The comfort of cash in a time of coronavirus

WASHINGTON — At Sunshine Ace in Naples, Fla., signs have been put up to encourage contact-less payments during the coronavirus crisis. Employees at the chain of hardware stores constantly wipe down the touch pads of debit card readers, and at each checkout counter the chain has installed plexiglass shields. When Michael Wynn, Sunshine’s third-generation owner, checked his books for June, payments in cash had dropped slightly since the start of the pandemic. It looked like another sign of the steady demise of cash.

Yet that is not the whole story. The resilience of paper money — again illustrated during the pandemic — means the hardware chain and many other retailers like it cannot plan to get rid of bills and coins entirely. Customers at Ace’s stores in poorer parts of southwestern Florida still like to pay for paint and hammers with cash. At Ace’s Port Charlotte branch, cash was 19.3% of sales in June, compared with an average of 13.3% for all its stores. Parts of Florida, which on Tuesday reported 133 coronavirus deaths (a one-day record for the state), have returned to lockdown. But Sunshine Ace has stayed open.

Wynn’s customers are showing what financiers would call a higher “liquidity preference” — they’re borrowing what they can and holding on to their cash in a time of uncertainty. Early in the pandemic, he says, customers also loaded up on propane and water, the way they would if preparing for one of Florida’s frequent hurricanes. As storms approach, the state tells its citizens to have cash available.

“I think it’s a form of comfort,” says Wynn, “because those are typically things we’ve done for our families — like taking out cash.”

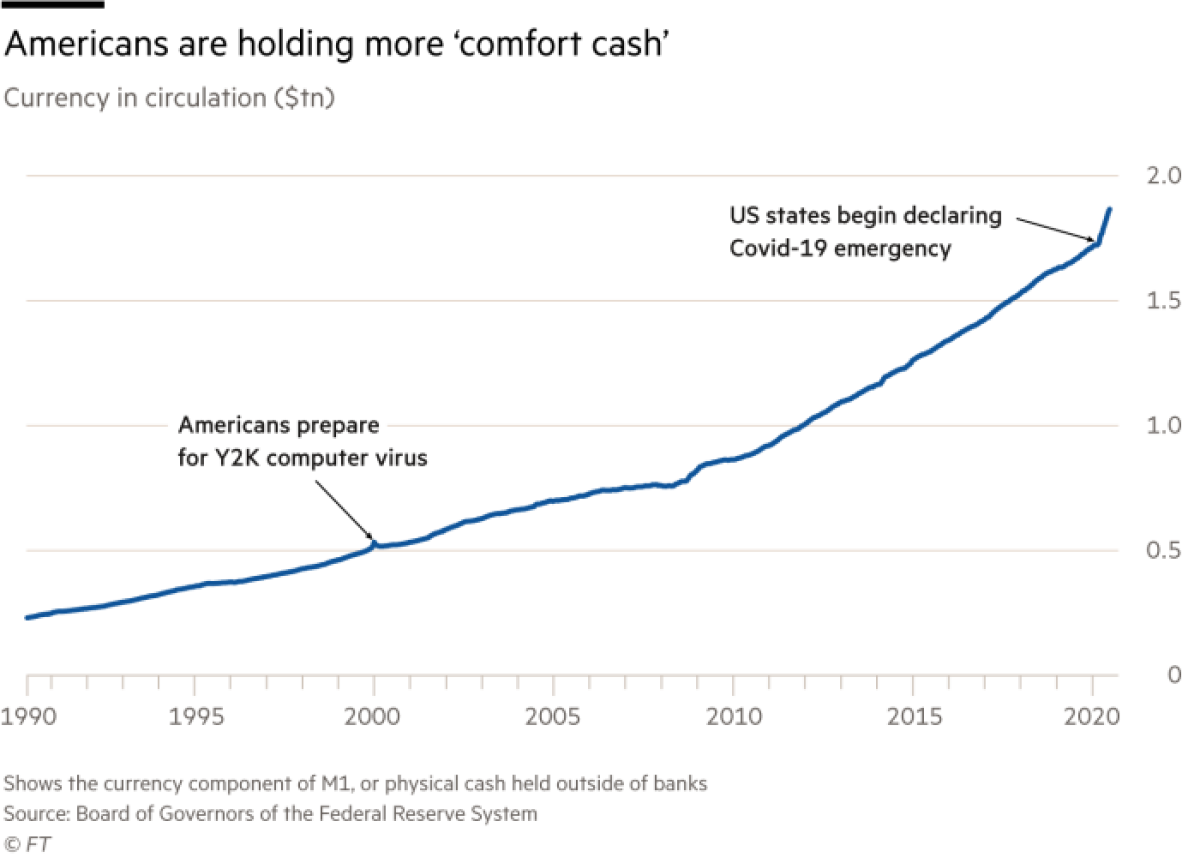

Retail surveys and data from the Federal Reserve support Wynn’s theory. Cash use at the till has declined slightly during the pandemic, as consumers accelerate the shift to electronic payments. But just like the period before a natural disaster, there has been a spike in cash withdrawals in the U.S.

Americans are using less cash but they are holding more, which presents a challenge for the Federal Reserve and other central banks around the world. They have to maintain a vast network of secure printers and depots to deliver cash to where it is needed. As people use less cash, each piece of this infrastructure becomes more expensive to operate. But central banks will not be able to wind it down completely, for two reasons. First, the poor are more likely to still use cash, exacerbating the “digital divide.” And second, in a crisis, everyone wants a fistful of dollars.

“[Cash is] the one asset that people are pretty confident isn’t going to lose value,” Eric Rosengren, president of the Boston Fed, said in March. “And so people are deciding they’d much rather hold more of their assets in cash.”

Demand for paper

In normal years, the Fed’s weekly measure of currency in circulation is metronomically cyclical. Cash in hand peaks in the last week of December, as people give gifts of crisp dollars in envelopes. Then it drops again in January, as the dollars get deposited. As the coronavirus crisis began to intensify from March, currency held outside of banks began to shoot up. At the end of June it was 13% higher than the same time last year, and up 8% since the end of February alone, the most dramatic move since the Fed’s data began in 1975.

Fed policymakers say this behavior is not evidence of a lack of faith in banks, and that there is no danger that an ATM will fail to produce bills. In March, Patrick Harker, president of the Philadelphia Fed, said, “We have more than enough capacity to hand over demand,” adding that demand had increased.

The Fed is watching currency orders from banks closely and as always has a stock of bills ready, according to its board of governors in Washington. In June, the Fed cautioned banks that consumers were depositing less change and the U.S. Mint had been producing fewer coins as it carried out social distancing at its plants. As a result, the central bank is currently limiting its distribution of small change to banks.

Rosengren says that a small number of wealthy people withdrew large amounts of cash in his district early in the pandemic, as an unimpeachable hedge when markets for even safe financial assets, like treasuries, were behaving strangely. Mostly, though, he believes that the withdrawals were just precautionary decisions by ordinary Americans.

Bill Maurer, an anthropologist at UC Irvine who studies payments, calls the decision to withdraw cash “contextually rational.”

It’s not that people are worried about how the Fed distributes cash, he says. It’s that, as in any disaster, people are worried about everything else — the electrical grid or the mobile network.

Frederick Wherry calls the phenomenon “comfort-food hoarding.” A sociologist at Princeton University and an advisor to the Boston Fed, he says hoarding can be a response to feelings of helplessness or isolation.

When people eat real comfort food, he adds, “they are just trying to maintain a sense of stability and trying to have an object that feels familiar and stable. And to a large extent, paper money has been that.”

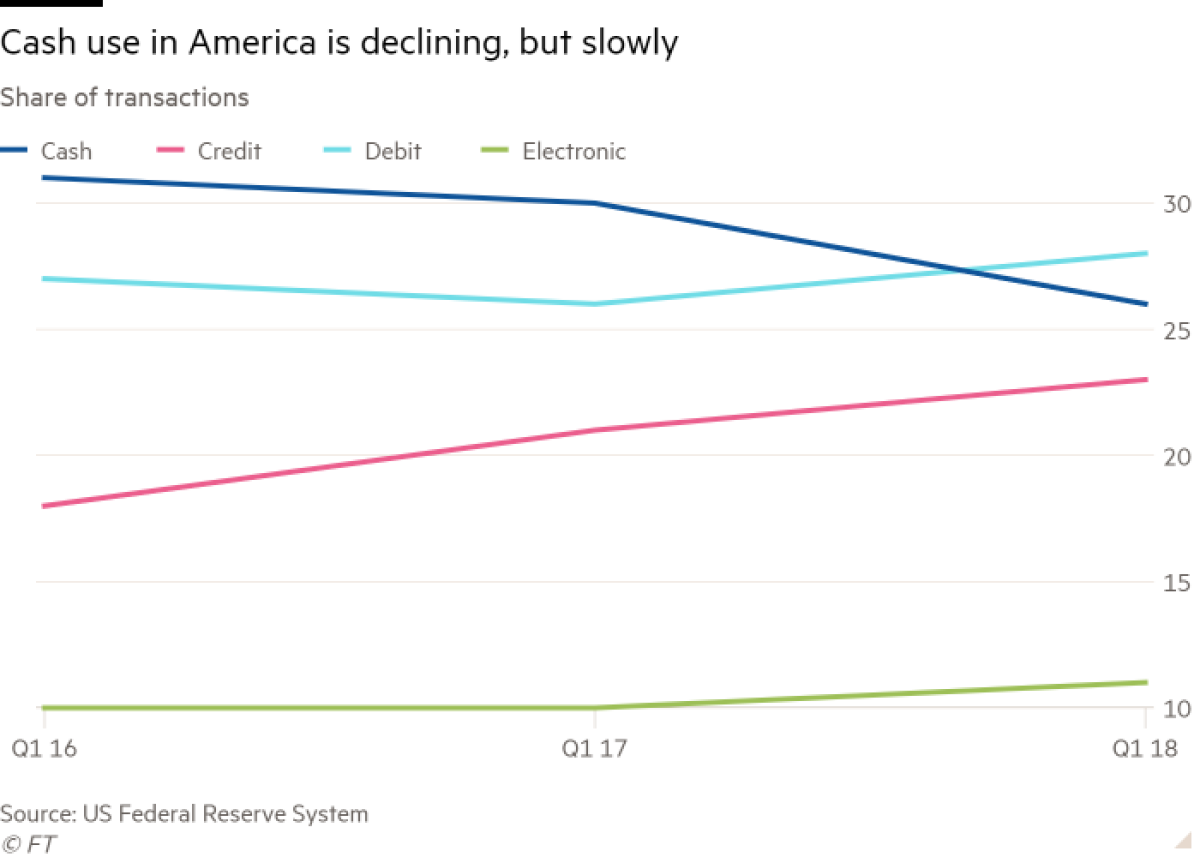

Diary of payments

Every year the Fed asks a group of about 3,000 Americans to keep a diary of how they pay for goods and services. According to those accounts, the use of cash has been steadily dropping in the U.S. — to 26% of transactions in 2018, down from 31% in 2016.

There are conflicting reports of whether the pandemic has accelerated that process. At the end of June, a survey by RTi Research showed that 32% of Americans reported using less cash in the previous two weeks. That is down from a recent high of 38% at the end of May, but up from 27% in mid-March. An April survey of firms by 451 Research, an arm of S&P Global Market Intelligence, showed 31% of customers using less cash than before the pandemic, but 19% using more.

“Cash is dying a very slow death,” says Jordan McKee, an analyst at 451. He adds that it is “a death we won’t see in our lifetimes.”

The Fed’s diary data support the anecdotal sense from retailers that poorer, older Americans are more likely to pay with cash. Its basic obligation to provide cash has not changed. Central banks still have to provide all citizens with a way to make payments, and they have to be ready to react to spikes in demand for physical currency. Complicating those plans is the new era of social distancing at workplaces, such as the Fed’s cash-processing depots where key workers move cash in and out of armored vehicles.

Regardless of any fall in the use of cash, central banks in many developed countries will not see a proportional reduction in the costs associated with the infrastructure of depots and employees engaged in moving paper around a country. The essential plumbing does not get any less complicated or expensive to operate.

In Britain, the Bank of England and a group of commercial institutions are investigating how to make it cheaper for banks and stores to use cash, after an independent review found there was little point to shoring up the country’s disappearing ATM system if stores were going cashless. A similar project is underway in New Zealand.

Other countries are looking to Sweden. Cash use there is down to 15% of transactions, and the Riksbank has become a leader among central banks in developing a digital currency. But Sweden also has recognized that it cannot let its ability to move cash around atrophy completely. In April, a Riksbank report pointed out that “it is difficult to get cash to work in the way it is intended in times of heightened alert and war, if cash is not used to a certain extent in normal times as well.”

Money factories

The Miami branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta sits west of the airport, across the street from the four golf courses of the Trump National Doral. To even get to the parking lot, a visitor has to follow a procedure similar to what it takes to enter a U.S. embassy in a hostile country.

Inside the branch is a warehouse full of stacks of dollars. Asked how much money is piled up, a Fed employee says: “I would go with ‘a lot!’,” adding: “We don’t talk about specifics.”

The cash is distributed and moved via armored trucks from the U.S. Treasury’s printers to one of 27 depots like the one in Miami, then to banks, then back to the depots, as banks take in cash deposits. Bays inside the Miami depot open for the trucks returning from commercial banks. The bills get wheeled into rooms with machines built by a German company, Giesecke & Devrient. These count and examine 40 bills a second. Old bills are shredded immediately.

Together, the Fed’s cash depots move 33 billion bills a year. But the one in Miami looks less like a bank and more like a factory.

“Cash is the payment vehicle that’s most often taken for granted,” says Mark Gould, head of the Fed’s Cash Product Office. “You know, when people go to the ATM, there’s generally money there.”

“When I hand you a $10 bill, hey presto, $10 of value has been transferred,” adds Maurer, the anthropologist. “Now of course we know there’s an enormous infrastructure behind that act, a set of systems that give the dollar value and that also allow it to settle at face-value level at par. That’s all the work of the Fed and the Cash Product Office. But that’s invisible to us.”

Disaster management

That work becomes more difficult during a natural disaster. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the Atlanta Fed realized that its New Orleans branch, on relatively high ground on historic St. Charles Avenue, had become stranded and unable to distribute cash. The Fed introduced a system that allowed it to hand off orders to adjacent branches if any became unreachable. The Houston branch of the Dallas Fed replicated the system during Hurricane Harvey in 2017.

Just two weeks after Harvey came Hurricane Maria. On the Monday after Maria made landfall, devastating the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico, including its electricity network, cash orders from the island were up more than 800%. To supply enough small bills for transactions, the Fed’s Cash Product Office needed an airlift.

Commercial flights to the island were filled with humanitarian supplies, so the Fed had to charter its own secure flights to get cash packs to San Juan, the capital. The Cash Product Office was in constant contact with armored carriers on the island — transporting the bills that were too heavy for a helicopter — to know which roads were still passable.

Other central banks also have to respond to hurricanes. In 2017, Banco de México announced “Plan Billete,” an agreement with the country’s commercial lenders. The central bank owns and operates two Bombardier aircraft, and within 48 hours of an earthquake or an extreme weather event it can deliver cash anywhere in the country, along with telecommunications and point of sale equipment that can both distribute cash disaster benefits, and offer access to commercial accounts. Several central banks in Asia have looked into Plan Billete as a model.

Severe hurricanes are more regularly making landfall. And planners are already looking at what it means for the Fed and its cash flow challenge if such events become even more common as a result of climate change. “I think one of the questions that we don’t know the answer to is, how will storm patterns change,” says Gould.

Back in Florida, Amanda Burke, a manager at a Sunshine Ace store in San Carlos, says that when her electronic payment systems briefly went down after Hurricane Irma in 2017, some people were reluctant to pay with cash. Burke’s customers were saving their dollar bills, she suspects, in case they needed them for food.

Her experience is similar to that of millions of people across the U.S. during the pandemic: they want cash, but they don’t necessarily want to use it.

Holding on to a stack of bills, says Maurer, is “the recognition that in a pinch I can use cash and it will work with anybody. I don’t need a point of sale terminal. I don’t need to have [payment apps] PayPal or Venmo or Square. I can just go next door and say, ‘Hey, I’m desperate for toilet paper. Here is a $5 bill.’”

© The Financial Times Ltd. 2020. All rights reserved. FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.