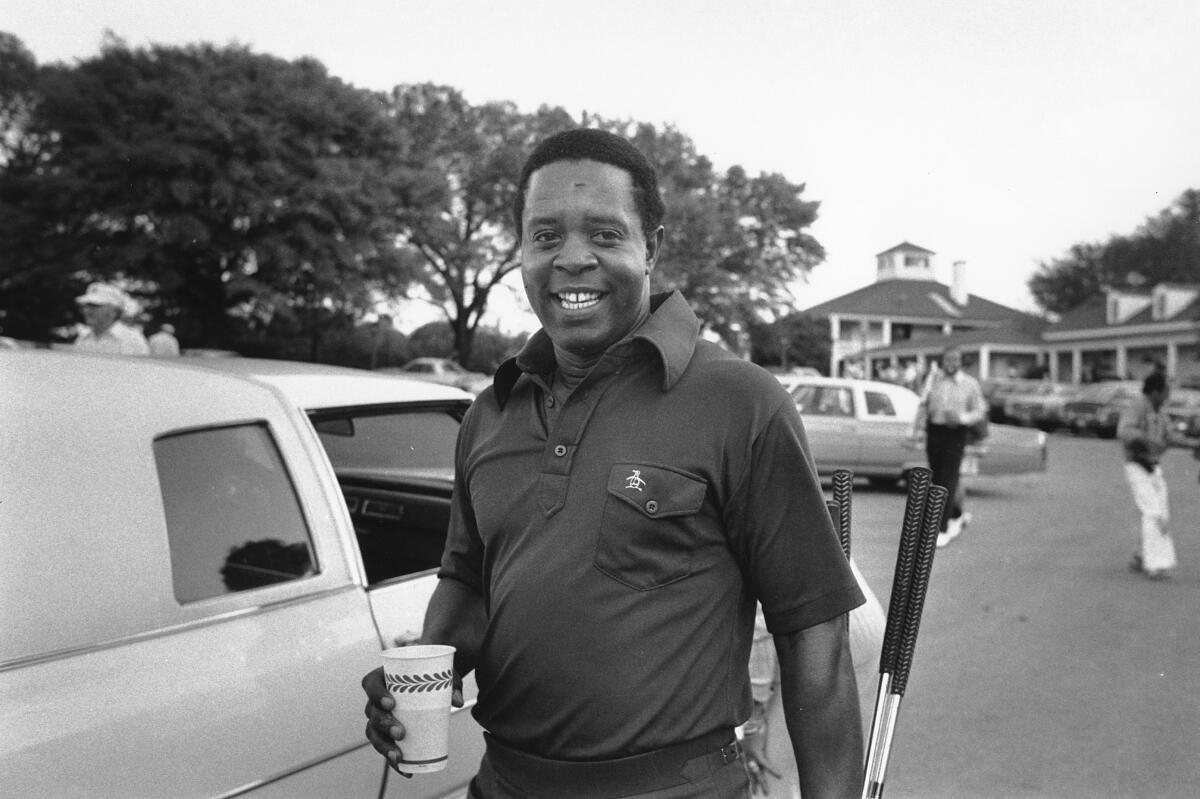

Lee Elder, first Black golfer to play Masters, dies at age 87

The pioneering Lee Elder, who in 1975 broke the color barrier as the first Black golfer to play in the Masters, died Sunday night at age 87. His death was announced by the PGA Tour and first reported by African American Golfer’s Digest.

Elder, who lived in a senior community in Escondido, was honored at Augusta National in April when he joined Jack Nicklaus and Gary Player on the tee box for the ceremonial first drives of the tournament. Although he couldn’t match the combined nine green jackets of those golf legends — his best finish at the Masters was a tie for 17th in 1979 — Elder garnered the loudest applause. He hoped to hit a shot of his own but instead acknowledged the gallery from his golf cart.

“For me and my family, I think it was one of the most emotional experiences that I have ever witnessed or been involved in,” Elder said following the ceremony, attended by dozens of Black club pros from around the country. “It is certainly something that I will cherish for the rest of my life.”

Elder made 448 starts on the PGA Tour with four victories, including the 1974 Monsanto Open in Pensacola, Fla., which earned him an invitation to the Masters. During that Florida tournament, he received death threats and was accompanied by armed security guards as he walked down the middle of the fairways.

“When I won at Pensacola, they had received calls that if I won the tournament I would never get out of there alive,” he told the Los Angeles Times in March. “So when I made the putt to win and I was going out to join my friends, Jim Vickers and Harry Toscano, they had beers in their hands ready for me. Jack Tuthill, who was then the tour supervisor, grabbed me and said, ‘Hey, you can’t go out there.’ I said, ‘Why can’t I?’ He said for me to get in the car so they could drive me back to the clubhouse. In the car, he told me about the threats.

Lee Elder, the first Black man to play at the Masters, has made a monumental contribution to golf and will appear alongside Jack Nicklaus and Gary Player at the 2021 event.

“The ceremony was given inside the clubhouse. We couldn’t do it outside. That was the decision of the people there. I was ready to get my trophy and my check and get out of there.”

The indignities that Elder and other Black golfers endured were a constant, including that Pensacola course once denying him entry to the clubhouse and making him use the parking lot to change into his golf shoes.

“I feel that several players should have been at the Masters before me,” Elder said. “You go back and look at Pete Brown, who won the Waco Turner Open in 1965. He was not invited. In 1967, Charlie Sifford won the Sammy Davis Jr. Greater Hartford Open. He was not invited.”

Sifford would win the L.A. Open in 1969. Brown won the Andy Williams San Diego Open in 1970. Still no invitations. So it was important to Elder to receive their blessing when he finally garnered a Masters invitation.

Fearing for his safety, he rented two houses in Augusta during his first Masters so people wouldn’t know exactly where he was staying. During the week leading up to the tournament, he and friends who had joined him on the trip from Washington were denied service at a local establishment because of their race.

Upon hearing that, Dr. Julius Scott, then the president of Paine College in Augusta, told Elder and his friends that chefs from the school would be preparing their meals for the rest of the week.

“He took us under his wing,” recalled Elder, who did not attend the historically Black college but felt a deep connection to it.

Last year, Augusta National endowed two Paine scholarships in Elder’s name and covered all costs of the university’s men’s and fledgling women’s golf programs.

“We hope that this is a time for celebration,” Augusta chairman Fred Ridley said, “and a time that will be a legacy, create a legacy, not only for Lee but for us that will last forever.”

Born July 14, 1934, in Dallas, Robert Lee Elder taught himself to play golf by sneaking onto all-white courses after hours as a youth. He did not play his first official round until he was 16. He caddied and hustled, and continued to improve when he was drafted into the Army in 1959 by playing frequent rounds with his commanding officer at Fort Lewis in Washington state.

Tommy Jackson always wanted to attend the Masters. He finally made it to Augusta National — the spring after he died.

Upon his military discharge in 1961, he joined the all-Black United Golf Assn. tour and launched his professional career.

In 1963, he and a quarter-million others participated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Elder and a friend walked three days to North Carolina, before hitching a ride the rest of the way to gather near the Lincoln Memorial to hear the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s historic “I Have a Dream” speech.

“It was fun starting out because you’re anxious, you’re excited about what’s going to happen,” Elder recalled. “How close am I going to get once I get there? How close are we going to be to him?

“Not very close. We were at the far back end. All the people who had walked from shorter distances certainly got the best vantage points. We just kind of stayed back and listened to it. The microphone was loud enough so we could hear it.

“I felt that I was helping the cause by being involved in it, trying to do what I could to help in whatever way that I could. I felt that on the March to show how much I really cared about what was happening.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.