Police detain prominent law professor and government critic as China’s crackdown continues

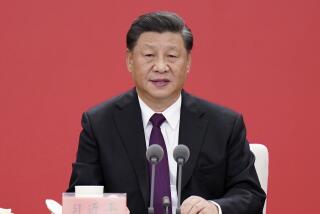

BEIJING — Tsinghua University law professor Xu Zhangrun, one of China’s few remaining outspoken critics of President Xi Jinping and the communist government, was taken from his home in Beijing by police on Monday morning.

Close friends of Xu’s who spoke with his family confirmed that he had been arrested and that they did not know where the police had taken him.

About 20 police officers surrounded Xu’s home while more than 10 others entered, searched the residence, confiscated his computer and then took Xu away, according to a statement from friends of Xu, which has been widely circulated among Chinese activists.

Police did not make any public statement about Xu’s arrest or any charges.

The Chinese legal expert had taught jurisprudence and constitutional law at Tsinghua, one of China’s most prestigious universities, but was suspended in 2019 after publishing a series of essays that criticized Xi’s alteration of the Chinese Constitution to remove presidential term limits.

Xu’s detention is the latest amid a crackdown on dissent and free speech in China that has especially targeted intellectuals and those who stray from the Communist Party narrative of state-led victory over the country’s coronavirus outbreak. Room for dissent continues to shrink under Xi’s government, as those who voice challenges to the party’s authority are silenced one by one.

A growing number of professors in China have been punished for ‘improper speech.’ Some are reported by students, harking back to the Cultural Revolution.

Novelist Fang Fang, whose published diary depicts ordinary people’s suffering during lockdown in the city of Wuhan and seeks accountability for government missteps, has become the target of nationalistic attacks with implicit state support. Several professors who wrote essays supporting Fang Fang have been placed under investigation or fired and stripped of their Communist Party membership.

Ren Zhiqiang, a real estate tycoon with powerful political connections — his father was among the generation of communist revolutionaries who founded the People’s Republic — also disappeared this year after he wrote an essay calling Xi a “clown” over his handling of COVID-19. The party later announced that Ren was under investigation for “serious violations of law and discipline.”

Several citizens who tried to report on the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan have also been detained. They include lawyer Chen Qiushi, Wuhan resident Fang Bin and former CCTV employee Li Zehua, who reappeared in April after disappearing for two months. Li gave a video statement in which he said that the police had acted “civilly and legally,” demonstrating care for him while he was in detention and quarantine.

The others remain missing.

The coronavirus. A deadly building collapse. Political cover-ups. All poke holes in China’s desired image as a wealthy superpower poised to lead the world.

This year, human rights lawyer and activist Xu Zhiyong (no relation to Xu Zhangrun) was arrested in southern China after he called for Xi’s resignation online. He had been part of a circle of dissidents, lawyers, intellectuals and civil society members who met in the port city of Xiamen in December to discuss how to build citizenship and rule of law in China.

More than a dozen attendees of those meetings have been detained or called to court, while others remain in hiding.

Others who have been jailed, vanished, put under house arrest or pressured into silence through threats to their families, jobs and lives in recent months include lawyers, poets, petitioners, COVID-19 survivors and their families.

Xu Zhangrun had been under pressure since 2018, long before the pandemic, for penning pointed criticisms of China’s current political state. His essays are both literary and analytical, at once striking at the heart of party authority and offering policy suggestions for change, all with a poetic flourish.

A sweeping security law signals Beijing’s determination to crush pro-democracy protests at the risk of deepening its rift with the U.S. It is a bold strategy from Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

In his first 2018 essay, titled “Our imminent fears and hopes,” Xu criticized Xi’s erasure of term limits, suppression of intellectuals, overspending on foreign aid while inequality worsened at home, and pulling China back into a period of isolationism and personality cult-led politics.

Xu called for officials to disclose their personal assets and for an end to the system that provides access to better healthcare, vacation resorts and safe food for high-level cadres.

After that essay, Xu was suspended from teaching, put under multiple periods of house arrest and blocked from leaving China, according to his friends. But he continued to write.

In February, at the height of China’s coronavirus outbreak, as calls for freedom of speech swept the nation after a whistle-blowing doctor’s death, Xu wrote “The angry people are no longer afraid,” an essay lambasting Xi and the “ethically bankrupt” Communist Party for prioritizing their power above Chinese citizens’ lives.

“It is a system that turns every natural disaster into an even greater man-made catastrophe,” Xu wrote. “The coronavirus epidemic has revealed the rotten core of Chinese governance.”

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

After that essay, Xu was again placed under house arrest and periodically cut off from the internet. He was aware of looming imprisonment: “This may well be the last thing I write,” he noted in the essay. “But that is not up to me.”

He was able to meet with friends and fellow professors for meals occasionally, according to his colleagues.

In May, just before the national political meetings in Beijing, Xu wrote a final essay titled “China, a lone ship on the vast ocean of global civilization,” lamenting the country’s continued slide toward totalitarianism and calling again for accountability, release of detained journalists, free speech, protection of property and transparency.

“Enough with this mold-infested god-making movement, this shallow worship of leaders,” he wrote. “Enough with these seven years of absurdity and confusion, ... these 70 years of mountains of corpses and oceans of blood....”

He signed it: “With outrage, worry and sorrow.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.