Postcards From the West: Los Angeles’ Union Station

L.A.’s Union Station, the ‘last of the great train stations’ has been moving people and freight for more than seven decades.

Many movies have been shot at Los Angeles Union Station. But none can match the one you start filming in your head the moment you arrive from Alameda Street.

You fade in on the feet of a trendy young commuter, ear buds in place, rushing along the well-buffed tiled floor. The camera tilts up to reveal a homeless man dozing in one of the station's original leather-and-mahogany armchairs. You see a high, heavy chandelier, a grand arch, beams, stencil work.

It's a star in its own right, this building — a strange, graceful L.A. marriage of Spanish Colonial and Streamline Moderne styles — born in 1939, the last of the great American train stations. After a dismal slog through the late 20th century, Union Station is busier than ever, with about 10 times the traffic it had in its prosperous early years. Chances are it will soon be busier.

If you do your traveling by car and plane, you haven't seen the station in years, haven't harnessed your inner Hitchcock, haven't wondered where to hand off the mysterious suitcase, where the adulterers get down to business, where to stage the murder.

To the right, where the pay phones once were, you'll find the Traxx bar, ripe for eavesdropping.

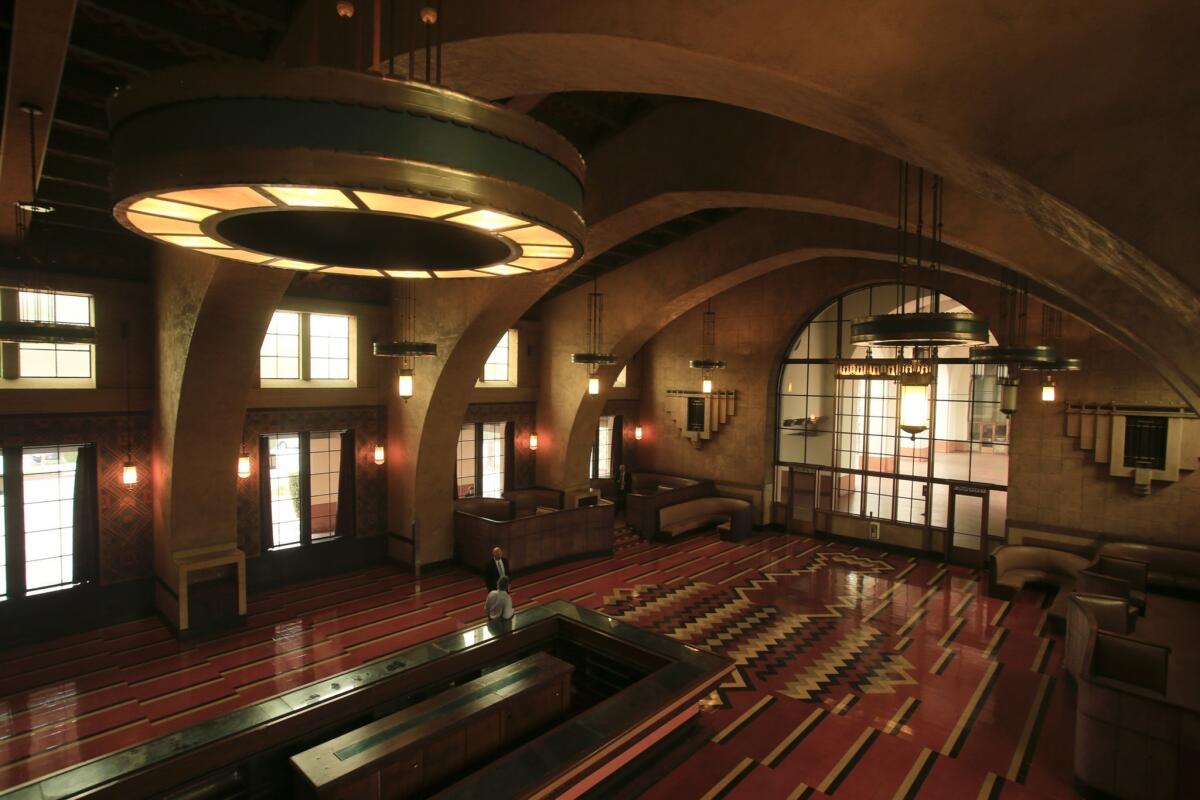

Just across the arcade, you have the station's original restaurant, a Harvey House designed by Southwestern architect Mary Colter. It's been closed (except for film shoots and special events) for decades.

To the left, you can lean on a movable counter left over from either a "Night Court" TV shoot or a "Blade Runner" movie shoot, depending on whom you ask. And from there you see the station's enormous and idle ticket concourse, suitable for occupation by the Phantom of the Coast Starlight.

Los Angeles Times photographer Mark Boster and I prowled the station for several days recently to finish our yearlong series on iconic locations, "Postcards From the West." (You can see the first half-dozen at latimes.com/postcards.) I was standing near the old ticket concourse, trying to recall plot points of "Union Station" (1950, starring William Holden) and "Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid" (1982, starring Steve Martin), when unscripted reality interrupted.

"My wife's had surgery!" an enraged Amtrak customer yelled at a security guard. "What is this, a museum or a … transportation center? You guys are pathetic! There's no help!"

The security guard stayed cool; the man stormed off; the human ebb and flow resumed.

Grandeur, grit, sepia light, flawed humanity — and that's before you even get to Wetzel's Pretzels. That food stand turns up, along with a sweet-smelling Subway, Starbucks, See's Candies, Ben & Jerry's Ice Cream and the convenience shop Famima, in the jumbled departure area just beyond the waiting room and before the long passage to the train platforms.

This is far more commercial life than the terminal saw from the 1960s to the '90s. Daily traffic is up to 60,000 to 75,000 commuters and travelers, depending on who's estimating. But as Metropolitan Transportation Authority officials acknowledge, the departure area could use better signage. (Amtrak and Metrolink do have motorized carts to carry travelers who have a disability, but station signs don't make that clear or explain how to summon one.)

If you walk down the long passage past the train platforms and under the tracks, you reach the station's east portal, built in the 1990s. Your reward for roaming waits above: a striking, 80-foot-wide multicultural mural of L.A. faces by Richard Wyatt, with an olive-skinned girl in a green blouse at center.

Born in 1939, Union Station is the last of the great American train stations. ( Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times ) More photos

To me, she's Our Lady of the Trains. Above her, the sun shines through a geometrically patterned skylight dome that would fit right in atop a mosque in Qatar. Without leaving the station, you've just traveled from one end of the 20th century to the other.

Beyond the station itself, things get tricky for a traveler, and many are put off by its proximity to the 101 Freeway, the county jail and the many panhandlers near Olvera Street. But the resurgence of downtown Los Angeles has brought new options beyond the usual Olvera Street shuffle. Walk several blocks from the station — or take a one-stop subway ride — and you can browse vintage vinyl and contemporary art in Chinatown, drink a $12 Asian Zombie under a string of lights in Little Tokyo or picnic on the grass of well-tended Grand Park, just across the street from City Hall.

Since the Metropolitan Transportation Authority bought Union Station in 2011, plans are afoot for more changes. Ken Pratt, Union Station's director of property management, said he has been courting prospective bar and restaurant tenants for the Harvey House. In as little as 18 months, Pratt said, "some inventive, eclectic, well-heeled restaurateur is going to come in here and do something marvelous."

Meanwhile, the MTA this year added a red-coated passenger assistance staff to answer questions. The MTA has also closed the station to non-passengers between 1 and 4 a.m. to give janitors more room and to discourage homeless people from treating the station as base camp. In some not-so-historic second-story space above Amtrak's ticket sales window, the rail line has quietly opened the private Metropolitan Lounge for its business-class and sleeping-compartment passengers.

In public spaces, there will be more movie nights and more live music, Pratt said, perhaps some artisan food services at the east portal in the next year, perhaps another restaurant in the now-idle space where Union Bagel once operated.

In the longer term, MTA executives are developing a master plan that would preserve the historical structure but add retail space, reroute the flow of bus traffic, allow for the arrival of a bullet-train connection to San Francisco by 2029 (if that costly, controversial project is completed) and improve transitions between the station and the neighborhood.

A space once occupied by the station's original restaurant, a Harvey House designed by Southwestern architect Mary Colter. ( Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times ) More photos

Executives say the MTA may even buy and knock down the privately owned Mozaic apartment buildings, an undistinguished complex next door that was built in 2006.

"We would be fine with that," said Adrian Scott Fine, Los Angeles Conservancy advocacy director. As for the MTA's larger ambitions? "The devil will be in the details."

But these changes could be years away, and plenty of ambitious Union Station plans have been floated and abandoned over the decades. Instead of holding your breath, savor the place as it is, grab one of those comfortable chairs, watch the passenger parade and polish your second act.

For instance, that "Night Court" / "Blade Runner" counter in the vestibule? Definitely big enough to hold a corpse.

Timeline: Keeping track of Union Station's history

May 1939: Los Angeles Union Passenger Terminal opens, linking the Santa Fe, Southern Pacific andUnion Pacific railroad systems, which used to operate separate stations. To make room for the new station, much of the city's original Chinatown was leveled. The station's design, conceived by the father-son architect team of John and Donald Parkinson, mixes Streamline Moderne and Spanish Colonial styles, along with Moorish accents here and there. The station's first timetable lists 33 arrivals and 33 departures daily.

1940s: Civilian traffic reaches an estimated 6,000 people a day. During World War II, traffic is far greater as troops are mobilized.

1950s: As automobile and air travel increases, the station becomes known as "the last of the great train stations" in the U.S.

1966: After decades of relying on trains to carry mail, the U.S. Postal Service shifts to using planes and buses. Passenger traffic dwindles too.

1967: The station's slowest year ever, with just 15 trains in and 15 out a day. The station's Harvey House restaurant closes.

1971: Congress creates Amtrak to take over passenger service from rail companies that are more interested in making money on freight. At Union Station, owned by the rail companies, passenger traffic remains thin.

A present-day photograph of Union Station contrasted with an old postcard image. (Photograph: Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times; postcard: Gardner-Thompson Co.)

1992: Catellus, a development company formed from real estate holdings of the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific railroads, begins a major restoration of the station. Also, Metrolink begins regional commuter rail service with Union Station as its hub, carrying 5,000 passengers on its first day.

1993: The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority opens the first 4.4 miles of the Metro Red Line, which will eventually connect Union Station to downtown Los Angeles, Hollywood and North Hollywood.

1995-1998: Gateway Transit Center, soon to be renamed Patsaouras Transit Plaza, opens at Union Station's east portal as a hub for bus service. Catellus sells station-adjacent property to several buyers including the MTA, which builds a 26-story headquarters, and the Metropolitan Water District, which builds a 12-story headquarters. Inside the station, owner-chef Tara Thomas' Traxx Restaurant opens; the station's old telephone room becomes its bar.

2003: MTA opens a Metro Gold Line light-rail stop, connecting the station with Pasadena.

2005: Catellus merges with industrial developer Prologis.

2011: The MTA buys Union Station and its 38-acre property for $75 million, making the landmark property public for the first time.

2013: Weekday traffic is about 10 times what it was in the 1940s — 60,000 people by some estimates, 75,000 by others. About 60 movies, TV shows and ads a year are shot on-site.

Sources: https://www.metro.net/about/union-station/history; https://www.metro.net/projects/la-union-station; https://www.prologis.com; "The Last of the Great Train Stations," by Bill Bradley, Pentrex Media Group, 2000; Jenna Hornstock, MTA deputy executive officer for countywide planning; Kenneth E. Pratt, director of Union Station property management.

Train station tourists can also do Civic duty

L.A.'s Civic Center is a short distance from the terminal with many attractive features.

It's a 15-minute walk — or a one-stop ride on the Red Line — from Union Station to L.A.'s Civic Center, where you'll find almost as many 21st century additions as Union Station has 20th century echoes.

Start with Grand Park (200 N. Grand Ave., https://www.grandparkla.org), a redesigned 12-acre public space that officials unveiled in 2012. Near the east (downhill) end, which faces City Hall, you'll find startling pink chairs and tables. Near the west (uphill) end, across from the Music Center, is a new Starbucks-adjacent fountain, where kids can wade. In between: picnic-friendly lawns, drought-tolerant landscaping and a couple of Little Library boxes where visitors can take and leave books. Open 5:30 a.m.-10 p.m., with a farmers market on Tuesdays, 10 a.m.-2 p.m.

The 12-acre Grand Park was unveiled in 2012. ( Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times ) More photos

Next, prowl around the Music Center of Los Angeles (135 N. Grand Ave., https://www.musiccenter.org), home to the Center Theatre Group, L.A. Opera and L.A. Master Chorale, on your way next door to shiny, curvy, 10-year-old Walt Disney Concert Hall (111 S. Grand Ave.; [323] 850-2000, https://www.laphil.org), home to the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Hourlong guided tours and self-guided audio tours of Disney Hall (exterior and lobby only) are offered most days between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. ([213] 972-4399, https://www.musiccenter.org/visit/Exploring-the-Center/Tours).

Other cultural options nearby include the Colburn School (200 S. Grand Ave.; [213] 621-2200, https://www.colburnschool.edu), a performing arts conservatory with three concert venues and a pleasant cafe, and the adjacent Museum of Contemporary Art (250 S. Grand Ave.; [213] 626-6222, https://www.moca.org).

Walt Disney Concert Hall, located across from Grand Park, is home to the Los Angeles Philharmonic. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) More photos

But wait. There's more coming. Late next year, the Broad Museum (221 S. Grand Ave.; https://www.thebroad.org), a contemporary art space bankrolled by mega-philanthropists Eli and Edythe Broad, is expected to open across the street from MOCA. Will MOCA and the Broad be frenemies? Almost certainly.

If you still have energy after all that walking, it's about two blocks from MOCA to the soaring beige Minimalism of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels (555 W. Temple St.; [213] 680-5200, https://www.olacathedral.org).

Even if you don't go in, be sure to notice the 8-foot-tall statue of Our Lady of the Angels above the entrance. Sculptor Robert Graham made her a confident young woman with long hair and features that might be Latina, Asian, African, Caucasian or Native American.

'Mystery, history and grandeur' at Los Angeles' Union Station

Union Station: L.A. Conservancy tour volunteer Holly Kane talks about some of her favorite spots at the downtown transit site.

L.A. Conservancy tour volunteer Holly Kane has guided groups through Union Station since 2009. ( Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times ) More photos

Whenever she gets a chance, Holly Kane herds strangers into Union Station and rolls back the years.

"The history of railroads is the history of Los Angeles," she tells them.

Kane is a relative newcomer to this history, having moved to Los Angeles from Ohio in 1987. But she wrote her master's thesis (for USC's School of Architecture) on historic preservation at the station and has volunteered to lead tours there for the L.A. Conservancy since 2009.

After explaining how the rail barons of the day agreed to share a single station (hence the name Union Station), she might step over to the old ticket concourse, where civilians are forbidden but Conservancy tour groups are permitted to tread.

"Mystery, history and grandeur," she says. "It's a vast space. You could fit a five-story building inside.… Imagine the bustling crowds that would come in to buy tickets to cities like Chicago, St. Louis or New York."

In the early 1940s, the men's room had a four-seat barbershop; the women's, a lounge. "So you can imagine women with hats and gloves and dapper gentlemen freshly shaved and ready for first-class train travel."

Civilians aren't allowed to walk through the old ticket concourse, but you can gain access by participating in an L.A. Conservancy tour. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) More photos

No, Union Station isn't like that anymore. But Kane keeps coming back. Three more of her favorite spots:

• The vestibule, just inside the main doors. If you stand near the information booth and look up, Kane says, "you can see the ceilings in four different rooms. This is cool. Each one is different. They look like wood, but they're concrete. And those huge circular chandeliers are 10 feet across and weigh 3,000 pounds. The weight of a small car. If I tell them that while we're standing under one, they usually jump. Especially the kids."

• The south patio, a.k.a. the arrivals patio. This is where fresh arrivals would step out of the station "and walk into a beautiful Southern California vista," says Kane. "Pepper trees. Birds of paradise. Palm trees." Thanks to restoration, she adds, the area looks much as it did in those early years.

• The departures area. This is not because it's beautiful or easily understood, but because it's a transitional moment. "As soon as you step from the high ceilings of the waiting room into the departures area, all of the architecture becomes more utilitarian," Kane says, with low ceilings, artificial light and a sudden "sense of activity and motion." When Kane started giving tours four years ago, her Conservancy-approved script said that 30,000 people per day were passing through the station. Now it says 75,000, and Union Station's master plan forecasts a jump to 100,000 as the Metro system expands in coming years.

christopher.reynolds@latimes.com

More Postcards From the West

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.