How COVID-19 could lead to opportunities and pitfalls for MLS TV coverage

Amy Rosenfeld doesn’t consider herself an artist. Yet in nearly three decades in television, she has helped bring some of the most memorable images in U.S. soccer history into tens of millions of American homes.

Brandi Chastain’s shirt-doffing celebration at the 1999 Women’s World Cup. Abby Wambach’s game-tying header in the final seconds of overtime in a 2011 Women’s World Cup quarterfinal. Landon Donovan’s game-winning goal against Algeria in stoppage time at the 2010 World Cup.

But never has she had the chance to work with the kind of blank canvas she has been given for the MLS Is Back tournament, which kicks off Wednesday at the sprawling ESPN Wide World of Sports complex in Orlando, Fla.

The result might be some of the most innovative soccer TV coverage in recent memory.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the five-week competition will be played without spectators — or grandstands — on a series of fields more commonly used for youth tournaments. For Rosenfeld, who has produced coverage for eight World Cups and five Olympics, it will be like doing a game from an empty prairie.

The possibilities — and potential pitfalls — are endless.

“It’s very depressing that there are no fans. But then how do you take a negative and make it a positive?” she asked. “Everything is going to be an experiment because everything is new territory. So what we’re trying to do is say, ‘OK, let’s see what that’s like.’ ”

MLS Is Back tournament could be in jeopardy due to players testing positive for COVID-19 and other clubs delaying their arrival to Orlando, Fla.

For the opener, at least, it will be like no other soccer broadcast in history. Rosenfeld and her 160-person crew plan to use more than 20 cameras, about double the number for a regular MLS broadcast. Two will be in the locker rooms, one on a drone that will buzz the field far lower than would be safe in a stadium with fans and two others on poles that will extend behind the goals.

The plan is to have the center referee wear a microphone while others will be embedded in the turf near the center circle and close to both benches. About the only thing you won’t see or hear is the sweat dripping from each player’s brow. But Rosenfeld is working on that.

“Our position is to be authentic to the experience,” she said. “Talk to me in three weeks and I may say, ‘Oh, that was a terrible idea.’ I personally am curious how this will sound.

“You’re going to hear cleat hitting ball. You’re going to hear when the goalie makes a save. Things that never get exposure because the crowd is drowning it out. My hope is it will feel immersive.”

The all-access experience isn’t cheap. Although ESPN and MLS, which is responsible for much of the upfront costs, declined to discuss figures, the production cost for the tournament will probably be about $10 million. Some of that money will go into health and safety measures given that the tournament is being played in the middle of a global pandemic.

“Eighty percent of my meetings have been about that and not about the number of cameras we’re going to use,” Rosenfeld said.

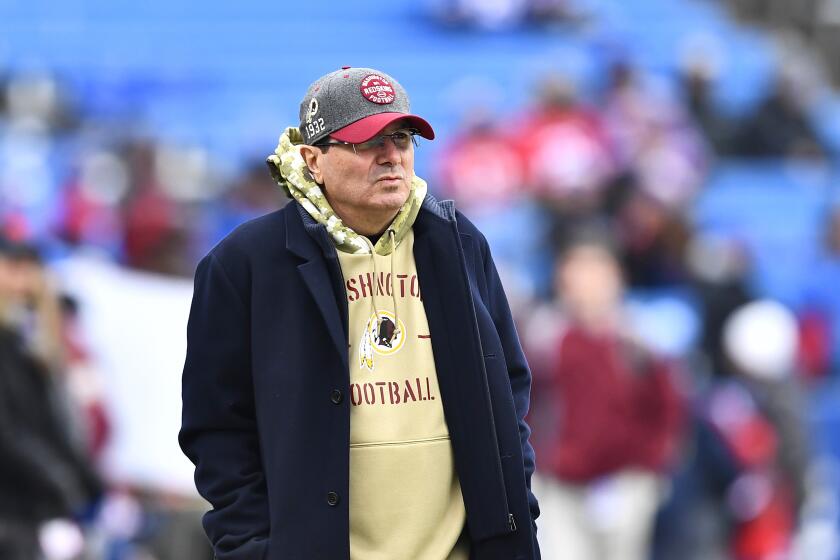

MLS Commissioner Don Garber, noting the tournament’s unusual setting, has likened the games to a “studio show” in which the sights and sounds can largely be controlled, just as they can on a Hollywood sound stage. And that’s allowed the league and its broadcast partners to push the envelope.

A scheduled game between FC Dallas and the Vancouver Whitecaps was postponed after six Dallas players and two Vancouver players tested positive for COVID-19.

“Our fans, when they see how the games are produced, will be impressed with the technology and the thought that’s gone into trying to test a handful of new concepts,” he said. “We’ll have more cameras. There will be more access to audio and ad views. And we’ll be able to utilize some technology that we’re experimenting with in these broadcasts.”

The most creative element will be one that no one at the games will be able to see. For viewers at home, one side of the field will appear to be an animated stadium with advertisements running along the edges while a virtual Jumbotron, also visible only on TV, will rise from behind both goals and occasionally at midfield. The technology is similar to what TV weathercasters use when they stand before a green screen and point to a map no one on the set can see.

“The virtual is going to be a pretty significant component of the broadcast,” said Rosenfeld, 53. “It gives the opportunity in some instances to handle sales and advertising because in a sense we’re creating what would have existed if we were in the stadium. But not all the cameras will have it.”

For Rosenfeld, an Emmy Award winner who will oversee production of all 54 games for ESPN as well as for MLS broadcast partners Fox, Univision and Canada’s TSN, there will be no fans or physical structures to work around, so camera angles can be set or manipulated at will. She has especially high hopes for the ESPN drone cameras that Rosenfeld hopes will give viewers a new perspective on the game and its players.

In the weeks since George Floyd’s death, amid nationwide protest the sports world was forced to revisit a legacy of insensitive mascots, songs and cheers.

“We always are trying to really exploit the beauty of the sport, the athleticism. We have a way to go with soccer,” she said. “The aerial camera added a lot to football. You have a point of view of what [the quarterback] is looking at, what are all his targets, what are his options.

“Similar for soccer. You really get the beauty of the sport, that it’s not about the individual. It’s a strategy of how he’s using his teammates and his vision of the field. It can be such a game of inches even though it’s over this incredibly vast field.”

ESPN isn’t planning on using fake crowd noise, which Rosenfeld likens to a laugh track, so players and coaches will be heard clearly —albeit after a seven-second delay to guard against coarse language. But that, like everything else in the MLS Is Back experiment, is subject to change.

“I don’t think that everyone is going to love everything,” she said. “But what a great time to see what sticks and maybe what isn’t so great.”