, a mother looking out for her son. Mindy finds herself doing the same in public or on social media, although she has had to dial that down too.

“I’m told every single day, ‘Do not read social media.’ So what do I do five times a day? I read social media,” she said. “And then you just have to block it out. I respond to the messages. I’ll respond, I’ll put it on paper, I’ll tweet something, put it on Facebook, then wait five minutes and delete it all. So it makes you feel good.”

What makes it easier for Mindy is that DeShone is so good at shrugging off the criticism.

“It would be harder if he struggled with it,” she said. “I always said he’s mature beyond his years, kind of an old soul. Since he’s able to handle it, it’s easier for us to handle it. God put him on the earth for something bigger, and this is something.”

Mindy is a court bailiff in Toledo, and her husband, Derek, is a police officer. They don’t coddle their son, and he isn’t perfect.

“DeShone lost his wallet and lost everything in it,” his mother said. “It was the second time he lost it. I’m like, `Dude, I can’t just hand you money.’”

So, to earn back that money, Kizer had to come home and finish his parents’ deck.

“We don’t hand things over to him,” Mindy said. “He replaced his wallet and the money in it, but I got a new deck. Can’t be handed to you. You have to earn it.”

Late bloomer, early pick.

That pretty much describes Temple linebacker Haason Reddick, taken 13th overall by the Arizona Cardinals. This is a player who walked on to his college team and earned a scholarship only last season. He was all but ignored coming out of high school in the Philadelphia area, because a knee injury cut short his senior season after four games.

He had to have an operation to clean out the torn meniscus in his knee, and his mother, RaeLakia, was at his bedside when he woke up in the recovery room.

“The doctors weren’t in the room,” she recalled. “So I’m sitting there, and he asked, ‘What did they do?’ I told him they were able to go in and repair it. And immediately he started to cry because he knew he wouldn’t be able to play for the rest of the season. It was very hard to watch. I felt helpless and all I could do was just be there and support him the best way I knew how. Just be a mother.”

Early on, RaeLakia knew her son had something special.

“He’s always been good, even in pee-wee,” she said. “I could be biased, but he’s always been a good player. I can’t even remember who they were playing, but the very first time he got to play on a field and get a sack, I was like, ‘Whoa. This kid’s a beast.’ I was like, ‘Yeah, son!’ I thought, ‘He’s powerful. He’s got it.’”

But a mother worries about her son. On every play. Beast or not.

“I watch him the whole time,” she said. “As a mom, your biggest fear is the physical part of what could come with that play or that tackle or that sack. I don’t even know if it’s even possible, but before every game he would play in college, I’d just text him and say, ‘Play smart. Play hard, but play smart and play safe.’ Whether that’s even possible or not, I don’t know. But I just wanted to send him out there with that.”

And she thinks about the long-term effects of football. She has heard the stories, frets about head injuries and memory loss. This is her child.

“It’s very scary,” she said. “I was actually hesitant to watch ‘Concussion.’ I just didn’t want to, but I did. It actually informed me a little more on what could happen. I know things have changed, and things are a lot safer. I just pray that he’s OK and has longevity in the NFL.”

Being selected in a draft that took place a mere 15-minute drive from his childhood home? That was a good start for Reddick.

“This location, this event, this moment, this time, it was meant to be,” RaeLakia said. “This was not a coincidence. This was meant to be.”

Moms. They always know what to say.

Follow Sam Farmer on Twitter @LATimesFarmer

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.