Meet the man whom Hong Kong’s embattled extradition law is all about

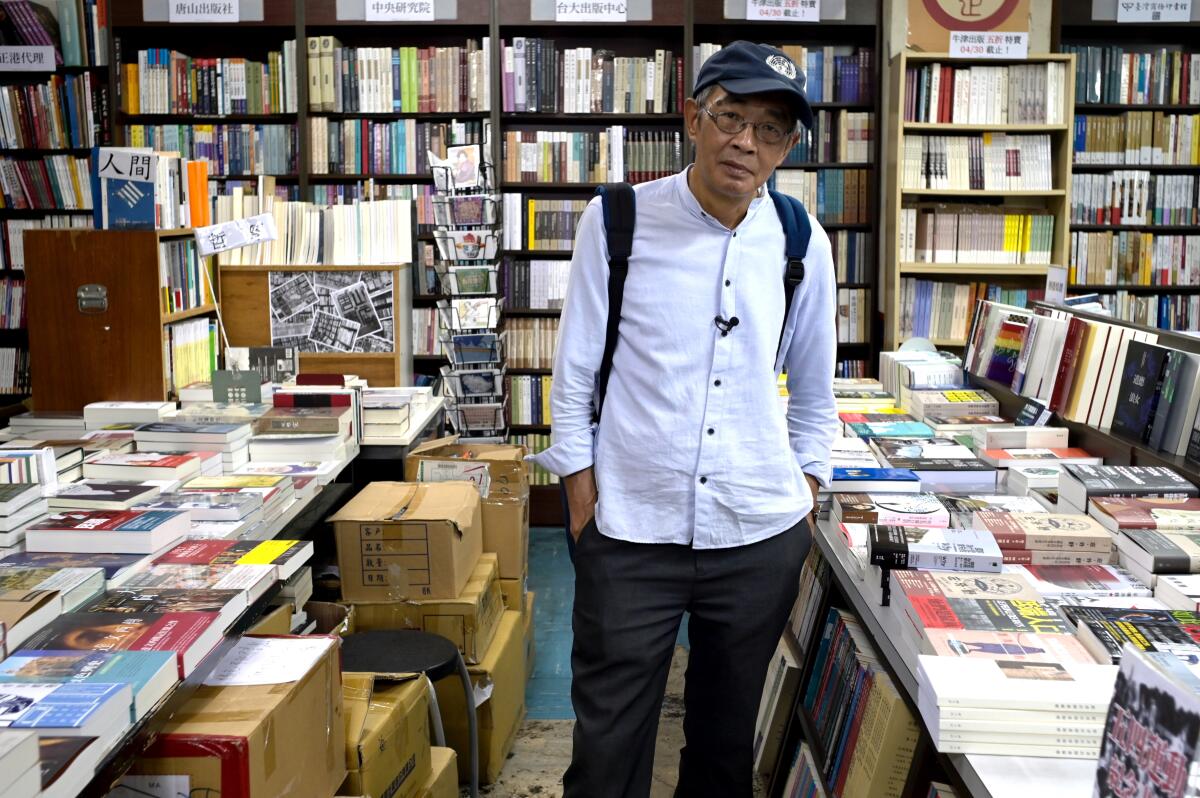

TAIPEI, Taiwan — Lam Wing-kee shields himself in a sunhat like a lot of Taipei dwellers as he walks across sun-splashed plazas in the 95-degree heat. Further blending in, the 63-year-old drinks coffee in the Taiwanese capital’s cheap breakfast bars, and later in the day he might check out the city’s ever-popular bookstores.

Lam is no ordinary Taipei guy. He’s a core reason behind the summer of protests in Hong Kong — a string of events that have put the city on edge and turned eyes toward Beijing as it marshals paramilitary troops just outside the territory.

The Hong Kong citizen is wanted by mainland China after snubbing an investigation into his sales of sensitive books about Chinese leaders. Lam is one of five Hong Kong booksellers detained by Chinese authorities in 2015, stirring concern that Beijing was curtailing freedom of expression in the former British colony that it took over in 1997.

Chinese investigators had released Lam into Hong Kong, after eight months of detention in the mainland, to allow him to retrieve his computer and mobile phone, and then go back to China. But he never went back. And Hong Kong couldn’t force him to go, because it lacks an extradition law.

Then in February, Hong Kong leaders proposed just such a law, eventually sparking the protests that have raged since June with increasing levels of violence. Under the proposed law, Beijing would technically be able to extradite Hong Kong citizens, who are used to freedom of speech, and prosecute them for any anti-Communist Party views.

Lam escaped to Taiwan this past April. “I’m a bit worried now, because they won’t necessarily let me go back in,” Lam said in an interview last week.

Hong Kong’s chief executive said Wednesday she would drop the proposed extradition law, making it safer for Lam to return. But he still faces the threat of arrest, a tool that Hong Kong authorities are already using to stop protests. About 1,100 protest-linked arrests have been made so far, demonstration organizer Joshua Wong estimated Tuesday while himself traveling in Taipei.

“It helps to placate people’s outrage,” Lam said when he heard about the extradition law being dropped. “But what Hong Kong people worry about most now is abuse of police power and no guarantee of personal safety.”

Lam said his case began when undercover Chinese agents visited his bookshop, Causeway Bay Books. The career Hong Kong bookseller founded the store, located in a dense commercial district popular with tourists, in 1994 and sold it to the local publisher Mighty Current Media Co. in 2014. He stayed on as store manager.

“They had snuck into my bookstore to look” he speculated. “A bookstore after all is open to the public.”

Lam said that in the past he would take books into mainland China and mail them from there to customers. After China asked him to stop that in 2012, he said he mailed some from Hong Kong. His store also got customers visiting Hong Kong from mainland China.

A title that mentioned the private lives of Chinese leaders — forbidden on the mainland itself — earned about $3.83 million across all sales channels, Lam said.

In 2015, Lam was pulled aside while crossing from Hong Kong into the mainland Chinese city of Shenzhen and taken to a detention center in Ningbo, near Shanghai, where he said the windows were so high he couldn’t see out.

He lived alone there for five months before being moved to a hotel in Guangdong province for another three. Lam said he was interrogated “viciously” several times a week.

Lam said Chinese police ultimately let him back into Hong Kong to get his computer, figuring it would contain files useful for their investigation. He checked into a Hong Kong hotel, as agreed with Chinese authorities, but shortly after that, in June 2016, Lam told a news conference he would not return to the mainland.

As the protests unfolded in June 2019, Lam said he was surprised only by the forceful police response. “I didn’t expect the Hong Kong government would handle things in this way,” he said, accusing the police of being agents for mainland China.

Lam’s move to Taipei in April spotlights Taiwan’s uneasy role in the protests.

China claims sovereignty over self-ruled Taiwan and has threatened to eventually take control of it by force, if necessary. Officials in Beijing resent Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen for refusing to accept Taiwanese unity with China — and for speaking out in support of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy demonstrators.

“Mainland China wants unification, that’s clear,” Lam said. “They’ll try to get Taiwan after Hong Kong.”

During his visit this week, Wong urged Taiwanese to hold protests of their own this month as a show of support for activists in Hong Kong.

And, noting that Taiwan also has no immigration laws that would let Lam seek political asylum. Wong said he came to push for one.

“Proactive help from Taiwan for Hong Kong, I believe, would earn the support of common Hong Kong people,” Wong told a Taipei news conference Tuesday after urging legislators to pass an asylum bill that’s stuck in parliament

Lam said he doesn’t expect the asylum bill to pass, because of China itself. “I think a lot of Taiwanese would oppose it,” he said. “They worry mainland Chinese would use Hong Kong as a base to apply for asylum. Some would be fakes.”

He said he plans to travel to a book fair in Germany in October and return to Taiwan on a new tourist visa. Without a path to asylum, he said, he could live like that indefinitely if it remained unsafe for him to reenter Hong Kong. His wife, two grown sons and an older sister still live in his homeland.

Lam said he visits Taipei’s bookstores partly to grasp the market in Taiwan, which like Hong Kong is ethnic Chinese and Chinese language-literate, but with little interest in the private lives of communist leaders. His next move — a crowdfunding campaign to raise money for his own Taiwan bookstore — raised more than $110,000 in a single day on Friday.

Jennings is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.