Tent courts open as latest hurdle for migrants seeking asylum in the U.S.

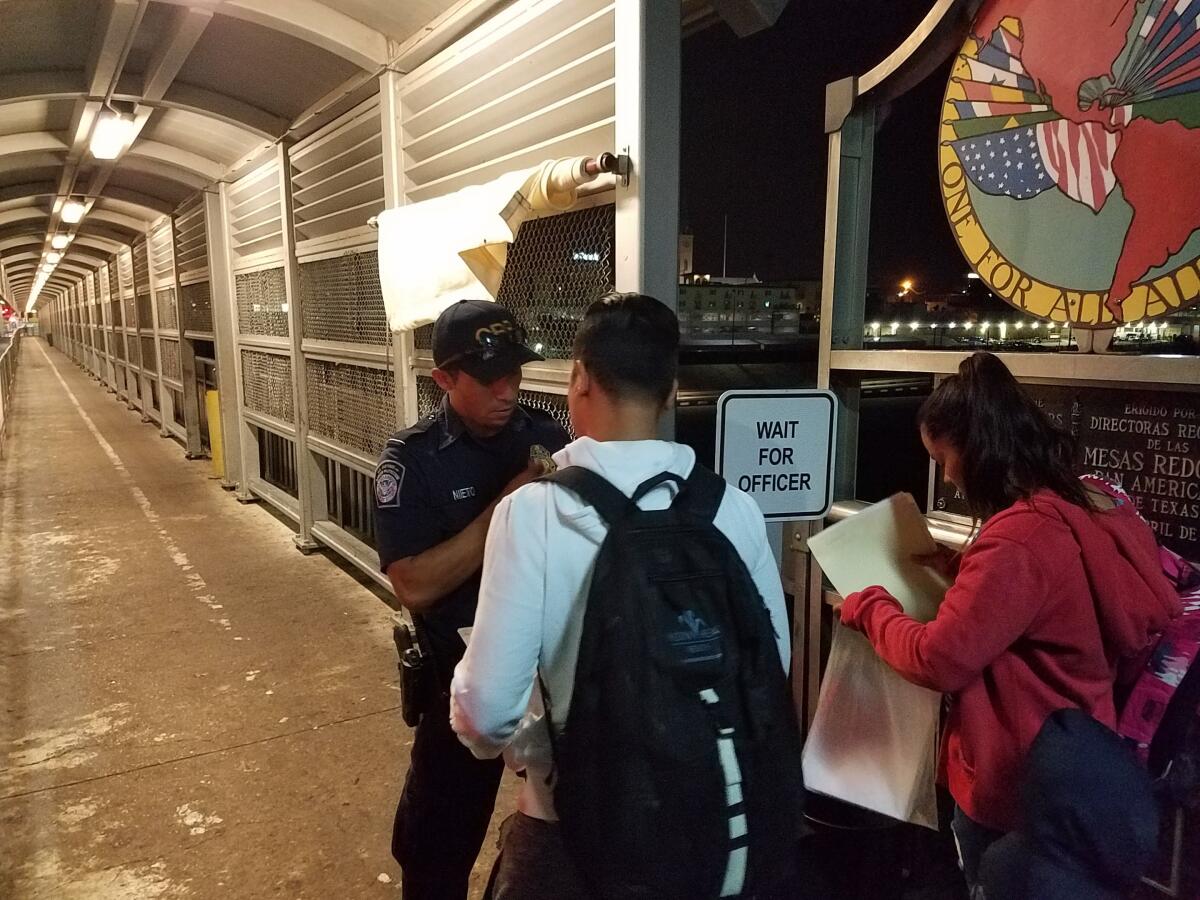

LAREDO, Texas — The woman arrived well before dawn with her 4-year-old daughter for the first full day of hearings Monday as the U.S. government’s new tent court for migrants opened on the banks of the Rio Grande.

Almost immediately, Alejandra Amador, an asylum seeker from Honduras, felt anxious. She didn’t know that the immigration judge would be appearing via video from San Antonio, that this would be the first of several hearings or that she wouldn’t have access to a lawyer.

“Are they going to assign me one?” Amador, 24, said as she waited at 4 a.m. to cross the border bridge from Mexico to Texas for her hearing.

Of 52 asylum seekers scheduled to appear in the Laredo tent court Monday, only half showed up, just four with attorneys, which are not provided in immigration court. Judge Yvonne Gonzalez, who could see the asylum seekers on a television screen in her San Antonio courtroom, ordered the rest of the migrants deported, ending their chances at asylum.

Tent courts are what migrant advocates consider the latest hurdle the Trump administration has added to dissuade asylum seekers from pursuing their cases. Amador and others had already been sent back from the U.S. to Mexico to await hearings under the administration’s Migrant Protection Protocols, also known as the “Remain in Mexico” program. Those arriving at the border already faced long waiting lists imposed by U.S. Customs and Border Protection and more recently the administration’s asylum ban, upheld by the U. S. Supreme Court last week.

Those attending court Monday included not only Central American migrants, but also Cubans and Venezuelans. Some had relatives in Los Angeles, Austin and Miami who arrived in recent years and were allowed to stay legally, before the latest asylum policies took effect.

“It’s more difficult now. I wish I came at a better moment,” Venezuelan asylum seeker John Rondon said as he waited for court Monday.

Rondon, 40, had traveled to the border with 6-year-old daughter Dara hoping to join his mother-in-law, who came to Mississippi last year after receiving a visa.

Homeland Security officials notified Congress this summer that they planned to shift $155 million from disaster relief to expand facilities for Remain in Mexico hearings. Unlike other immigration courts, the tents built in Laredo and Brownsville, Texas, this summer are not open to the public. U.S. Rep. Henry Cuellar, a Laredo Democrat, was allowed to visit that tent court Monday, but The Times was barred from entering by a Border Patrol supervisor who said the court was a “secure area.”

Laura Lynch, senior policy counsel with the American Immigration Lawyers Assn., was also barred from observing Monday’s hearings by Immigration and Customs Enforcement staff after entering the tent complex.

“There’s an operation secrecy surrounding this whole tent court. It’s clearly intentional to keep asylum seekers out of the U.S.,” Lynch said.

Charanya Krishnaswami, Americas advocacy director for Amnesty International USA, said she was also turned away from the Laredo court by Homeland Security police who told her, “This is a zero access facility by order of the president of the United States.” She said migrant advocates have been trying to observe what happens in part because Remain in Mexico is an unprecedented program that requires added oversight.

“A lot can happen in immigration court when observers are not there to ensure there’s due process,” said Krishnaswami, who has attended Remain in Mexico hearings in El Paso and San Diego. “These court proceedings seem to be less and less accessible as more and more people are affected.”

In recent weeks, observers have been prevented from attending hearings at the El Paso courthouse due to lack of space. Hearings at the Brownsville tent court were scheduled to be conducted this week via video by judges in Harlingen and Port Isabel, Texas — an ICE detention center where observers must apply 24 hours in advance to gain access to the video feed.

Lisa Koop, an attorney with the Chicago-based National Immigrant Justice Center, represented four migrants at the Laredo tent court Monday. She said the facility was full of Border Patrol, ICE and contract security guards. She was allowed to meet with her clients for about a half hour before their hearings, she said, but wasn’t allowed to approach other migrants like Amador who didn’t have attorneys. Koop said many had “the red eyes of someone who’s been up for far too long.”

“It was heartbreaking … to see these moms holding their sleeping children, completely exhausted and making decisions that will determine the course of their lives,” she said.

Amador, a single mother, said she fled Honduras because her ex-husband beat and stalked her. She had to take an overnight bus to attend immigration court from Monterrey, where she had settled with her daughter after being returned to Mexico in June.

If the judge didn’t allow them to stay in the U.S., they had nowhere to go in Nuevo Laredo and no transportation back to Monterrey, where they had been staying with a woman in exchange for housekeeping. Amador had packed everything they owned in a small paper bag. She did not have a phone.

“I only have $5 because I didn’t know I would have to go back,” she said.

So far, more than 42,000 migrants have been sent back across the border under Remain in Mexico since the program started in California in January. Many have already abandoned their cases and gone home, afraid to stay in Mexico, where they’re easy targets for kidnappers.

Before court Monday, Honduran asylum seeker Yudy Pagoaga said that days after she and her 7-year-old daughter Allison were returned to Nuevo Laredo in July, they were kidnapped with four other migrants. They escaped and met a local pastor who took them in until their hearing. Pagoaga, 30, a single mother who ran a small store in Honduras, said she fled extortion and gang threats and couldn’t return home.

Of the 26 migrants who appeared at the Laredo tent court Monday, several said they were afraid of returning to Mexico, but the judge cut them off. She referred nine for interviews with asylum officers, which were conducted elsewhere in the tent court complex, according to Yael Schacher, an advocate with Refugees International who attended San Antonio immigration court.

The judge told the migrants to return for their next hearing Oct. 16, and adjourned before noon.

Schacher, who has observed Remain in Mexico hearings at courthouses in El Paso and San Diego, said migrants there were allowed to explain why they were afraid to stay in Mexico. But with the advent of tent courts, she said, “We’re not going to be able to hear people’s stories in court, and the speeded-up process means many more people won’t have attorneys.”

After Monday’s hearing, most of the migrants were released back onto the bridge to Nuevo Laredo. Koop’s clients said they were satisfied with the process, and planned to stay in Mexico and pursue their cases.

“We still expect a positive result,” said Josue, 23, a Honduran traveling with his 21-year-old niece. He asked to be identified only by his first name because he feared for his safety.

Amador, however, was too exhausted. She said she didn’t plan to wait for the next hearing. She was giving up, returning with her daughter to Honduras.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.