Deleting Facebook, downloading VPNs: How Hong Kongers are preparing for a draconian law

HONG KONG — As a veteran political cartoonist, Justin Wong is rarely at a loss for the right image.

But China’s move to impose new national security powers over Hong Kong reduced his latest work to two simple words against a white backdrop: “I fear.”

Wong, an illustrator for the Ming Pao, a newspaper with a six-decade tradition of journalistic independence, has long used his platform to defend Hong Kong’s autonomy and satirize Beijing’s leaders.

The new law, if applied as arbitrarily as it is across the border in mainland China, is seen by many as a “death knell” for the former British colony’s freedoms, placing Wong and others like him at risk for simply expressing their opinions.

“I criticize the government every day,” said Wong, 46. “Now I have to think about what I can say and what’s safe.”

There is no modern precedent for what Hong Kong could soon experience. Never has a society so intertwined with the global economy and accustomed to the same sort of freedoms and standards of many Western nations been integrated with an authoritarian communist system and stripped of rights.

The much smaller territory of Macao passed similar national security legislation in 2009, but the gambling mecca doesn’t share the same political ferment.

Whether Hong Kong ends up looking more like Singapore, a financial hub where speech and public assembly is curtailed, or Tibet, a Chinese province under oppressive state control, remains to be seen. Details of the law approved Thursday by China’s rubber-stamp National People’s Congress have yet to be revealed.

Hong Kongers are now frantically making plans for a new reality — scrubbing their social media feeds of offending posts, downloading VPN software to hide online activity and researching what it takes to move abroad.

Wong He, a comedian, TV star and former policeman who has increasingly run afoul of the city’s government for his support of the protests, received a call from his attorney the day after the law was introduced advising him to do two things: consider emigrating and deleting his social media accounts so that his followers could not be found to have liked, shared or commented on his anti-government posts. He admitted that was likely futile; things don’t just disappear from the internet, but he did it anyway.

“I’d feel guilty if anyone got in trouble because of me,” said the 52-year-old actor, who posted a video explaining how to delete a Facebook account.

Trust in the Police Force has deteriorated after months of protests. Now it’s seen as just the Chinese government’s tool of oppression, ex-cop says.

Wong He, like many Hong Kongers, knew there would come a day when the firewall between Hong Kong and the mainland would likely topple — just not so soon.

China was supposed to preserve Hong Kong’s way of life for 50 years after a “one-country, two-systems” arrangement with Britain took effect in 1997. It’s why Hong Kongers have many of the ordinary freedoms people in the U.S., but not China, enjoy, including an uncensored internet and an independent press.

Critics say the new national security law, expected to be implemented later this summer, effectively marks an early end to that experiment — a denouement brought on by Beijing’s desire for more control and the fierce resistance it inspired in a series of mass protests in recent years.

None were more violent and widespread than those seen during the past year, which were sparked by Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s failed bid to introduce an extradition law with China that would have exposed Hong Kongers to the arbitrary laws of the mainland, much like the national security law.

Hong Kong is consumed today by the same anxieties that marked the lead-up to 1997 — only this time with the fresh wounds of last year’s protests.

“There were dire predictions in the mid-1990s that as soon as the handover took place, the newspapers would stop being able to mock the government and that everything would change,” said Jeffrey Wasserstrom, a historian at UC Irvine and author of “Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink.”

Hong Kong is also caught in the middle of a rapidly escalating geopolitical standoff between the U.S. and China, further ratcheted up Friday by President Trump’s announcement that he would strip the territory of its special trade privileges.

The very thing that has made Hong Kong so vital for more than a century — its role as a bridge between China and the West — is now its greatest vulnerability in the eyes of Beijing, which views dissent in the international outpost as a threat to its sovereignty.

“Hong Kong is the new Berlin in a new Cold War,” said a 20-year-old protester, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he feared he could be arrested for his role in demonstrations.

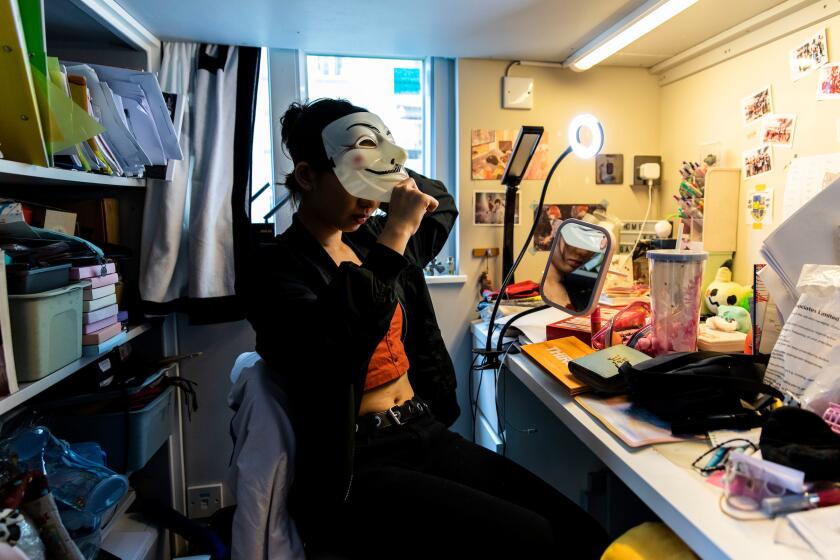

The student studying law at the Chinese University of Hong Kong helps run a Facebook group, with anonymous membership, created last year as a means to oppose the extradition bill that sparked the city’s protests. It’s now changed focus to oppose the national security law, which has hardened the members’ stance. Their masked ire is now directed at leaders in Beijing, not Hong Kong, and they advocate independence — one of the chief violations of the new national security law.

“As long as Hong Kong people stay determined and resist, I believe we can demonstrate our value to the free world as a front in the fight against the Chinese Communist Party,” the student said.

Hong Kong’s government has tried to assuage fears that the Chinese law will stifle many of the freedoms residents of the city of 7 million are used to — at the same time introducing a local law that would make it illegal to disrespect China’s national anthem.

In an open letter published Friday, Chief Executive Lam said the city’s laws were inadequate for dealing with rioters and foreign interference. She said Beijing’s national security law will bring stability to Hong Kong and would be narrowly applied.

“It will only target an extremely small minority of illegal and criminal acts and activities, while the life and property, basic rights and freedoms of the overwhelming majority of citizens will be protected,” Lam wrote. “Citizens will continue to enjoy the freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of demonstration, of procession, and to enter or leave Hong Kong in accordance with the law.”

Lam noted that every country has laws protecting national security, but legal experts say many of them are applied in societies with a separation of powers. In China, one-party rule allows national security legislation to target journalists, human rights activists and lawyers such as the late Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo, who was jailed for inciting subversion.

“People in China are subjected to an arbitrary system of justice designed to silence opposition,” said Sharron Fast, a legal expert at the University of Hong Kong’s Journalism and Media Studies Center. “With the mass detention of the Uighur population, the forced disappearance of human rights lawyers and religious groups, I think it’s very clear that the criminal justice system in China is not one that can reliably support fundamental rights.”

Months of protest have driven many Hong Kongers to consider moving abroad and rekindled memories of the 1990s, when hundreds of thousands fled out of fear of communist rule.

Fast, a Canadian, said professionals like herself face an uncertain future in Hong Kong. Her teachings on international standards of law and journalism to students, including many from the mainland, appear increasingly anathema to China’s vision for the territory at its doorstep.

“I feel like I’m facing extinction,” she said. “My job could be criminalized. I’ve spent 15 years reaping the benefits of this gracious, freedom-loving place. I don’t want to abandon Hong Kong, but it’s something people have to consider.”

In many ways, the culture of official impunity that critics say the national security law will invoke was previewed most recently with the April arrests of 15 high-profile democracy figures and the release of a report earlier this month by the police watchdog absolving the police force of abuse during protests despite widespread evidence to the contrary.

Hong Kong’s business community, which showed alarm over the extradition bill last year, has been more supportive of the national security law despite the perceived threat it poses to the independence of courts and the city’s standing as a global financial center. Many feel the pain inflicted by Washington’s punitive actions over the law will be short-lived given the entrenched financial interests U.S. companies maintain in Hong Kong.

Business leaders hope the law will bring a final end to the protests, which have alienated many well-to-do Hong Kongers, and kick-start an economy battered by a trade war and pandemic (Hong Kong has fared extraordinarily well with only four deaths linked to COVID-19).

“Hong Kong will always be a special place,” said Allan Zeman, the billionaire founder of the Lan Kwai Fong Group. “I was worried in 1997 too. But I can guarantee nothing will change. It will be business as usual. China needs Hong Kong to do business with the rest of the world.”

If business does rebound, it will still have to contend with a protest movement that has reignited in recent weeks, said Gwyneth Ho, a democracy activist and former journalist who was beaten during a politically-motivated gang attack on innocent subway passengers last July.

The 29-year-old said she’s inured to the dangers of resistance, but remains hopeful Hong Kongers can blunt the effects of the national security law as long as the territory’s foreign press corps, deep ties to foreign governments and civil society organizations overseas remain.

“That’s the thing activists in China didn’t have,” Ho said. “We are an international city. Nothing that goes on here will go unseen or unheard like in the mainland.”

Times staff writer Pierson reported from Singapore and special correspondent Tang from Hong Kong.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.