Effort to Americanize and monetize college sports in Japan faces obstacles

As one of the leaders behind a nascent movement to Americanize the athletic culture at Japanese universities, Kensuke Nakata draws inspiration from his early days as a college sports fan.

At first, he fell for the colors.

In his native Osaka, Japan, he never saw anyone wear clothing featuring the branding of their favorite university. But as an undergraduate at State University of New York College at Cortland, Nakata noticed students wearing their Red Dragons apparel, showing off their spirit for the school’s NCAA Division III athletic programs. Because of the close proximity, students also sported the orange of Syracuse University, which supported a nationally renowned men’s basketball team.

During his freshman year, in 2007, he began attending Cortland games and watching Syracuse on TV. He started to wear the gear too.

“It was a weird feeling,” Nakata says. “In Japan, it’s like people feel it’s embarrassing to wear a school’s name on your T-shirt.”

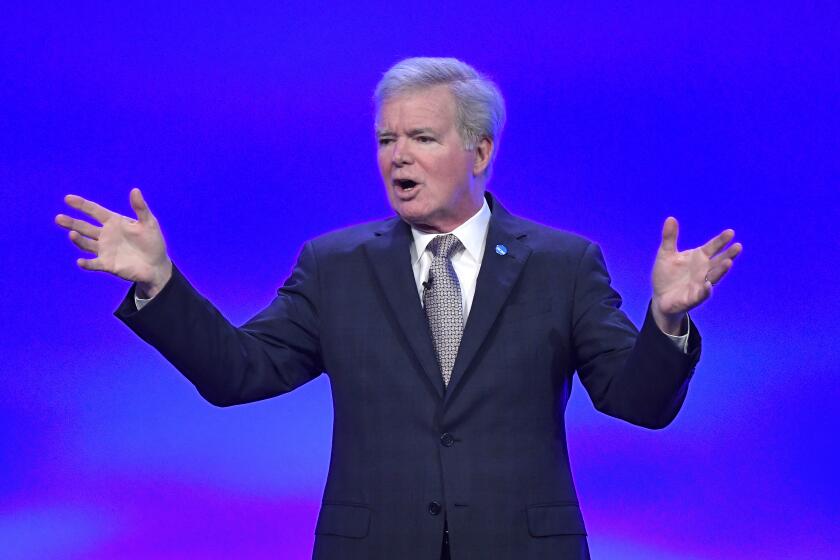

NCAA president Mark Emmert discusses demands for college athletes to be able to receive compensation for contributions that help bring in millions of dollars to schools.

As a sophomore, Nakata signed up for a bus trip to attend a Syracuse-Georgetown game at the massive Carrier Dome. He took in one of college basketball’s most heated rivalries with 30,000 others decked out in orange, blue and white.

“No words,” he says wistfully, more than a decade later.

Today, Nakata heads a research project driven by the Tokyo-based Dome Corporation, Japan’s official licensee of Under Armour. The company wants to flood a potential new market for its product by outfitting college sports teams in the same way Nike and Adidas made their push in the 1980s when NCAA games skyrocketed in popularity with increased television exposure.

While Nakata, 33, acknowledges that money is a factor in Dome’s interest in the American college sports model crossing the Pacific, his passion for the pageantry remains wondrous and innocent — even as he and a group of delegates to last week’s NCAA convention in Anaheim heard about the current crisis facing the century-old U.S. governance organization.

The NCAA decision to alter its player compensation rules in the aftermath of California passing its “Fair Pay to Play Act,” which allows college athletes to profit from their name, image and likeness starting in 2023, might feel weighty stateside, but the Japanese proponents of an NCAA-like model face more basic challenges.

Things such as: the inability to host games on college campuses; the control of all athletic events resting in the hands of the Japanese Assn. of Athletic Federations, which is responsible for training and developing the country’s Olympians and stages games at its neutral facilities; and a precedent for all college teams to function like club sports in the U.S., with zero university involvement.

The chair of the NCAA Division I council says the body is committed to drafting new proposals for regulating name, image and likeness of athletes by April.

In 2016, Nakata joined Shinzo Yamada, a senior associate athletic director at the University of Tsukuba (pronounced scuba) and a former XFL and NFL Europe player, to start the research project with Temple (Pa.) University’s sport management program. Temple, which is sponsored by Under Armour, was a natural choice for a partner.

They’ve attended the annual NCAA convention each year, bringing different representatives from across the Japanese sports, education and business landscapes, and in 2017 hosted NCAA President Mark Emmert for a visit.

“We didn’t just come up and say, ‘Let’s do this right away,’ ” Yamada says. “We said, ‘OK, why is this happening? What is the NCAA? What is an athletic department? What is a conference?’ Those kind of things.

“I’m sure we cannot copy everything. We decided to copy the good.”

What is the good, then, in the eyes of the Japanese? The answer helps explain why a country would take on this peculiar American tradition. The opportunity to make the equivalent of many U.S. millions by capitalizing on the built-in loyalties of college students and alums is enticing, sure, but there is a perceived intrinsic value too.

“When you look at the U.S., the [school] president, athletic director, the university people, faculty members, students, everybody is involved,” Yamada says. “The most important thing that needs to happen in Japan is that the school needs to be responsible.

“We would like to have the concept of a ‘student-athlete.’ It has to be student first. In Japan, it’s athlete first.”

StudentPlayer.com is a website that employs crowdfunding techniques to connect college athletes with sponsorship opportunities available at schools.

Given the critical climate surrounding the NCAA and its mission — at the convention, it was noted that only 7% of a group surveyed about college sports trust the NCAA to act in the best interest of “student-athletes” — the Japanese visitors’ unvarnished image of the association comes off as naive.

Many in Japan, particularly in the government and the athletic federation, don’t share their belief in the benefits of the American college sports model.

“People in Japan say, when I talk about trying to create this, ‘Oh, there’s too much money. Are you trying to make money out of amateur sports?’ ” Yamada says.

Every aspect of pursuing this change appears daunting. To begin with, they have to convince the country’s sport power brokers that the current system needs fixing.

Japanese college campuses aren’t overflowing with colors representing student pride. Ultimately, does that matter? There is probably a reason the model of schools funding sports to compete against one another exists only in America.

The life of an elite athlete in Japan flows through the federation. High schools also do not support athletic teams, so there is no feeder system creating a frenzied campus culture.

According to Yamada, 46, who came up through the federation playing football, many elite athletes attend small colleges that specialize in training for their sport but provide a less well-rounded education than Tsukuba can offer as one of Japan’s largest public universities.

Plenty of Olympians have attended Tsukuba, but it would be hard to know it because college sports matches are rarely televised. The federation controls the media rights, keeping the revenue it creates within this structure.

In 2018, the Japanese government established the Japan Assn. for University Athletics and Sports (UNIVAS) and billed it as the country’s version of the NCAA. Similar to when President Theodore Roosevelt encouraged the creation of the NCAA in 1906, UNIVAS was started to help protect athletes from violence and serious injury in college sports.

But, there is one big difference: UNIVAS is run by the government, not the schools.

While the organization now includes 200 universities, Tsukuba is not one of them.

“We just felt as a university this isn’t the right model,” Yamada says. “This isn’t the will of the university. Also, the federation is involved too much. You need more independence.”

Through its sponsorship from Under Armour, Tsukuba now has its own gear, featuring school colors of teal and purple. They might have uniforms and licensed apparel, but, with UNIVAS and the federation running things, there are still no plans for teams to play games on campus.

“It’s hard to create a rooting culture,” Nakata says.

The Japanese delegation to Anaheim included representatives from seven other universities, and Tsukuba and Under Armour’s hope is that a governing body other than UNIVAS could be formed among like-minded schools that want more say in their sporting futures.

Certainly, patience will be required. Nakata plans to continue working toward the dream he conjured at SUNY Cortland and pursued at Syracuse as a graduate student who interned in the school’s athletic department: to bring a special part of the American college experience home. He imagines a day when Tsukuba and other schools have their own mascot and fight song.

His vision always returns to the colors. In Japan, every so often he sees someone wearing the gear of an American university, and he is compelled to greet them.

“I see, you know, UCLA, and I feel like, ‘Oh, he’s from L.A.,’ ” Nakata says. “I feel like I want to say hi to them. One time I saw someone wearing a Syracuse shirt in Osaka, and I just thought, ‘He must be my friend.’ ”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.