Civil rights icon John Lewis remembered in his hometown

TROY, Ala. — Civil rights icon and longtime Georgia Rep. John Lewis, in the rural Alabama county where his story began, was remembered Saturday as a humble man who sprang from his family’s farm with a vision that “good trouble” could change the world.

The morning service in the city of Troy in rural Pike County was held at Troy University, where Lewis would often playfully remind the chancellor that he was denied admission in 1957 because he was Black, and where decades later he was awarded an honorary doctorate.

Lewis, who became a civil rights icon and a longtime Georgia congressman, died July 17 at the age of 80.

Saturday morning’s service was titled “The Boy from Troy,” the nickname the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave Lewis at their first meeting in 1958 in Montgomery, the Alabama capital. King had sent the 18-year-old Lewis a round-trip bus ticket because Lewis was interested in trying to attend what was then an all-white university in Troy, just 10 miles from his family’s farm in Pike County.

It was the first of days of memorials and services for Lewis.

On Sunday, his flag-draped casket is to be carried across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., where the one-time Freedom Rider was among civil rights demonstrators beaten by state troopers in 1965. He also was to lie in repose at the state Capitol. After another memorial at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, where he will lie in state, funeral services will be held in Georgia.

In a 2018 episode of PBS Kids’ series “Arthur,” civil rights leader John Lewis guest-starred as himself to encourage its aardvark protagonist to political action.

At the Troy University service, his brothers and sisters recalled Lewis — who was called Robert, his middle name, at home — as a boy who practiced preaching and singing gospel songs to the farm animals.

“I remember the day that John left home. Mother told him not to get in trouble, not to get in the way ... but we all know that John got in trouble, got in the way but it was good trouble,” his brother Samuel Lewis said.

“And the troubles that he got himself into would change the world,” the congressman’s brother said.

Lewis’ casket was in the university’s arena where attendees were seated spaced apart and masks were required for entry.

“The John Lewis I want you to know is the John Lewis who would gravitate to the least of these,” another s brother Henry Grant Lewis said, a Biblical reference to Jesus’ instructions to aid those in need.

On the day Lewis was sworn in to Congress they exchanged a thumbs up, his brother said. He later asked Lewis what he was thinking when they did.

“He said ‘I was thinking this is a long way from the cotton fields of Alabama,’” Henry Grant Lewis recalled.

Those cotton fields were in then-segregated Pike County, where Lewis winced at the signs designating “whites only” locations.

Rep. John Lewis, 80, an associate of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in the civil-rights movement and congressman from Atlanta, died Friday of cancer.

At his 1958 meeting with King, the Rev. Ralph Abernathy and civil rights lawyer Fred Gray, Lewis talked about the possibility of a lawsuit to try to integrate the University at Troy, Gray recently recalled. The lawsuit ultimately did not happen because of concerns about the likely retaliation his parents would face in the majority-white county.

“The fire inside John to do something about segregation continued to burn,” Gray said. “Even before he met Dr. King, he was interested in doing something about doing away with segregation. And he did it all his life.”

Lewis was one of 10 children born into a sharecropping family. His parents saved enough money to buy their own farm where the Lewis children worked the fields and tended the animals. A young Lewis was less fond of field work — often grousing about the grueling task — but eagerly took on the job of tending the chickens while practicing preaching.

“He had a way of throwing them corn while he was preaching,” younger sister Rosa Tyner remembered.

In his autobiography, “Walking With the Wind,” Lewis described how as a youngster he longed to go the county’s public library but wasn’t allowed because it was for whites only.

“Even an eight-year-old could see there was something terribly wrong about that,” Lewis wrote.

He would eventually apply for a library card there, knowing he would be refused, in what he considered his first official act of resistance to racial apartheid.

In 1955, he heard a new voice on the radio: King, who was leading the Montgomery bus boycott about 50 miles away.

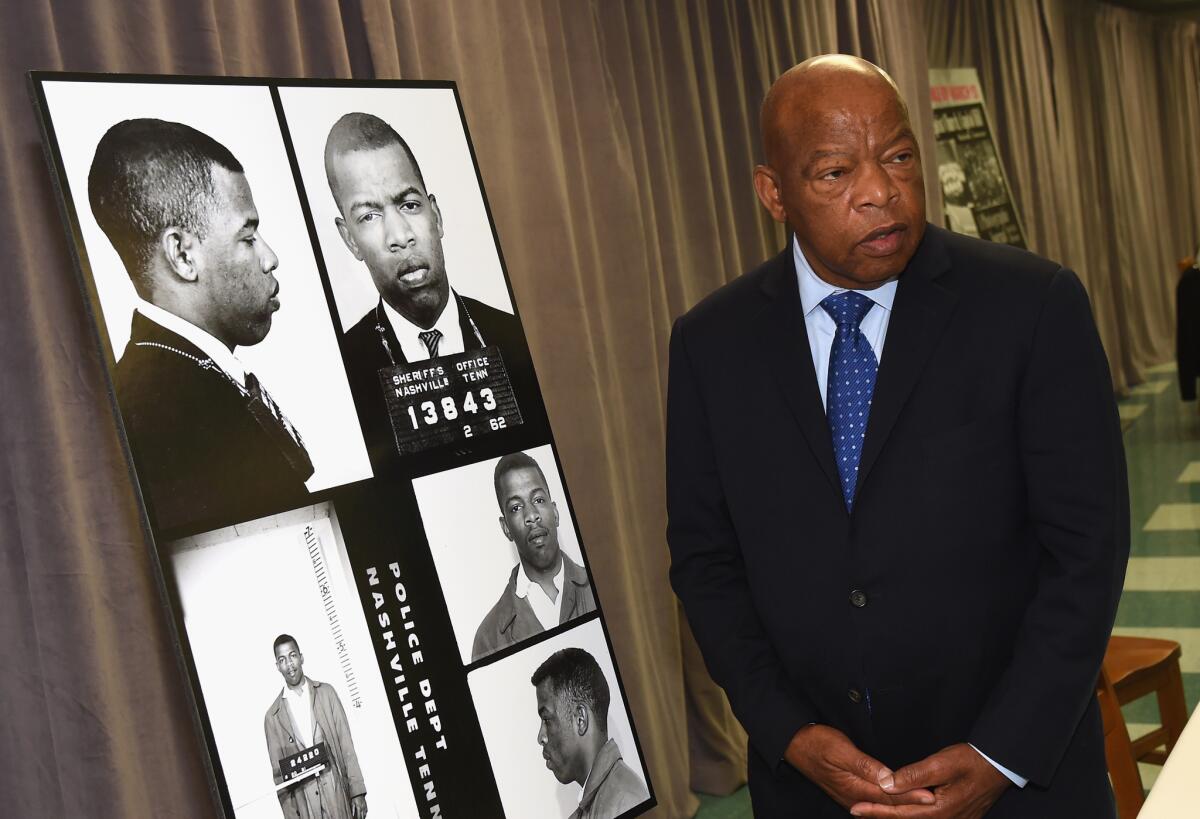

Lewis became a leader of the Freedom Riders, often facing violent and angry crowds, and was jailed dozens of times. In 1961, he was beaten after arriving at the same Montgomery station where three years earlier he had arrived to meet King. In 1965, his skull was fractured on the bridge in Selma in the melee that became known as Bloody Sunday.

His parents and siblings watched the news footage of the Selma beatings, worried that he would become the next civil rights martyr.

The Troy public library now has a sign outside honoring Lewis. Students at the university he wasn’t allowed to attend now study his life and work.

Last year, Lewis announced he had been diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Tyner said that about a week before his death she asked him about possibly seeing another doctor.

“He said, ‘No, I’m at peace. I’m at peace and I’m ready to go,’” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.