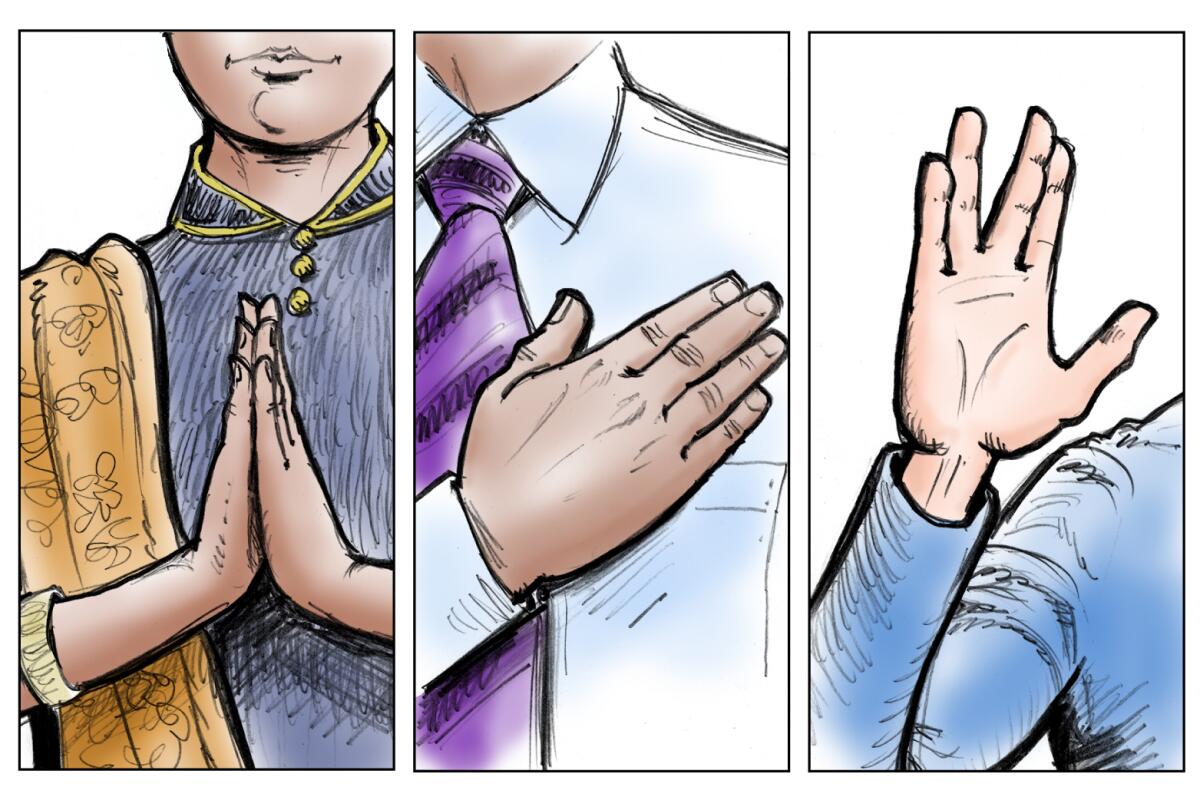

Joined palms, hands on hearts, Vulcan salutes: Saying hello in a no-handshake era

Handshakes? Not advised. Fist bumps? Not recommended. Kisses on the cheek? Absolutely not.

Even elbow bumps are too close for comfort, according to the head of the World Health Organization.

As we enter the era of social distancing, Americans are rapidly reassessing their approaches to the most basic form of social etiquette: saying hello.

It will not be easy: Handshakes and hugs are so ingrained in our culture — a movement that is nearly akin to an automatic reflex — that it seems cold, if not downright hostile, to withhold the gesture, especially in encounters with relatives, friends and even colleagues. The coronavirus pandemic has compelled public health authorities to seriously suggest forms of greeting that avoid contact.

One gesture that WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus recommends is the Hindu greeting of namaste, which is accompanied by placing one’s palms together, fingers pointed upwards and drawing the hands to the heart.

“I like to put my hand on my heart when I greet people these days,” said Dr. Tedros, who is from Ethiopia.

Namaste — sometimes pronounced “namaskar” — means “I bow to the divine in you” in Hindi. In India, as well as in Bangladesh, Nepal, Thailand and other parts of Southeast Asia, the greeting is used to welcome guests, acknowledge strangers and say goodbye.

The actual motion that accompanies the word namaste is called anjali mudra. Anjali means offering.

“It’s a way to acknowledge that the divinity in me honors and sees the divinity in you,” said Suhag Shukla, the executive director of the Hindu American Foundation in Philadelphia. “It’s a healthy greeting that is hygienic and also sends a really powerful message to the world right now. We are so polarized, socially and politically, that it is a great reminder that our actions have an impact beyond our nuclear spaces that we create.”

Many world leaders have ditched the handshake and opted to use that gesture in recent days.

Take Britain’s Prince Charles, who greeted guests that way at the Commonwealth Reception. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has encouraged Israelis to adopt it in order to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus.

But changing habits can be hard. Before President Trump addressed the nation to declare a national emergency Friday, he shook hands with numerous officials and chief executives at the White House. (He did bump elbows with one chief executive, Bruce D. Greenstein of the LHC Group, which provides home health care.)

Then there’s the shaka sign, more commonly known as “hang loose” gesture among surfers, which involves three middle fingers folded down and the subsequent wave of the hand while the pinky and thumb are pointed upward. Its origins are debated, but many Hawaiian natives flash it as a way to say “Hey!” or “Cool!” While seemingly simple, the gesture isn’t entirely casual: It has long been a sign of respect and affection.

Noncontact greetings are particularly difficult for people in parts of Europe and Latin America, where a kiss — or sometimes two or three, on alternating cheeks or into the air — is a common expression of friendliness, even among new acquaintances.

“We’re very affectionate in Colombia,” the country’s health minister, Fernando Ruiz, recently told Caracol News, the national broadcaster. “We like to greet each other with a kiss. That’s great.” But he urged a pause on the practice for at least “three little months.”

Julen Munárriz, a researcher at UCLA’s Department of Biochemistry, is from Spain and is accustomed to greeting and saying goodbye with a kiss on each cheek. In the U.S., he said, this practice is a lot less common, so the recent shift to hand waves and elbow bumps did not feel so different for him.

That is, of course, except among Angelenos with ties to Europe and Latin America. “It’s a bit more complicated in that context,” said Munárriz. “Sometimes I start reaching for a kiss without even realizing it, and then I have to stop myself.”

Recently, some friends began leaning away when he reached out to greet them. It was awkward. “But I think this is a positive change,” he said. “I’m aware that we’re in a critical situation, and this is something that’s necessary to stop the virus from spreading. So I’m happy to do it.”

“Plus,” he added, “I hope this will all go back to normal within months. I don’t think this is going to change our concept of culture.”

People in Muslim majority countries have a wide range of meet-and-greets.

In Iran, one popular greeting is to lay kisses on cheeks. In more conservative parts of the country, it is more common to place the palm of the hand on the heart, while tilting and bowing.

Muslims have arguably been placing their right hand over their hearts “since the time of prophet Muhammad in the 7th century,” said Craig M. Considine, a lecturer at Rice University whose research focuses on Islamophobia and Christian-Muslim relations.

“An epidemic like this can really bring us to our humanity,” he said. “In a way, it eliminates all of these stereotypes that we have about how certain groups behave the way they do. It’s hygienic but, more importantly, it’s also a sign of respect and endearment.”

Earlier this week, Sweden’s ambassador to Kosovo was photographed placing her right hand over her heart. In Europe, the move to use this gesture in place of handshaking is noteworthy, given that Muslims have been ostracized for doing just that.

In 2018, for instance, a Swedish Muslim woman placed her hand over her heart instead of extending it to a job interviewer. The interview was terminated. The woman filed a successful discrimination complaint.

Earlier, in 2016, Switzerland suspended the naturalization process for the family of two teenage Muslim brothers who declined to shake hands with female teachers. In 2018, France denied citizenship to an Algerian woman who decline to shake the hand of a male official during a naturalization ceremony.

Bowing, a gesture with roots in Asia and Europe, has also been suggested. This gesture can involve simply lowering the head or more elaborate bending from the torso. Like some hand gestures, this act is not reserved for greetings, but can also be employed to express respect, gratitude or remorse.

While some may look toward traditions and practices that span hundreds of years in countries that sit thousands of miles away, one option for non-physical contact that hits closer to home is the Vulcan salute: the hand gesture popularized by “Star Trek.”

For decades, millions of fans of the TV series have used this gesture, which consists of raising one’s hand, with space between the middle and ring fingers, and the index finger and the thumb.

As it turns out, the inspiration for that gesture stems from Judaism. Specifically, when a person makes that gesture, it is in the shape of the Hebrew letter “shin,” which represents one of the first letters of God’s name.

The risk in many of these alternatives is that of causing offense — or appropriating someone else’s culture. For that reason, many Americans might find the simple wave the best way to greet someone without touching them.

Shukla, the executive director at the Hindu American Foundation, said the fine line between appropriation and appreciation is intent.

“As long as people have an intent of looking out for the well-being of others and being mindful of the germs we are spreading, then there is the right intent,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.