How Russia’s biggest rock star gets away with speaking truth to power (a.k.a. Putin)

MOSCOW — In Russian culture, there is a persona referred to as yurodiviy, or holy fool, whose madness gives him impunity to speak the truth to the czar.

Sergei Shnurov is modern Russia’s holy fool.

Shnurov built a punk rock career singing about getting drunk, having sex and getting by in the chaos of post-Soviet Russia. His lyrics about the paradoxes of modern Russia, often critical of the Kremlin’s notion of traditional values, are littered with words so vulgar that most of his songs never make it to the radio.

Yet, despite Shnurov’s disdain for contemporary Russian political culture, he and his band, Leningrad, don’t worry about authorities canceling their shows — a common fate for popular entertainers who have spoken out against the Kremlin or promoted the wrong kind of values.

Shnur, as he is widely known, is beloved by a wide swath of Russians. Police officers love him as much as tattooed hipsters and their middle-aged parents. Oligarchs hire him to sing at their birthday parties, and he has hosted shows on state-funded television. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s first wife once famously danced to Leningrad’s music with a group of students in a viral video.

This bizarre combination of Russian rude boy and favorite of the ruling elite makes Shnurov incredibly popular, controversial — and the most successful rock star in modern Russia.

“Shnurov is a very clever guy, a very well-educated guy. But he plays a fool,” said Yuri Saprykin, a journalist, critic and essayist on Russian culture.

“He’s popular because of his humor and his cynicism about everything here,” Saprykin said. “He is not just a rude boy who is swearing. It’s poetry. It’s funny, it’s edgy.”

In Russian Orthodoxy, the best known of holy fools is Nicholas Salos of Pskov, a 16th century self-styled prophet who famously reprimanded Ivan the Terrible for his brutal campaigns and persuaded him not to sack the western Russian city of Pskov.

Shnurov is a decidedly modern prophet. He can get on stage one night to entertain the Kremlin elite with R-rated lyrics about drinking too much vodka and having sex, then stand before the Russian Duma, the country’s parliament, to criticize the government for trying to regulate creativity through the Ministry of Culture.

“No normal country has a culture ministry!” Shnurov told the legislators in his raspy voice, hoarse after years of smoking. Shnurov had been invited to be a member of the Duma’s Committee on Culture. The singer took the opportunity to suggest that the culture ministry itself be abolished.

“It’s just theoretically impossible to regulate producers of culture,” Shnurov said in the February appearance, looking straight into state television cameras as he addressed the parliamentary committee. “This is not going to work, because ... any artist, any blogger, or anyone who has Twitter can be the producer of ideas and the producer of culture, no matter how awful it looks to you.”

The comments seemed to drive directly at the heart of Putin’s “managed democracy,” in which the former KGB officer has created a vertical power structure with the Kremlin on top.

Many of Russia’s most popular entertainers have been punished for speaking out against the Kremlin. Putin’s system has pushed the idea of traditional, Christian values as part of Russia’s core identity. Patriotic themes are encouraged, while criticism of the Soviet past is dismissed. Russian musicians who openly criticized Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 had their concerts canceled or received threats from Putin supporters.

Yet, in an interview before a Moscow concert this summer, Shnurov dismissed accusations that Russia is a censored state controlled by Putin.

Shnurov is old enough to remember censorship as it was practiced in the Soviet Union before its collapse in 1991. “Today it is very funny to talk about censorship when we have the internet,” he said, sitting in a backstage lounge the night before the sold-out show. With the band calling it quits this year after playing together for more than 20 years, it was one of the last concerts Leningrad would play in Moscow.

Despite Shnurov’s critical stance on many of Russia’s political developments over the years, he said he did not believe Putin is an autocrat whose strong-arm rule is ruining Russia. If Russia is turning toward the past, Russians themselves must take some of the blame, he said.

“Luckily, not everything depends on Putin. I don’t depend on Putin,” Shnurov said. “These concerts don’t depend on Putin. There is no totalitarianism.”

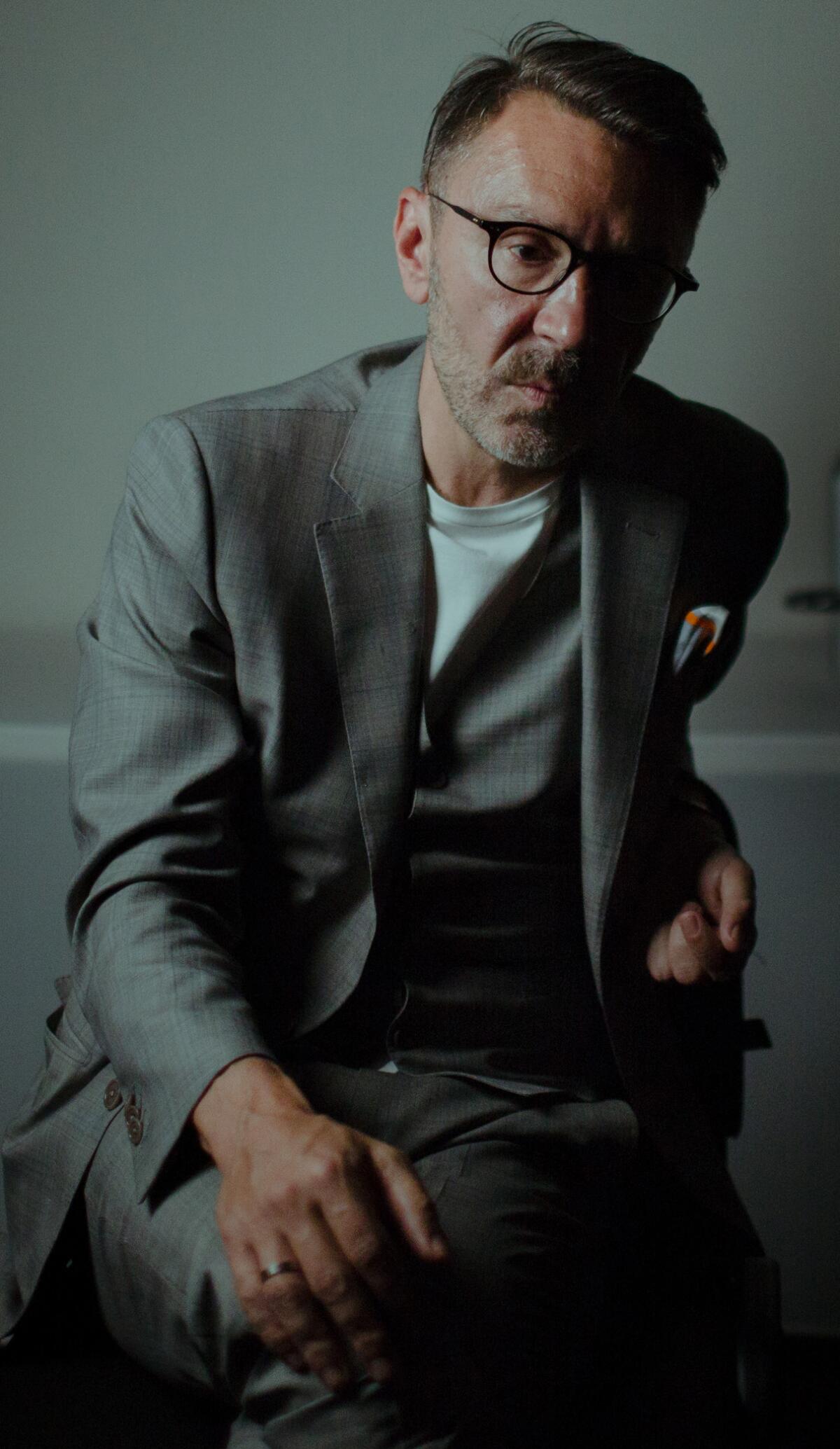

At 47, Shnurov still has the energy of a young performer. He still sings about heavy drinking and partying, but in recent years, he has embraced running and a bit of healthy living. His stringy long locks of the early 2000s have been replaced by an Ivy League cut. He wears a three-piece gray suit over a white T-shirt.

He’s smart and articulate, and his eyes light up when it’s clear he’s made a connection.

Like Putin, Shnurov is from St. Petersburg, Russia’s second largest city and the former home to the czars. The men’s careers developed almost in parallel.

Shnurov’s band, Leningrad (the Soviet name for St. Petersburg), started out “as just a joke” in 1997 between a few friends who liked to make music. Meanwhile, Putin, a former KGB officer, was rising through the ranks of St. Petersburg city government and then Moscow’s political elite. In 2000, Putin was elected president as Boris Yeltsin’s hand-picked successor.

At the time, Leningrad — the band — was dominating Moscow and St. Petersburg’s underground music scene, with Shnurov as guitarist and lead singer. The band’s lyrics spoke to the average Russian not interested in geopolitical scandals but in complaining about the irritations of daily life.

Shnurov has always insisted he wants nothing to do with politics.

“I’ve read somewhere that ‘rock and roll’ is a euphemism for [sex],” he said. “It doesn’t have any relation to honesty, protest, any kind of social diagnosis. It relates only to lust, idiocy ... and alcohol in my case.”

By the early 2000s, Leningrad was selling out large concert arenas. In 2002, former Moscow Mayor Yuri Luzhkov banned the group from playing in the capital’s biggest venues. Officially, the ban was because of vulgar lyrics, but many believed it was because of Leningrad’s subtle criticism of the political elite.

Leningrad and Shnurov made huge amounts of money as Russia’s most popular band. Forbes magazine estimated in 2018 [link in Russian] that Shnurov was worth about $14 million, making him Russia’s second most successful entertainer after Alexander Ovechkin, a Russian-born hockey player on the Washington Capitals.

“The thing that is interesting about Shnur is that he’s gone from a small punk scene to huge concert halls,” said Clem Cecil, the director of Pushkin House in London, a nonprofit, non-governmental Russian culture center. “He’s charismatic and gives people a really good time. He’s a glamorous rock star, but there’s still that punk element about him.”

And while Shnurov’s style and music have become a social commentary, he is more than anything a showman and a cunning businessman, Cecil said.

Shnurov describes Leningrad’s original sound as a mixture of vampire rock mixed with Soviet prison music and brass instruments to give it punch.

In recent years, Shnurov has pivoted toward music videos with satirical criticism of Russia’s haphazard post-Soviet development.

The catchy “In Peter, Drink!” depicts a bad day for a St. Petersburg office worker that turns into a drinking marathon. It’s both a love song to Shnurov’s hometown and a mockery of Russian stereotypes and their reality, all wrapped together in an addictive chorus.

In “Exhibit,” which has been viewed more than 148 million times, a young Russian woman tries desperately to impress a suitor by painting the bottom of a borrowed pair of high-heeled shoes with bright red nail polish to look like a pair designed by Christian Louboutin.

Admiring herself in the mirror, the woman turns to go answer the door when she realizes that the nail polish on the shoes has stuck to her apartment’s floor, and she falls flat on her face.

It has become one of the most viewed Russian videos of all time, and it exemplifies the Russia Shnurov says he loves but is pessimistic about.

“I think that Russia has turned its head a little bit back. There is a lot of attention paid on what had happened and not on what will happen or what will be,” he said. “This conservative situation doesn’t mean any development, any future. If we always remember our great past, then where is our great future?

Shnurov this year announced that Leningrad was going on its final tour. In addition to shows across Russia and Europe, the band will give four performances in the U.S. in November, in New York, San Francisco, Seattle and Miami.

He has not decided what his next artistic endeavor will be, nor is he in a rush to find it.

“It’s not necessary to constantly produce something. Look at the ‘Catcher in the Rye’: That dude wrote one novel and that’s it, and then he just ...”

True to form, he ended the sentence with words that can’t be printed here, but make his fans love him even more.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.