Take a tour of Team Liquid’s sleek training center in Santa Monica and find out what a day in the life of a Team Liquid esports athlete looks like.

- Share via

Lunch is served in the team dining room, the chef preparing chicken piccata and fresh greens, but there isn’t much time to eat.

Players finish quickly and head for the opposite end of their training facility, past a glass-walled office where coaches pour over game data, past a lobby filled with gleaming trophies. They file into a darkened meeting room to watch film, then commence with practice.

That’s when things get heated, everyone keyed-up now, a coach muttering: “This is ridiculous. We have to play better.”

Life on Team Liquid does not quite fit the video-game cliché. These aren’t teenage boys huddled in their bedrooms, tapping away at keyboards, joking with friends online. This is a professional esports franchise and the mood is serious. When scrimmages finally conclude, many of the players return home to keep practicing on their own past midnight.

“You can go for 15 hours and, physically, you can keep up,” one of them says. “The question is, can you keep up mentally?”

Team Liquid competes in the North American league for a popular game called “League of Legends.” Ownership spent millions of dollars — no one will say exactly how much — to assemble an all-star roster and create a sleek training facility in Santa Monica in a space that used to house actress Reese Witherspoon’s production company.

If all that money got the team favored to win a national title and qualify for the upcoming world championships in San Francisco, it also put the players under a microscope. As coach Andre Guilhoto says: “It’s no longer about playing for fun.”

Esports weren’t like this when Danish star Soren Bjerg signed his first pro contract a decade ago. Thin and bespectacled, only 26 but nonetheless an elder statesman in a young man’s game, he has watched the transformation year by year.

“Now I think you just need to work a lot harder,” he says. “There’s definitely a serious environment. For better or worse.”

If the life of a big-time gamer seems excessive, consider the numbers.

Esports — video games as competitive sport — have developed an ecosystem not unlike that of baseball or soccer. There are high school teams, college championships and cutthroat competition in the pros.

Also money. Lots of it.

Pro leagues based on games such as “League of Legends,” “Overwatch 2” and “CounterStrike” create revenue by packing arenas worldwide and live-streaming to an estimated 400 million viewers annually. The industry, by various forecasts, will generate as much as $2 billion this year.

“Their whole life revolves around the game. And it revolves around them performing.”

— Jonas Andersen, Team Liquid assistant coach

For context, the PGA Tour says its projected 2022 revenue is $1.5 billion, while the NFL reportedly generated $11 billion in 2021.

Team Liquid is a major player, fielding squads in 18 different games and attracting investors such as Magic Johnson and Peter Guber, part-owner of the Dodgers and Golden State Warriors.

Financial backing helped build the Santa Monica facility with its 15,000-square feet of glass walls and glowing light, high-tech computer hardware, a 100-gigabite fiber optic network and video editing bays. Also, a couple of zero-gravity massage chairs. It paid for free agents who command far more than the league’s minimum salary of $75,000 a season.

Ownership went on a spending spree — picture the Dodgers of esports — raiding international rosters to sign Bjerg and Lucas Larsen from Denmark, Gabriel Rau from Belgium, Steven Liv from France and South Korean star Yong-in Jo. Like all gamers, each came with a nom de guerre: Bjergsen, Santorin, Bwipo, Hans sama and CoreJJ, respectively.

The ecosystem of competitive esports

This is the first of three stories examining the lives of esports athletes.

🎮 Part 2: California’s esports powerhouse isn’t USC or UCLA. Here’s a look at UC Irvine Esports

🎮 Part 3: Prep esports teams like Quartz Hill are preparing future pros

Winning was only part of the job description; players must churn out videos for the fanbase, promote merchandise and make commercials for corporate sponsors such as Honda and Verizon. The schedule is so busy that, during an eight-month season, everyone stays in apartments across the street.

“Their whole life revolves around the game,” says Jonas Andersen, a former pro who now serves as assistant coach. “And it revolves around them performing.”

Which made it all the tougher this season when the vaunted Team Liquid started to lose.

It doesn’t take long for young gamers to discover if they have what it takes.

In a digital universe, beginners can compete around the clock and watch livestreams of their favorite pros in practice, learning tips and asking questions. Imagine running beside LeBron James in a pickup game while he narrates each move. Millions of players enter the “League of Legends” ranking system, their results automatically recorded as they try to climb the list.

“If you’re not able to reach a very high level whilst at school,” Bwipo says, “you’re probably not going to make it.”

The 23-year-old with curly black hair is thoughtful and detail-oriented, given to long answers that verge on philosophical. He also serves as an example of how tough it can be to reach the professional level.

Showing promise at 17, Bwipo convinced his mother to let him drop out of school and play full-time. Next came several years of bouncing around low-level leagues in Turkey and Russia, working regular jobs back home during the offseason.

“The only results I saw were failure,” he says. “No trophy, no recognition, just nothing.”

Though he had “the fingers” — the dexterity to execute keystrokes in rapid-fire sequence — Bwipo’s mental approach needed improvement.

“League of Legends” resembles a game of “capture the flag,” with elements of chess added to the mix as two teams start at opposite ends of a jungle map. Each side has five players and each player controls a cartoonish character, known as a champion, tossing fireballs and casting spells, fighting to break through. It takes guile and teamwork to claim victory by reaching the opponent’s home base.

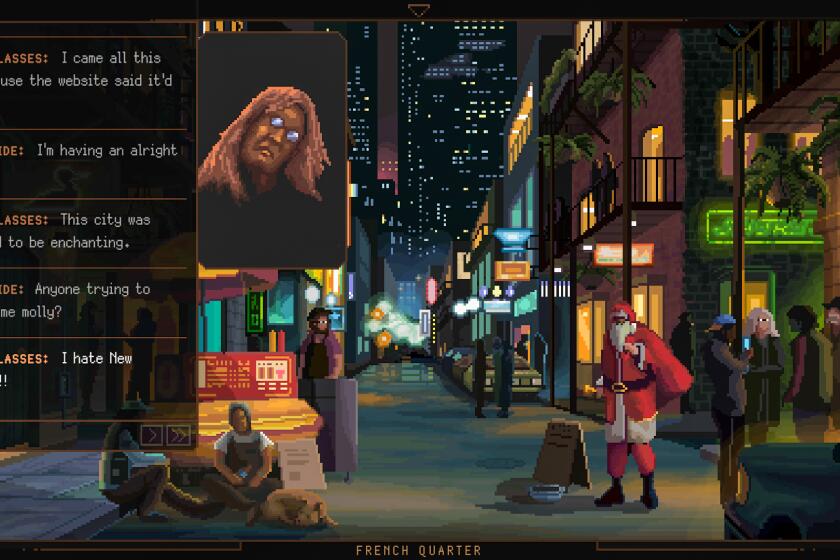

War exists for meme-making in ‘Norco.’ If you liked ‘Kentucky Route Zero,’ another game where we spend time with those on society’s outskirts, you may fall in love with ‘Norco.’

The action can seem bewildering, with champions flitting across the terrain, battling not only each other but also automated minions, monsters and powerful turrets. Each moment requires yet another snap decision as teams choose to remain at a safe distance or gather for an attack.

The best players, Bwipo says, have “a certain magic … they see patterns.”

For him, getting to that point required scraping together $120 for an online lesson with a respected coach. At a crossroads in his career, he planned to quit pro gaming if the session went badly, but the coach was impressed and word spread. Soon, a top team in Europe offered Bwipo a contract.

Earning a reputation for unpredictability, he committed occasional blunders but often parlayed innate creativity into spectacular kills. With numerous suitors to choose from — “League of Legends” has teams and leagues around the globe — he chose to sign with Team Liquid in North American last year.

“That’s the way you do it,” he says of forging a career. “You have to set expectations for yourself that are honest, that are brutal.”

Not all esports franchises spend so much on their teams. Many operate out of traditional “houses” — rented homes with living rooms full of computer hardware and everyone sharing bedrooms. But Team Liquid’s extravagance does not change a basic fact of pro gaming.

The workload can be as demanding as anything in the NFL or NBA.

Chronically sore necks, shoulders and wrists come with the job and sleep can be limited by late-night practices. The training center’s dining room is really just an excuse to impose nutrition on young men who might otherwise subsist on Red Bull and Flamin’ Hot Cheetos.

“It’s something we need to take care of,” says Guilhoto, a bear of a man who got his start coaching basketball in Portugal.

“Our mental practice is similar to chess. The way that we study the game is very, very intensive.”

— Andre Guilhoto, Team Liquid coach

Team Liquid chose Los Angeles as its U.S. headquarters because the city is an esports hotbed and home to an elaborate Westside arena where all 10 of the North American league franchises play their matches. The team’s training center is a mile away.

Players gather there on a recent day, crowding into the film room, which is painted black and has soft couches arranged before an expansive monitor on the wall. The regular season is concluding and the squad has yet to fully mesh.

In “League of Legends,” each of the five players assumes a specific role — top, mid, jungle, ADC or support — as part of an overall strategy. That means the stars on Team Liquid’s roster must suppress their egos, pushing aside any leading roles they may have played on previous squads. Before a practice scrimmage against rival Evil Geniuses, they get a chalk talk.

The soaring popularity of esports could put them up for serious consideration as an Olympic sport as the IOC looks to attract new and younger audiences.

“I have one point to make,” Andersen says. “I want to show you this.”

The big screen fills with whirling fantasy figures as the assistant coach discusses the draft that precedes every match. Teams go back and forth, choosing which champions they will inhabit. There are 161 options, each with slightly different powers that ebb and flow over the course of a season. Players have their favorites and coaches know which combinations work best for a given plan of attack, but teams must adjust on the fly, often reacting to their opponents’ pick the round before.

“Our mental practice is similar to chess,” Guilhoto says. “The way that we study the game is very, very intensive.”

Ready to make its selections, Team Liquid files into an adjacent “scrim” room where computer stations are arranged exactly like the “League of Legends” arena stage. A personal mouse and keyboard, a favorite snack and drink, await each player. Team manager Ben Zieper says: “If you touch their setup, that’s a bad idea.”

Evil Geniuses, playing from another location, log in nearly a half-hour late, which doesn’t sit well with the businesslike Team Liquid. The grumbling dies down only when drafting begins, followed by the start of play.

As coaches retire to the performance lab where they can watch an array of screens that show each player’s point of view, the scrim room gives itself over to a curious sort of music: Ticking keyboards and rapid chatter, players coordinating their movements. Language differences don’t matter because everyone speaks in the specific terminology of flashes and farming, scaling and Q damage.

Sitting shoulder to shoulder, fixing their eyes straight-ahead, the players rarely so much as glance at one another. The action grows louder and more frenetic over the course of 30 minutes, reaching a crescendo as the first game nears its end.

Oh my god.

It’s gonna be close.

We lost. We lost.

The scrimmage does not go well. Retreating to the film room, Team Liquid reviews its mistakes. Finding the “meta,” the best route to victory, means drafting wisely and making shrewd choices during the match, so Andersen focuses on a moment when his team should have taken advantage.

“But in this game, we didn’t,” he says. “We didn’t get anything.”

Though female gamers have become more prevalent, esports remain a male-dominated universe, with an emphasis on young males. The communication and cooperation required to win can be tricky for players who often share a similar background.

“If you’re locked in your room all the time, playing video games for years,” Bwipo says, “it turns out your social skills aren’t so good.”

A wrong move in the heat of battle can trigger angry words and matches can be lost to bickering. Like other pro franchises, Team Liquid employs a sports psychologist who encourages players to express themselves in calm, supportive words.

“Trying to reach that situation of blind trust,” Guilhoto says. “Knowing that you can do your role and the other teammate will do his role.”

Bjergsen recommends therapy for another reason.

Unlike other athletes who can walk away from booing crowds, gamers spend so much of their lives online in matches, practices and livestreams. The exposure to criticism is nearly constant and they can fall into a common trap, scrolling past compliments but lingering over nasty comments.

“I’ve seen a lot of people in the industry or teammates of mine really start losing confidence in themselves,” Bjergsen says. Even as an established star, his is careful to surround himself with “a solid kind of friend-group I can rely on.”

For Team Liquid, the scrutiny intensifies with a 12-6 regular-season record that one gaming website characterizes as “a failure and a wake-up call.” Then comes an early stumble in double-elimination playoffs, prompting an opponent to smirk: “They are supposed to be the super team.”

Climbing its way back through the lower bracket, Team Liquid reaches the third round but needs one more victory to secure a spot in the world championships.

The opponent? Evil Geniuses.

In the performance lab, the brightly antiseptic room at the heart of their training center, coaches do more than track matches.

This season, they have begun “brain mapping” players with computer exercises designed to analyze cognitive skills, reaction time and decision-making under pressure, a technology also being used by European soccer teams and air traffic controllers at an Amsterdam airport.

Team Liquid coaches hope it can determine the best positions — jungle, support, etc. — best-suited to each player. Charting results year by year, they want to see who slows with age and who can compensate by making wiser choices.

“Every single detail matters,” Andersen says.

The same goes for the business of esports. The team’s in-house production crew, working in an adjacent office with those editing bays, responds to the difficult season by redoubling its efforts. Players are encouraged to show more personality in sponsor commercials and let cameras follow them away from the game.

Esports giant Riot Games has grown into one of the region’s largest office tenants as the video game industry evolves into a major economic player.

“There won’t always be wins,” says Josie Brown, senior vice president of brand, content and marketing. “When fans come in behind closed doors, can hear the conversations … that means a lot when the standings aren’t great.”

Or when a super team falls short of expectations. As the North American playoffs grind to a close, there is no stirring comeback, no Hollywood ending.

The matchup against Evil Geniuses is decided by a game in which Bjergsen and his teammates start well enough but are caught off guard when opposing forces make a bold push. Champions stagger and turrets crumble. The home base falls.

Bwipo buries his face in his hands as Evil Geniuses celebrate onstage; CoreJJ shows little emotion, quietly packing up his headset and keyboard. Days later, Bjergsen is still making sense of it all.

“We had a lot of great players from a lot of different teams,” he says. “It felt like there was a stubbornness, a lack of flexibility, and we weren’t really able to see eye to eye around how to play the game.”

The franchise soon announces it will part ways with Hans sama and coach Guilhoto. There is speculation about additional departures soon.

With no more matches on the schedule, CoreJJ seems a bit lost. The 28-year-old South Korean with round glasses and a mop of dark hair decides to take a break from playing long hours each day and perhaps spend more time with his wife.

But in the realm of professional esports, where near-obsession is a given, he soon realizes that “maybe I am addicted.” His self-imposed hiatus lasts all of a week.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.