Dorados de Sinaloa have given purpose to Diego Maradona’s upstream fight to sobriety

- Share via

When he was the world’s greatest soccer player Diego Maradona moved with the grace and speed of a jungle cat. Now he shuffles slowly across the lobby of the hotel he calls home, the sandals on his feet never leaving the tiled floor.

He has been asked to walk over and say hello to a group of well-coiffed women who are having breakfast. As he painfully makes his way into the dining room, an aluminum cane provides support for knees ravaged by advanced osteoarthritis.

These mornings, they’re the worst.

Maradona offers the women weak handshakes, but he brightens when given attention and poses for selfies. Days shy of his 58th birthday, he could pass for decades older. The flowing black locks that once framed a cherubic face are graying and cut short, leaving a slightly bloated appearance. His speech, formerly playful and confident, is a labored, unintelligible whisper.

“He mumbles,” a woman says in Spanish as she leaves the breakfast, imitating Maradona by softly speaking as if she were gargling rocks. She then rubs an index finger beneath her nose, a well-known pantomime for snorting cocaine.

“He’s already a little out of it,” she huffs dismissively.

What Maradona did on the field cost him his knees, which doctors say must be replaced with prosthetics. What he did off it, well-documented decades of drug and alcohol abuse, nearly cost him everything else. While Maradona professes to be clean, the reputation of his hard-living past hangs over him like a dark cloud.

Since coming here two months ago to coach a second-division soccer team, Maradona has inspired countless reactions, from respect and worship to pity and scorn – often at the same time, as with the women who gleefully took pictures with him, then mocked him after he left.

It’s a split persona — hero and villain — Maradona has embodied most of his life. The conflicting images are well understood in Culiacan, where thieves and drug traffickers are often portrayed as the good guys and a troubled former soccer god can be welcomed as a savior.

The city’s soccer team was winless and buried deep in Mexico’s second-division Liga de Ascenso when the new coach took over in September. With Maradona, the Dorados of Sinaloa won five in a row and had already clinched a playoff berth heading into Saturday’s regular-season finale with Atletico San Luis.

In their first six league games under the old coach, former Chivas manager Francisco Gamez, the Dorados scored a total of two goals. They have averaged nearly that many in seven games under Maradona.

“He’s very passionate. Since he’s come you’ve seen a tremendous change in our attitude, our work, our dedication and our soccer,” Colombian forward Juan Galindrez says in Spanish. “He’s an historic figure. Working with Maradona has been the best thing that’s happened to me in my soccer career.”

Exactly how the coach feels isn’t easily discernible.

Maradona turns down most interview questions, limiting media access to post-game news conferences where his mumbles are indecipherable. Grupo Caliente, which owns a majority interest in the team, isn’t much help, either. It declined requests for comment to be used in this article, instead trotting out some of the team’s youngest players to deliver what seem like scripted messages.

“I see him as someone good,” said Angel Uribe, a teenage defender from San Diego, stating what quickly became a familiar party line. “I don’t even care about his past. I see him kind of like my teacher.”

Friends say coming to Culiacan has given Maradona renewed purpose — a reason to get up in the morning and, more importantly, to go to bed rather than to a bar at night. His partying days, he has promised, are over.

“Emotionally I feel that I’m in the best moment of my life,” he told reporters when he took the job. “I want to give Dorados what I lost when I was sick. … I want to see the sun and I want to go to sleep at night.”

Fox Deportes analyst Daniel Brailovsky says Maradona is “very happy, very satisfied with his work.”

“It’s his passion, it’s his life,” his former teammate adds. “It’s everything for him.

“Maradona can’t live without football. And football can’t live without Maradona.”

For years, Maradona was soccer’s loud, uncouth uncle who was never invited to family gatherings but often showed up anyway, ruining the event for everyone else.

He was suspended by FIFA in 1991 after testing positive for cocaine. Three years later, he was thrown out of his last World Cup after failing another drug test — though not before celebrating his 34th and final international goal by running at a sideline cameraman with wild, bulging eyes and a distorted face, a frightening image beamed to millions of television sets around the world.

Those young players never saw him play but they’ve seen the videos. And when Maradona talks, it has the power of authority.

— Fox Deportes analyst Daniel Brailovsky

He has fired an air rifle at reporters. He was charged by Italian authorities with skipping out on nearly $42 million in unpaid taxes. And, just last summer, his bizarre behavior at the World Cup in Russia included a widely photographed moment in which he made obscene gestures with both hands to celebrate a goal and another in which he pulled his eyes into slants while looking in the direction of South Korean fans. He also appeared inebriated in a video.

Even when he did good he did bad, as in 2010 when he coached Argentina to the World Cup quarterfinals while enduring criticism for diva-like demands that his South African suite undergo thousands of dollars of renovations to add expensive toilets and bidets.

Still, his missteps haven’t erased memories of Maradona’s unparalleled brilliance on the field, which command respect from players born long after his prime.

“He really likes working with young players,” Brailovsky said. “If it’s Maradona talking the message is much stronger, much more profound. Those young players never saw him play but they’ve seen the videos. And when Maradona talks, it has the power of authority.”

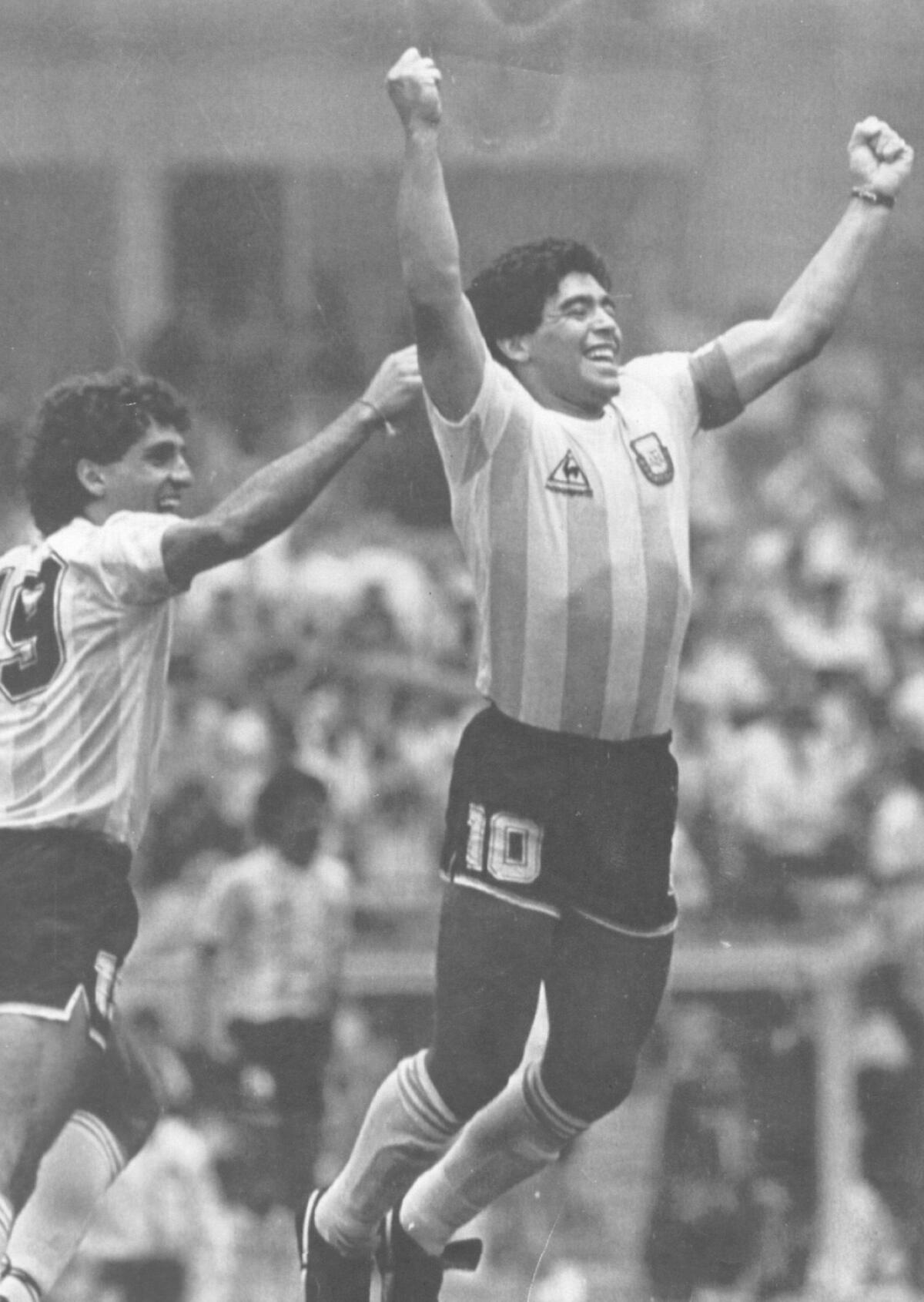

The two goals that defined his career and established that authority came five minutes apart in Mexico City’s Azteca Stadium, during a 1986 World Cup quarterfinal win over England.

Maradona clearly used his hand to punch in the first, but because there was no instant replay the score stood. Later, Maradona cheekily insisted the ball was redirected “a little with the head of Maradona and a little with the hand of God.”

The second goal was pure genius, and perhaps the greatest in World Cup history. After receiving the ball in his own end, he dribbled more than half the length of the field at a full sprint, eluding five defenders and then so thoroughly confusing the goalkeeper that the poor guy fell to the turf, leaving Maradona to score the game-winning goal into an empty net.

Seven days later, Argentina won its second World Cup title and Maradona was voted the tournament’s best player.

The mastery of the second goal and the mischief of the first inspired the French newspaper L’Equipe to dub Maradona, then 25, “half angel, half devil,” locking in a reputation that still defines him.

“He is someone many people want to emulate, a controversial figure, loved, hated, who stirs great upheaval, especially in Argentina,” Jorge Valdano, another former teammate, once observed. “Maradona has no peers inside the pitch, but he has turned his life into a show.”

More than 20 years after his last game, Maradona is still worshiped in Argentina, where he is frequently referred to as D10S, a combination of his uniform number and the Spanish word for God.

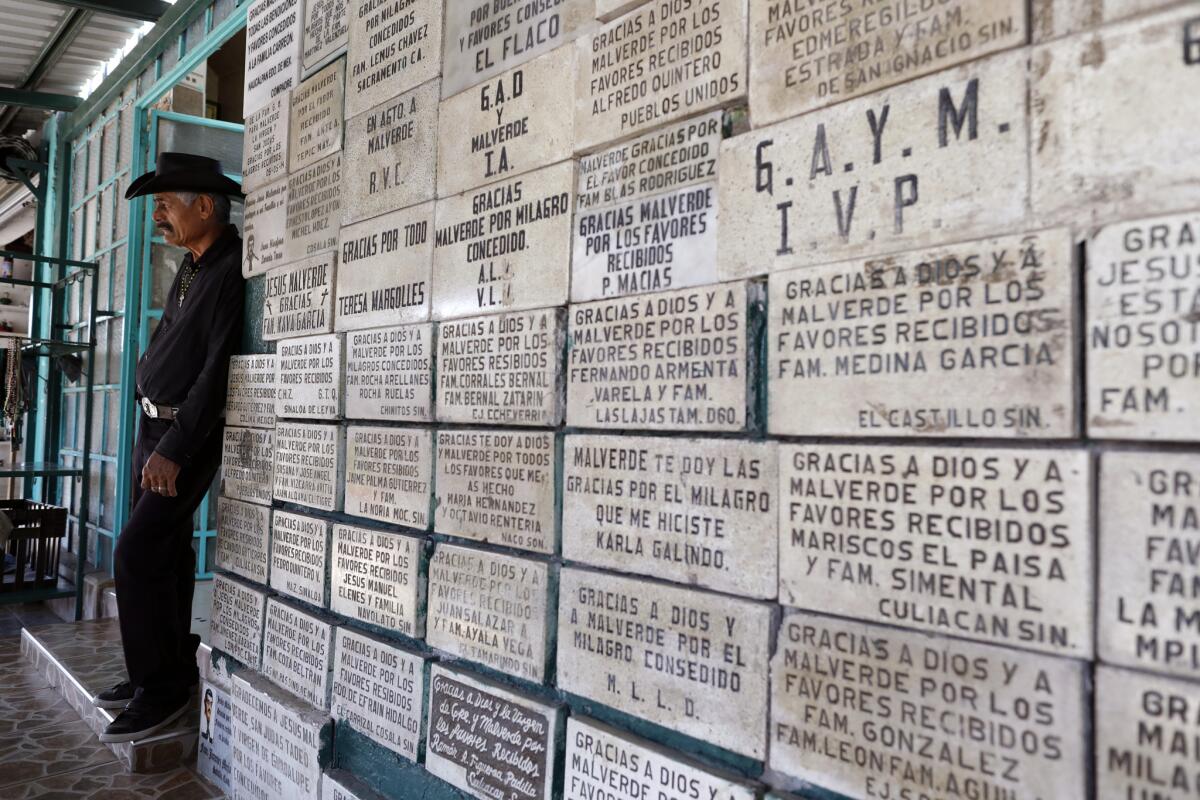

“He was touched by God to play soccer the way he played. For him it was always easy,” says Galindrez, who is also aware of his coach’s less-divine side. Nowhere outside Maradona’s homeland is that duality better understood than in Culiacan, which has a rich history with its own sinner-saint: Jesus Malverde, a man known variously as a generous bandit, an angel of the poor and, now, as the patron saint of narcotics traffickers.

According to local folklore, Malverde grew up in rural Culiacan, where peasants were abused by greedy landowners. When his parents died as a result of their poverty, the “Robin Hood bandit” avenged their death by raiding the haciendas of the wealthy to provide for the poor.

In recent times, Malverde’s example has been appropriated by Sinaloa’s deadly drug cartels, who funnel some of their drug profits into schools, road repairs and community projects.

“Malverde and those associated with cartels are viewed as fierce defenders of a way of life different than that of cosmopolitan Mexico City. Part of that identity is rooted in a ‘tough guy with a kind heart persona,’ ” says Christopher E. Lomelin, a doctoral student in religion at the University of Florida who has studied Malverde. “Maradona fits this bill. He meshes well with local culture, as many in the region seem to like rooting for the tough guy with a kind heart.”

Maradona’s background isn’t all that different than the one ascribed to Malverde. He grew up in a shantytown on the southern edge of Buenos Aires, where he was spotted by a soccer scout at the age of 8. Eventually, he made millions but he never forgot his humbling beginnings, raising stacks of money for children’s charities around the world.

Shortly after arriving in Culiacan, he endeared himself to the city by staging a $175-a-plate dinner to raise money for victims of Hurricane Willa.

“They’re very similar,” Luis Valdez, a Dorados fan clad in the team’s honey-mustard-colored jersey, says of Malverde and Maradona. “Malverde here, they love him. It’s the same with Maradona.”

Maradona’s presence has arguably made Sinaloa the most-famous second-division club in the world. After his first game as coach this fall, opposing players surrounded Maradona in the stadium tunnel, asking for autographs and posing for selfies. And for the Dorados’ second-to-last home game of the regular season a team spokesman said about 100 media credentials had been issued.

Outside Estadio Banorte, the Dorados’ weathered concrete stadium on the western banks of the Humaya River, the team bus pulls up near the tunnel leading to the locker room.

Maradona, among the first off the bus, nods and smiles toward a small crowd of fans, who call to him through a chain-link fence.

“This guy demonstrated on the field he was the best player,” Luis Borrego says between draws from his beer. “And here he is teaching these kids how to win.”

As Maradona, leaning heavily on his cane, slowly shuffles toward his team’s midfield dugout, some fans push against the white railing separating the stands from the field. One boy holds a home-made poster of Maradona with a dozen pictures but just one word: “Dios” — God — it reads.

The coach collapses into a seat at the far end of the bench just before kickoff, but as the game progresses he grows more animated. In the 14th minute, he comes out into the technical area to argue a call. A minute later, he raises his arms to celebrate a game-tying goal from Vinicio Angulo, the player who wears the number 10 Maradona made famous.

By the time the final whistle sounds, Maradona has ditched the cane. As he makes his way onto the field to high-five each player he is moving normally, the slow, painful shuffle from the hotel miraculously cured.

“He gets excited and he forgets about his injury. It’s weird,” says Fernando Arce, whose goal just before halftime proved the winner.

Adds Uribe: “Before the games he looks like he’s hurting, like he can’t walk. But after the wins, he’s dancing.”

Before the games he looks like he’s hurting, like he can’t walk. But after the wins, he’s dancing.

— Angel Uribe

How long the dance will last is unclear. The famously fickle Maradona has coached four other club teams, and only once did he last as long as 20 games. Just four months before taking the $150,000-a-month job in Culiacan — one that reportedly makes him the second-highest-paid coach in Mexico — he accepted a three-year contract to serve as president of Belarusian club Dinamo Brest.

Now, two months into his stint with Sinaloa, there is already talk of him moving to Tijuana and taking over that city’s struggling first-division club, which is also run by Grupo Caliente.

Maradona, his adrenaline exhausted, leans on his cane again as he limps into a post-game news conference to push back on that rumor, saying he wants to remain in Culiacan for the length of his three-year contract.

It’s all so taxing, and now it’s late.

The next morning is only hours away. And those mornings, they’re the worst.

kevin.baxter@latimes.com | Twitter: @kbaxter11