Underground London well beyond the Tube holds secrets and delights

It was one of those bright autumn mornings, ideal for wandering around leaf-speckled London parks. Instead, I was deep underground in a grubby old tunnel waiting for a train whose shiny green and red carriages looked considerably less roomy than, say, the Tube.

Mount Pleasant’s Royal Mail sorting office has been the center of London letter processing since 1889, but shuttling vast volumes of paper correspondence on congested city streets was a huge headache. The solution? A mini subterranean train line to keep the mail moving, and that is where I was.

From 1927 to 2003, Mail Rail zipped sacks of letters between sorting offices on 22 miles of private subway track. Few Londoners knew this secret underground line existed until a new Postal Museum opened last year, and the railway was reinvented as a ride for visitors.

Ticket in hand, I started in the brick-arched subterranean depot where the locomotives were once serviced. Several grease-streaked engines, each the size of a refrigerator on its side, were on display alongside time-capsule employee lockers bursting with grimy coveralls.

The original trains weren’t designed for passengers — the compact carriages were crammed with only bulging mail sacks — so the natty cars were built to fit their role as a ride.

After joining the excited queue, I inched toward the open doors of what resembled a miniature train.

I settled onto my tiny bench seat, enjoying the legroom budget airline passengers would recognize. As the doors snapped shut, I saw excited kids and giddy middle-aged train buffs glued to their windows. Soon, we were sliding toward the mouth of a dark tunnel just a little bigger than the train itself.

An audio narration from a retired Mail Railer described how the giant train set operated, with workers sorting letters at flood-lighted platforms. I imagined a close-knit gaggle of men discussing football, beer and tabloid headlines. There was even a dartboard on one platform, suggesting the workers knew how to keep themselves occupied between trains.

We rumbled through tunnels lined with studded iron ribs and streaked with electrical cables, past sandbags placed to halt runaway trains back in the day. Ghostly retired locomotives lurked on spooky unused sidings. In years past, the trains reached 30 mph, but today’s more sedate pace enabled passengers to view the route.

There were stops at two platforms, where short movies projected onto the curved walls told stories of wartime bombings and the olden-day process of handwriting letters and having them delivered several days later — a novel idea to some of the train’s younger passengers.

Twenty minutes later, we were back where we started. I hopped off, climbed the steel stairs and crossed the street to the main museum, an old red brick building that took several years to adapt.

The museum explores 500 colorful years of British mail history from red-painted stagecoaches and the 1840 introduction of the Uniform Penny Post system to the ever-evolving art of stamp design.

I spotted a Christmas card sent in 1843, said to be the first, and discovered that Britain’s famous red pillar mail boxes were originally green, necessitating a color change when countryside locals complained they couldn’t see them across their fields.

Yesteryear public information films were also screened, including 1936’s celebrated “Night Mail,” depicting the London-to-Glasgow letter-sorting train.

Thames Tunnel

The next day started with a tempest that had me searching for shelter. But rather than sticking to a standard indoor itinerary, I hunted down some of London’s other tunnel-related attractions, uncovering several subterranean gems that had stories of their own.

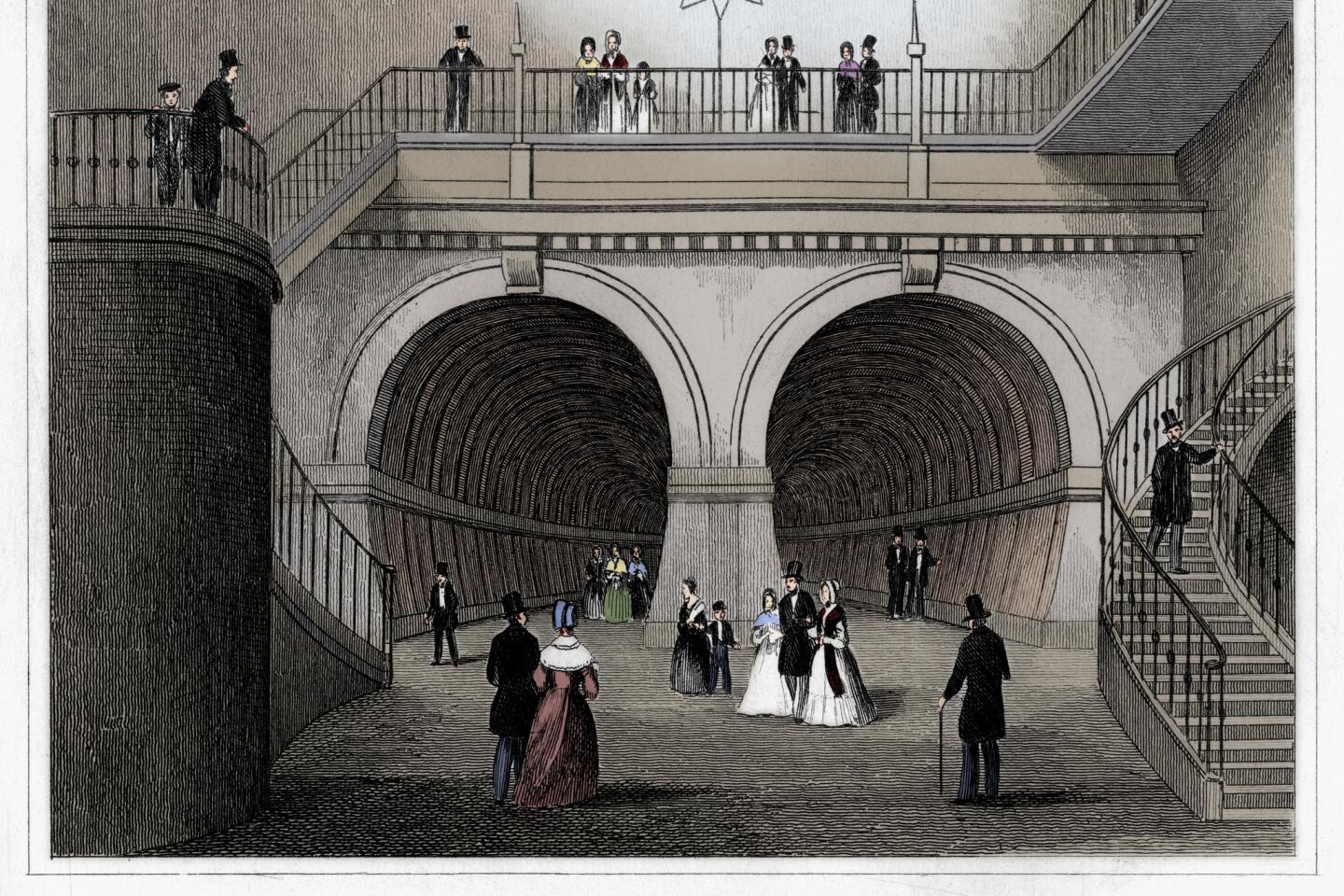

Victorian London’s best-known tunnel was intended for public use, unlike the Mail Rail. But locals had a long wait for access.

The problem? Building the long-dreamed-about Thames Tunnel, said to be the world’s first tunnel under a major waterway, was a challenge few had the engineering chops to deliver.

The tiny Brunel Museum tells the story of what’s now considered one of London’s great engineering feats, although it was a huge white elephant in its day.

The 1,300-foot tunnel, built by Marc Brunel and his son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, aimed to take horse-drawn carts under the Thames, easing heavily congested boat traffic.

But the tunnel was a commercial flop; flooding, collapses and bankruptcy fueled a 15-year overrun.

In the museum, I learned that after the tunnel’s opening in 1843, not a single cart ever trundled through.

For a short time, curious Londoners paid to promenade along the underwater route, enjoying stalls and fairground sideshows. But it was too late to make the project a success.

In 1869, the Thames Tunnel was sold to the fledgling London Underground system, and 192 years after it was started, it’s still used by trains each day, a testament to a project far ahead of its time.

A smarter underwater stroll

The 1902 Greenwich Foot Tunnel was a far more successful under-the-river route. It replaced a ferry that often failed to deliver area dock workers on time.

Its red brick-and-glass rotunda entrances, on opposite river banks, look like oversized bowler hats. It takes locals, tourists and cyclists (who are supposed to dismount but often don’t) between the north and south banks of the Thames.

The white-tiled 1,082-foot tunnel dips in the middle and feels colder at its center, 49 feet under the river.

For today’s visitors, the tunnel is a quirky add-on to their Greenwich visit, which might include the Cutty Sark clipper ship and the popular National Maritime Museum.

Picture-postcard views of Greenwich’s handsome Georgian skyline from the north side’s Island Gardens are also worth the short underwater walk.

On my visit, I was surprised to find the tunnel’s glossy-tiled walls almost completely devoid of graffiti — the polar opposite of the final tunnel I went looking for underneath London’s Waterloo Station.

Graffiti central

I had heard about Leake Street Tunnel many years ago but had failed to find it after making a half-hearted exploration of Waterloo’s sprawl.

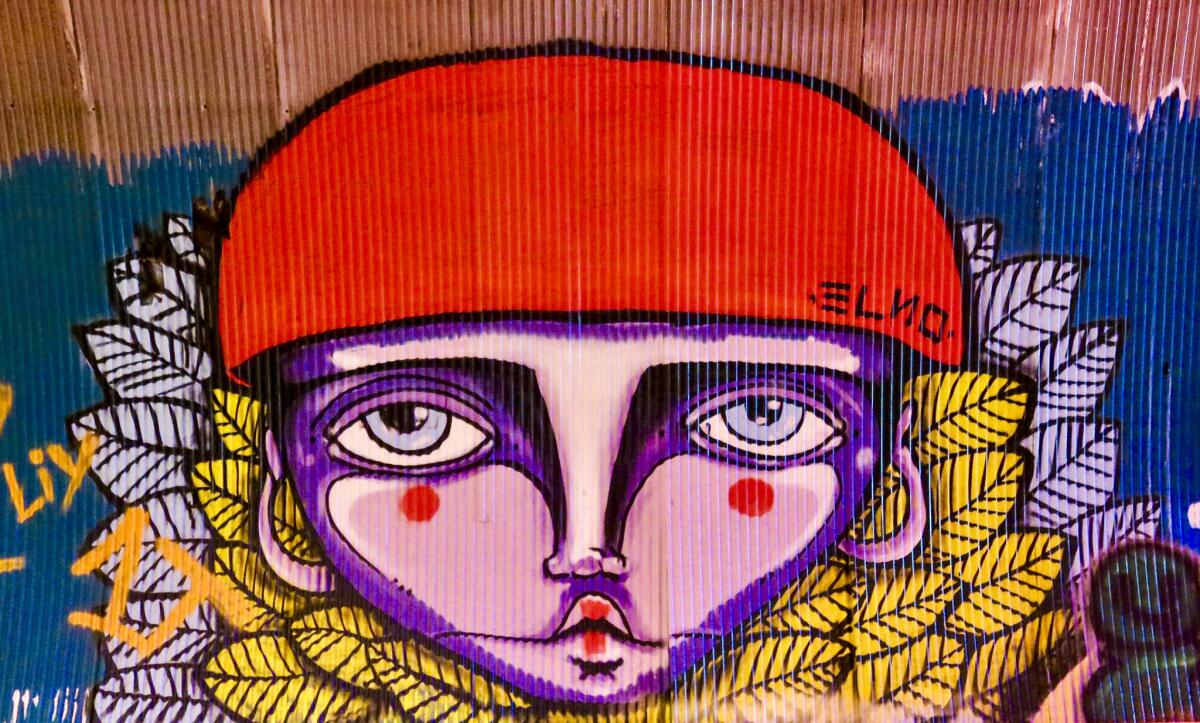

This time, though, I found it off York Road and joined the enthusiastic camera-wielders walking through a floor-to-ceiling gallery of ever-changing street art.

Every inch of Leake Street Tunnel is covered with graffiti. Although the quality varies (the authorities allow street artists to practice here, and anyone can leave their mark whatever their skill level), the standouts for me included oversized aliens and “Family Guy” characters making pithy political comments.

Colored lights give the tunnel a kaleidoscopic feel despite the dank, grubby ambience. But the number of camera-snappers shows how popular Leake Street is with in-the-know visitors.

I failed to find the Banksy works that launched it as a graffiti hot spot in 2008 — it was called Banksy Tunnel for several years — but few works here last more than a few days before being superseded by fresh creations.

Back outside, I tucked away my camera and headed to my hotel. It was close, so I could have easily walked, but a short trundle on the underground seemed the right way to end my day

If you go

Postal Museum and Mail Rail, 15-20 Phoenix Place, London. Open daily 10 a.m.-5 p.m. except Dec. 24-26. Adults $24. Nearest station: Farringdon.

Brunel Museum, Railway Avenue, London. Open daily 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Admission $8.50. Free for age 15 and younger. Nearest station: Rotherhithe.

Greenwich Foot Tunnel entrances are near the Cutty Sark (south) and in Island Gardens (north). Nearest stations: Cutty Sark for Maritime Greenwich (south) and Island Gardens (north). Open 24 hours daily. Free.

Leake Street Tunnel just off York Road, London. Nearest station: Waterloo.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.