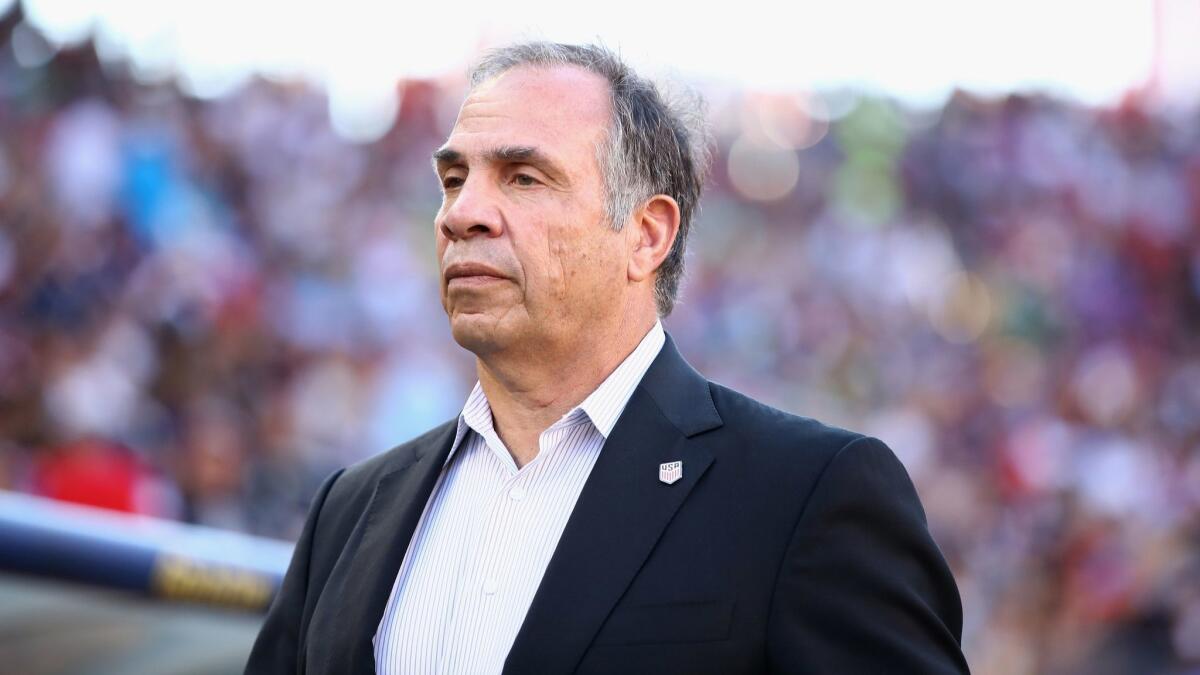

After U.S. team misses qualifying for World Cup, ex-coach Bruce Arena writes about state of U.S. soccer

When Bruce Arena was asked to rescue a struggling U.S. national team in the fall of 2016, he was also asked to write a book about how he did it.

He said yes to both requests. Neither one worked out quite the way he had hoped.

“The book,” Arena said, “was going to be that we qualified for the World Cup and getting ready for the World Cup.”

Spoiler alert: The U.S. didn’t make it that far, a stunning 2-1 loss to Trinidad and Tobago in the final match of the 10-game qualifying tournament in October stopping it short of the tournament for the first time in 32 years. It also led to Arena’s resignation as coach three days later.

“There’s absolutely no excuses,” he said then and repeats now.

But on the bright side that failure produced a far more important book. Because rather than walking the triumphant path to Russia, Arena instead confronts many of the issues facing U.S. Soccer and warns that, without serious and substantial change, this may not be the last time the Americans miss a World Cup.

Full coverage: 2018 World Cup »

“They just don’t get it, the people that run the sport in our country. And U.S. Soccer has a major obligation to get it right,” Arena said in a phone interview. “There needs to be a change in leadership.”

The book, “What’s Wrong With Us: A Coach’s Blunt Take on the State of American Soccer After a Lifetime on the Touchline,” written with journalist Steve Kettmann, is scheduled for release June 12, two days before the first U.S.-less World Cup opener since 1986.

The issues Arena identifies were present when qualifying started and likely would have been swept under the rug had the U.S. succeeded in making it to Russia. The fact it didn’t has led a lot of people to ask why.

Arena has some answers.

One problem, he writes, starts with the fact the top ranks of soccer in the U.S. are too insular, with the same people talking to one another rather than seeking fresh ideas and perspectives from outside.

There is also a huge void in leadership, specifically on the technical side with the two largest professional soccer bodies in the country, U.S. Soccer and MLS, run by people Arena says have limited technical knowledge of the sport.

And while those two groups have made the game financially and commercially successful — U.S. Soccer alone reported revenues of $152 million in 2017 — that has not made up for a lack of vision.

“It’s not like you’ve got to have a clean sweep of everything and make all radical changes,” he said. “You just need the right leadership with the right ideas and get going.”

February’s election to replace Sunil Gulati as president of U.S. Soccer may bring only incremental progress since the winner, Carlos Cordeiro, last played soccer in high school and has spent much of his adult life on Wall Street. The top three men in MLS — commissioner Don Garber, deputy commissioner Mark Abbott and senior vice president Todd Durbin — have backgrounds in marketing and the law, not soccer.

But if there’s a lack of vision and technical experience, there’s no lack of talent. More kids are involved with the game in this country than ever before; according to one estimate, more than 17 million people over age 6 are playing soccer in the U.S., more than twice as many as in Germany and England combined.

Ironically, they’re finding less opportunity to do so in MLS, a league created, in part, to develop U.S. players.

Less than 46% of the players on this year’s opening-day rosters were born in the U.S., compared with 16% from the league’s first season in 1996. And while the overall number of Americans is up from 1996, thanks to expansion that has more than doubled the number of MLS teams, the meaningful minutes those men will play is way down, with just a third of the starters on the 12 teams that made the playoffs last season even eligible to play for the U.S. national team.

When Mexico became concerned a decline in playing time for homegrown talent in its domestic league could impact the national team, it passed a rule requiring a minimum number of minutes for young players and another requiring a quota on Mexican players in each match-day squad.

MLS has gone the other way, giving more jobs and more minutes to foreign-born players. That’s a trend U.S. Soccer, the governing body for the sport in the country, needs to correct, Arena said.

Despite all that, Arena believes the soccer potential in the U.S. remains great. Without meaningful reform, though, it will continue spinning its wheels.

“If we don’t make changes,” he said, “we’re not going anywhere.”

It’s a wake-up call that demands attention since it comes from the most successful coach in both MLS and U.S. Soccer history, a man who took the national team to its highest height – the World Cup quarterfinals in 2002 — and its lowest low — the qualifying failure in 2017. Yet it’s an examination that may have been delayed at least a year had another revelation in Arena’s book come to pass.

U.S. Soccer planned to fire Juergen Klinsmann as coach and replace him with Arena in April 2016, the coach writes, months before the start of the final phase of World Cup qualifying. On the day contract details were to be ironed out, Dan Flynn, U.S. Soccer’s chief executive, was rushed to the hospital for heart-transplant surgery and the negotiations never took place.

“It was a done deal until Dan left,” said Arena, who finished the MLS season with the Galaxy while Klinsmann remained coach of the U.S. team.

When the Americans lost their first two qualifiers, however, Arena was brought on board when the team was in a 0-2 hole with eight games remaining, a deficit it never fully made up.

“In all honesty,” Arena said, “I think if I had come in in April, it would’ve been a heck of a lot easier for us to qualify for a World Cup.”

Maybe. But the book wouldn’t have been as good.

kevin.baxter@latimes.com | Twitter: @kbaxter11