Column:: As the Pyeongchang Olympics closes, so too does the myth of fair competition

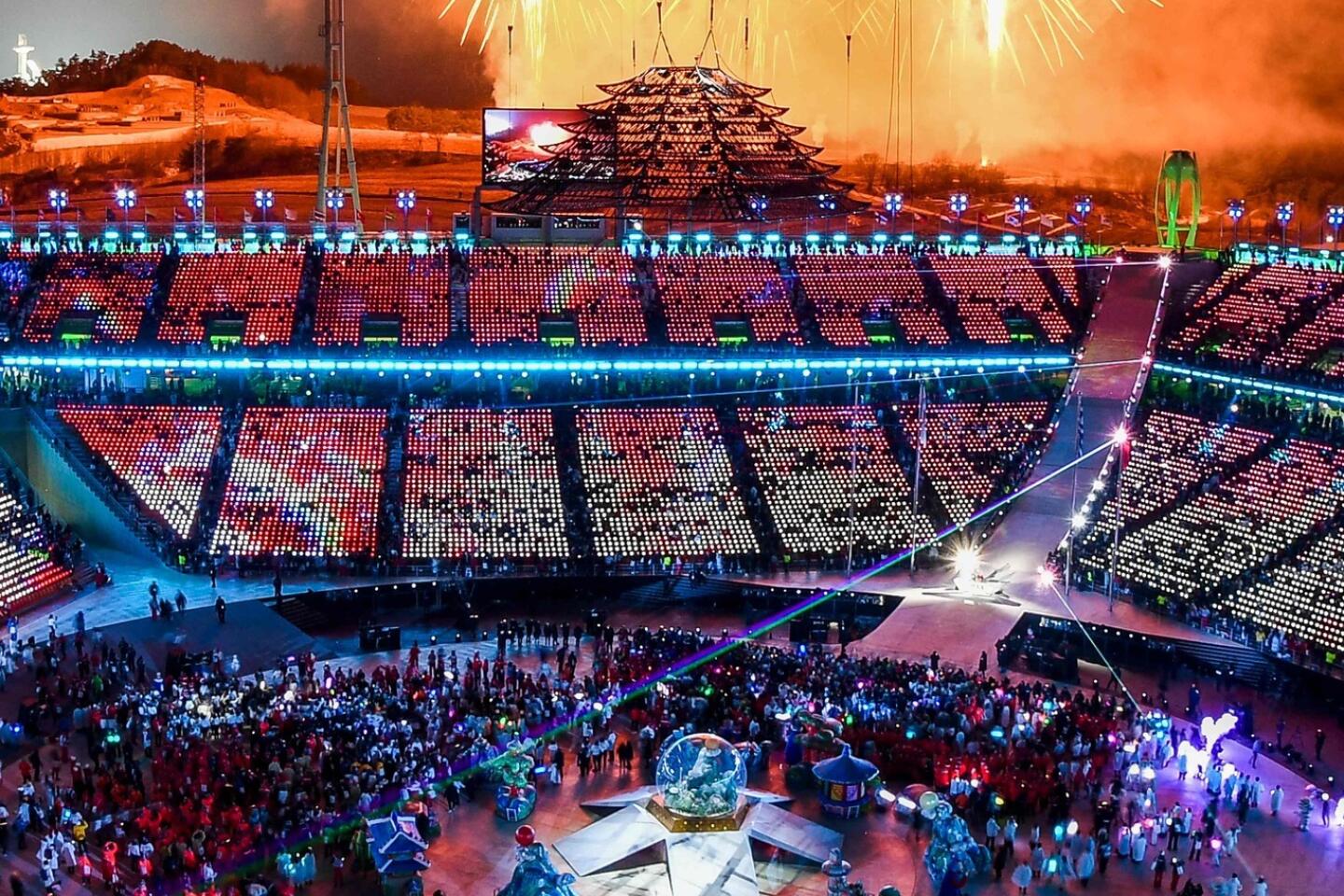

Reporting from PYEONGCHANG, South Korea — Representing the union of the world’s continents, the interlocking rings on the Olympic flag symbolized something else Sunday night at the closing ceremony of the Pyeongchang Games.

Frustration. Exasperation. Hopelessness.

So much for Faster, Higher, Stronger.

With the International Olympic Committee refusing to reinstate Russia for the ceremony, the five-ring banner remained the adopted flag of the country’s delegation, which competed under the moniker of Olympic Athletes From Russia.

The neutral flag was ushered into the Pyeongchang Olympic Stadium along with those of the other participating countries. It was raised during a medal ceremony for the men’s 50-kilometer cross country ski competition, one on each side of Finland’s flag, as Alexander Bolshunov and Andrey Larkov finished second and third, respectively, to Iivo Niskanen.

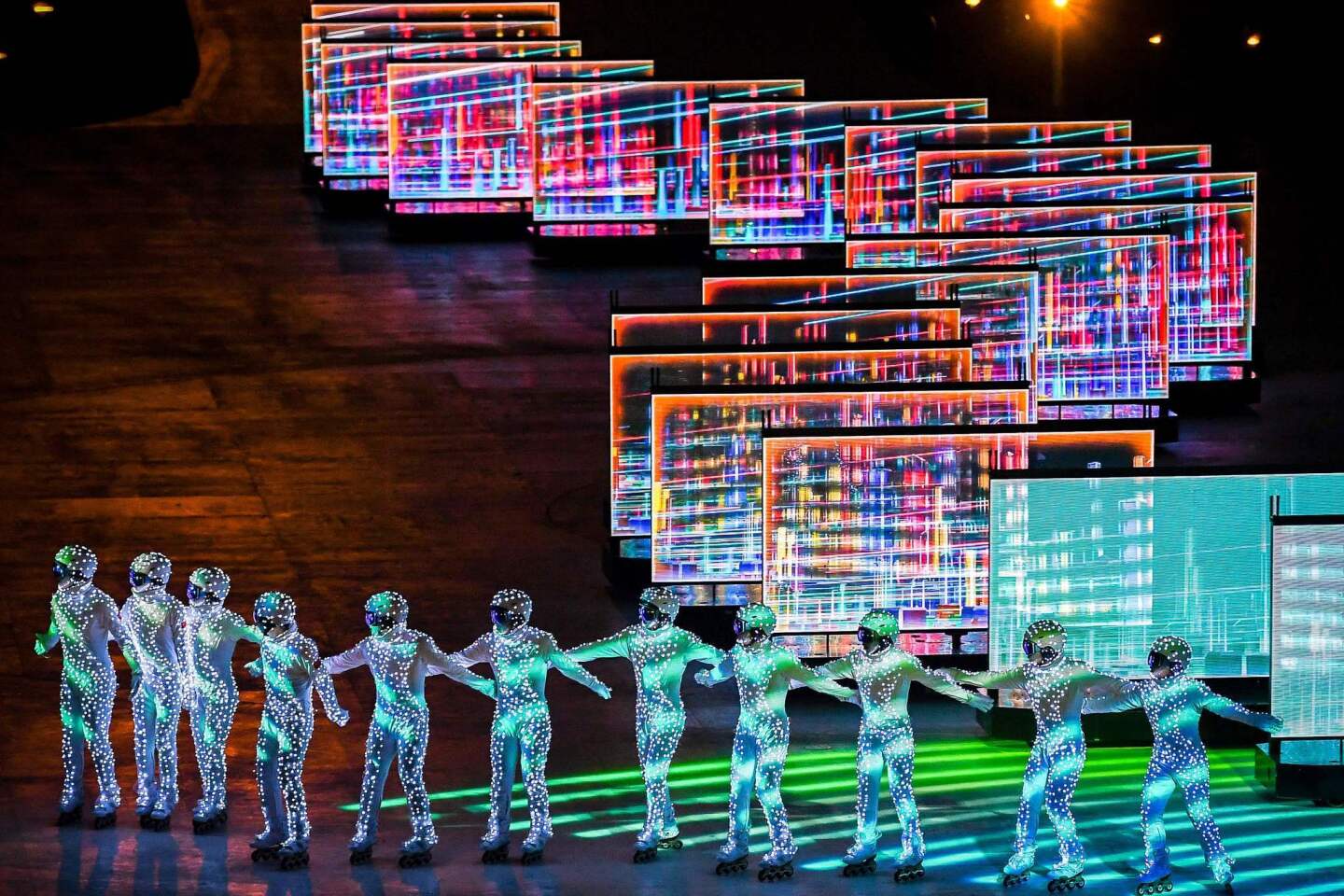

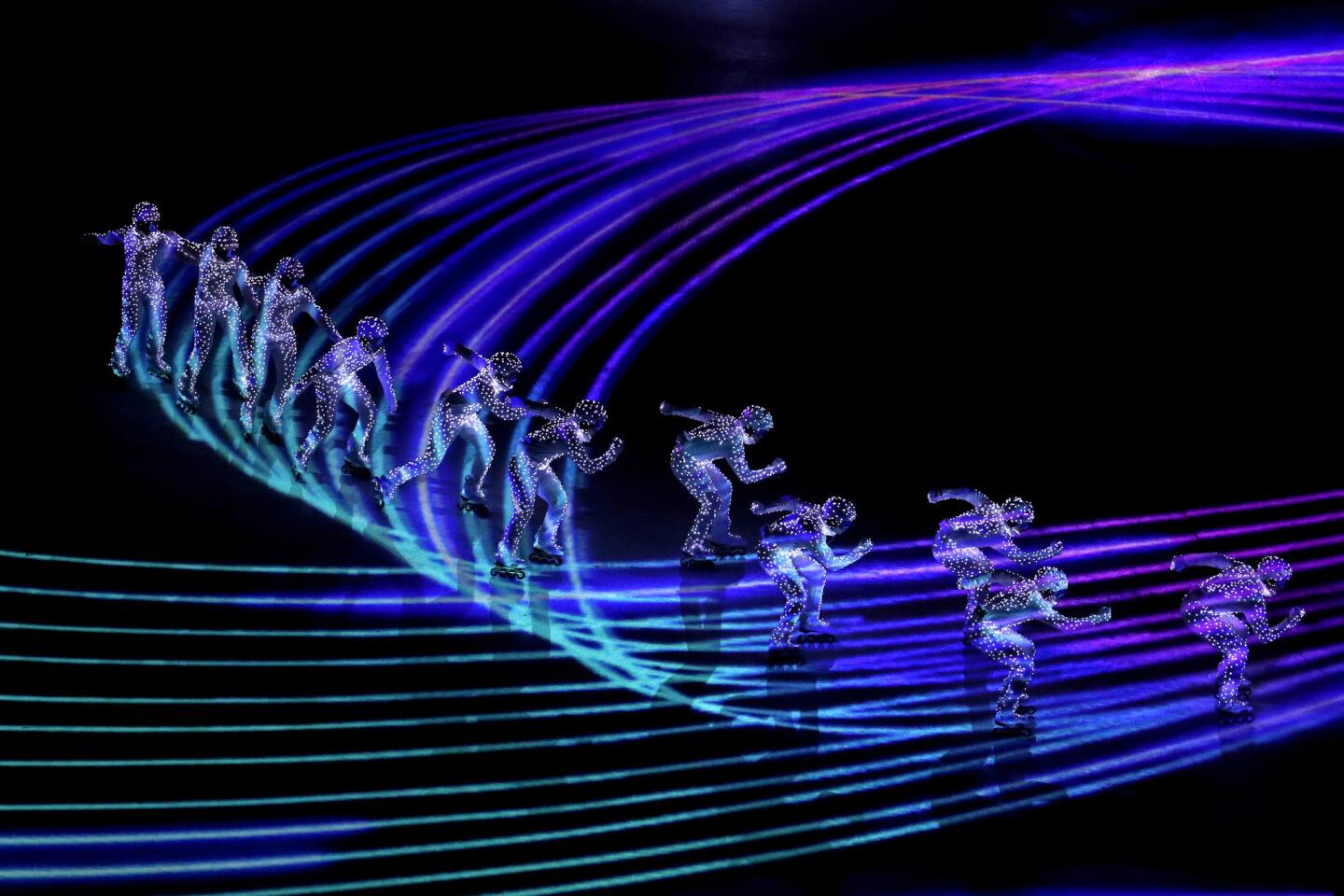

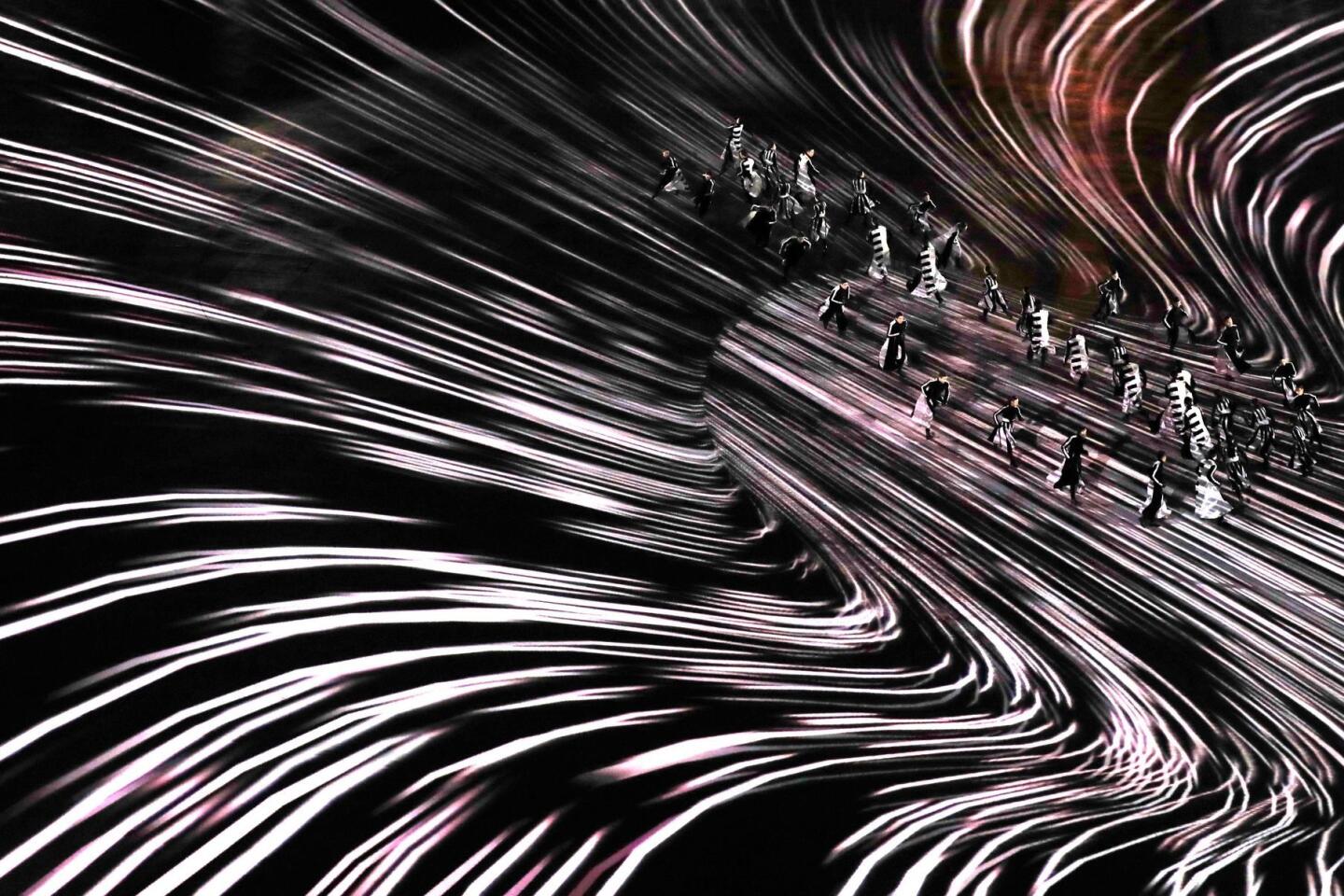

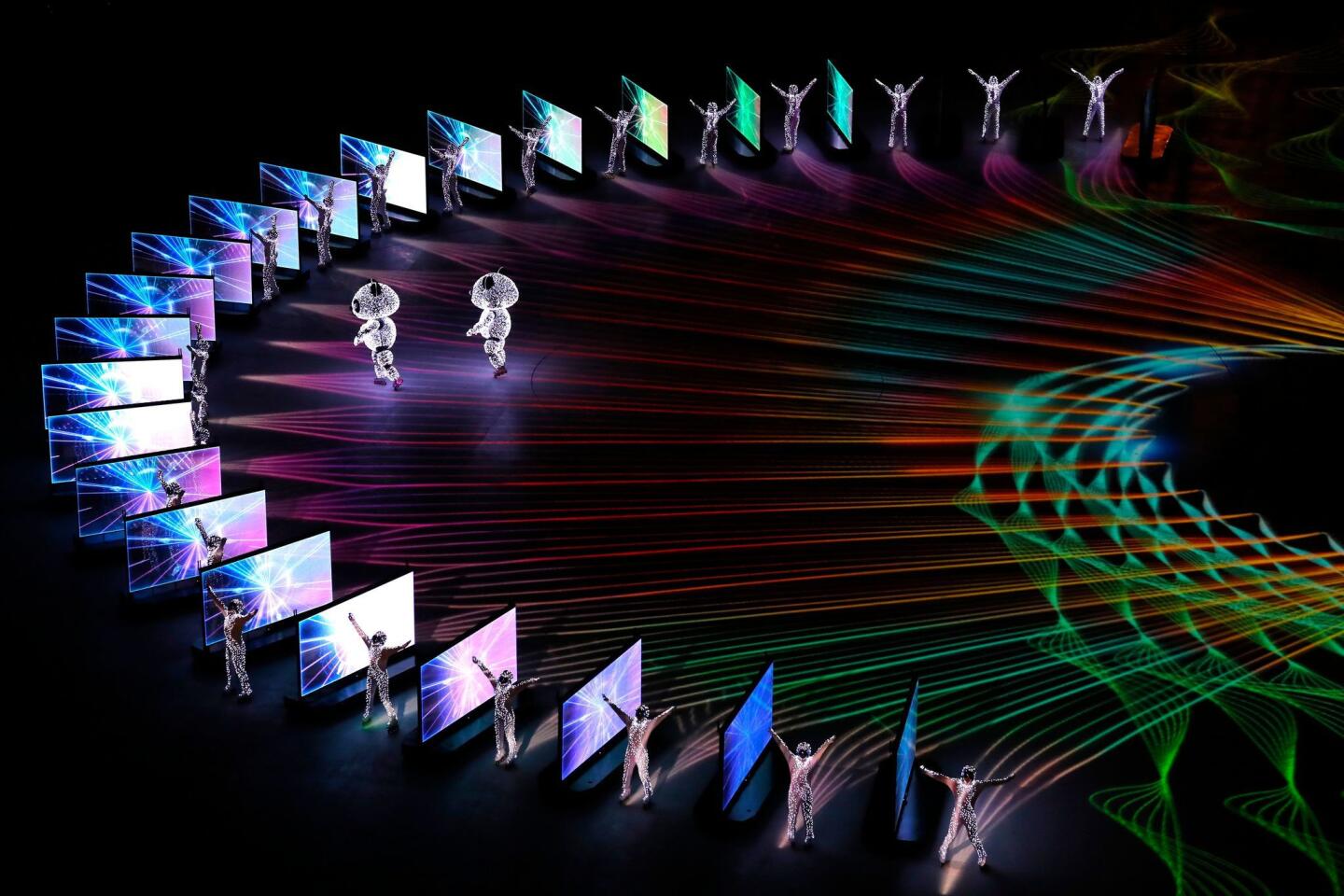

These awkward moments are what will be remembered about this closing ceremony, not the K-pop performances, messages of hope and solidarity or extravagant fireworks displays.

Russia will be reinstated by the IOC in the coming weeks or months, provided no more of the country’s Winter Games participants test positive for banned substances. But the underlining tensions will remain.

The IOC was in a no-win situation.

Considering the scope of Russia’s state-sanctioned doping program and the damage it inflicted on the 2014 Sochi Games, the country’s Olympic committee deserved worse. The ban wasn’t a complete ban, as the 168 athletes from Russia were allowed to compete in Pyeongchang as neutral OAR athletes. Restoring Russia’s status as a participant for the 2020 Tokyo Summer Games feels like letting a fox back into a henhouse in which he already has feasted, especially with the Russian Anti-Doping Agency still suspended by the World Anti-Doping Agency.

On the other hand, complete or continued banishment of Russia would have punished individual athletes who had no control or say over the government-backed drug program. Compared to other athletes, the Russians were subjected to more extensive drug screenings before and during the Games.

There were four positive drug tests at these Olympics, two of them by OAR athletes. But IOC President Thomas Bach explained that he didn’t view the cases as extensions of what Russia did in Sochi. These were isolated instances, he said, as opposed to part of systemic abuse.

Bach said he was pleased with how OAR responded to the positive tests, particularly that of bronze-medal-winning mixed curler Alexander Krushelnitzky. OAR didn’t appeal the results of the test and immediately returned the medals that were won by Krushelnitzky and his wife.

However, the two positive tests were why Russia failed in its quest to be reinstated for the closing ceremony. Bach never explained why. Bach also never said how the IOC determined these were isolated cases instead of part of something larger.

“This fight with doping will never be over,” Bach said. “We have to be realistic. The day where we say ‘We have won this fight against doping’ will not come. As long as you have human beings in competition with each other, you will have some who try to cheat. In society, you have laws against theft or robbery for thousands of years, but there is still theft and robbery. This is unfortunate, but we cannot ignore human reality.”

Bach’s statement was common sense. It was also extraordinary.

As much as anything, the organizations and leagues that control sports sell stories — stories about athletes, stories about the significance of competitions, stories about what the sports themselves represent.

To be in the sports-entertainment industry is to nurture and protect these myths.

By saying what he did, Bach conceded one of the great myths of the Olympics — the one about a level playing field — is, in fact, a myth.

If the Olympic ideals exist, they exist inside of the athletes.

When a group of American athletes was asked about the IOC’s decision on Russia, a United States Olympic Committee spokesman answered for them.

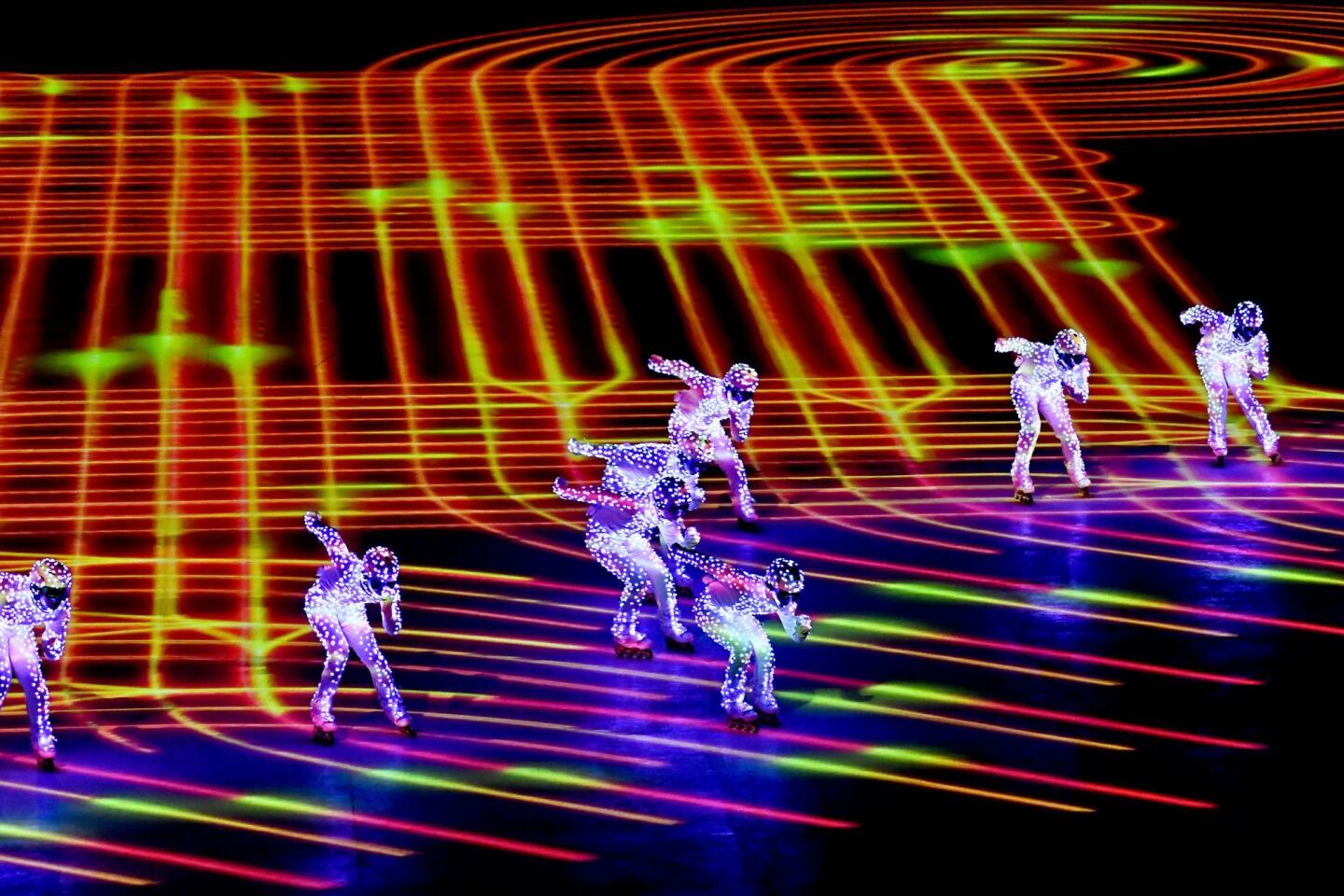

Team USA athletes take part in the closing ceremony of the Pyeongchang 2018 Winter Olympic Games.

“You’re telling us the news, so I think we probably need a little time to digest it,” he said. “But it seems like the appropriate decision.”

But freestyle skier David Wise spoke up.

“Cheating’s cheating,” Wise said. “I think any true competitor, any true champion, admires winning fairly more than winning in general. And some people get lost in that and they make winning their end goal rather than winning well and winning with a conscience, so, yeah, cheating’s cheating.”

Bobsledder Elana Meyers Taylor added to the chorus of frustration. She spoke of how drugs specifically have affected her sport. OAR’s other positive test at these Games was by a bobsledder.

“It’s a really difficult situation as an athlete to know that these offenses have occurred and that they’ve drastically affected medals, and not only medals, but even who was able to participate in the Games,” Meyers Taylor said.

Meyers Taylor understands why this is a problem not only for her sport, but the entire Olympic movement.

“I feel like there’s been a loss in faith of the athletes of these Games, of all Games, because of the offenses that have occurred,” she said.

She still believes. But who else does? And if there are others, for how much longer?

Twitter: @dylanohernandez

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.