Proposed limits on filming police spark uproar in France

PARIS — French activists fear that a proposed new security law will deprive them of a potent weapon against police abuse: cellphone videos.

A bill to restrict images of police has created an uproar in France, with critics saying that it threatens efforts to document police brutality, especially in impoverished immigrant neighborhoods.

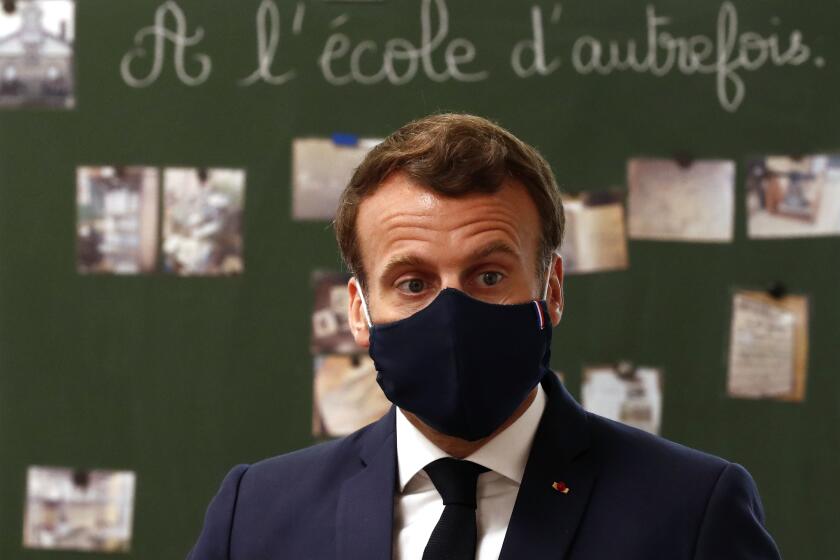

French President Emmanuel Macron’s government is pushing the security bill, which among other provisions makes it illegal to publish images of police officers with intent to cause them harm. Critics fear the new law could hurt press freedoms and make it more difficult for all citizens to report on police brutality.

“I was lucky enough to have videos that protect me,” said Michel Zecler, a Black music producer who was beaten up recently by several French police officers. Videos of the beating, first published Thursday by French website Loopsider, have been seen by more than 14 million viewers, resulting in widespread outrage over police actions.

Two of the officers are in jail while they are being investigated. Two others, also under investigation, are out on bail.

The draft bill, still being debated in parliament, has prompted protests across the country called by press freedom advocates and civil rights campaigners. Tens of thousands of people, including the families and friends of those killed by police, marched Saturday in Paris to demand rejection of the measure.

Under pressure from police, the French government has backed away from a ban on chokeholds during arrests

“For decades, descendants of post-colonial immigration and residents in populous neighborhoods have denounced police brutality,” Sihame Assbague, an antiracism activist, told the Associated Press.

Videos by the public have helped show to a wider audience that there is a “systemic problem with French police forces, who are abusing, punching, beating, mutilating, killing,” she said.

Activists say the bill may have an even greater impact on people other than journalists, especially those of immigrant origin living in neighborhoods where relationships with the police have long been tense. Images posted online have been key to denouncing cases of officer misconduct and racism in recent years, they argue.

Assbague expressed fears that, under the proposed law, those who post videos of police abuses online may be put on trial, where they would face up to a year in jail and a $53,000 fine.

“I tend to believe that a young Arab man from a poor suburb who posts a video of police brutality in his neighborhood will be more at risk of being found guilty than a journalist who did a video during a protest,” she said.

A dispute has broken out among French government officials over how to describe a wave of violent incidents this summer and how bad the situation is.

Amal Bentousi’s brother Amine was shot in the back and killed by a police officer in 2012. The officer was sentenced to a five-year suspended prison sentence. Along with other family members of police-shooting victims, she launched a mobile phone app in March called Emergency-Police Violence to record abuses and bring cases to court.

“Some police officers already have a sense of impunity.... The only solution now is to make videos,” she said. The app has been downloaded more than 50,000 times.

“If we want to improve public confidence in the police, it does not go through hiding the truth,” she added.

The proposed law is partly a response to demands from police unions, who say it will provide greater protection for officers.

Police fire tear gas and block demonstrators from marching through Paris and clash with far-right groups “guarding” monuments in London.

Abdoulaye Kante, a Black police officer with 20 years of experience in Paris and its suburbs, is both a supporter of the proposed law and strongly condemns police brutality and violence against officers.

“What people don’t understand is that some individuals are using videos to put the faces of our colleagues on social media so that they are identified, so that they are threatened, or to incite hatred,” Kante said.

“The law doesn’t ban journalists or citizens from filming police in action.... It bans these images from being used to harm, physically or psychologically,” he said. “The lives of officers are important.”

A “tiny fraction of the population feeds rage and hatred” against police, Jean-Michel Fauvergue, a former head of elite police forces and a lawmaker in Macron’s party who is a co-author of the bill, said in the National Assembly. “We need to find a solution.”

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Justice Minister Eric Dupond-Moretti has acknowledged that “the intent [to harm] is something that is difficult to define.” The government appears ready to back revamping part of the proposed law.

Activists consider the draft law one more step in a series of security measures passed by French lawmakers to extend police powers at the expense of civil liberties. A statement signed by more than 30 groups of families and friends of victims of police abuses said that, since 2005, “all security laws adopted have constantly expanded the legal field allowing police impunity.”

Riots in 2005 exposed France’s long-running problems between police and youths in public housing projects with large immigrant populations.

In recent years, numerous security laws have been passed following attacks by extremists.

French President Emmanuel Macron has vowed to stand firm against racism, but also stood up for police and for statues of colonial-era figures.

Critics noted a hardening of police tactics during protests or while arresting individuals. Hundreds of complaints have been filed against officers during the “yellow vest” protest movement against social injustice, which erupted in 2018 and saw weekends of violent clashes.

Interior Minister Gerald Darmanin said that out of 3 million police operations per year in France, some 9,500 end up on a government website that denounces abuses, which represents 0.3%.

France’s human rights ombudsman, Claire Hedon, is among the most prominent critics of the proposed law, which she said involves “significant risks of undermining fundamental rights.”

“Our democracy is hit when the population does not trust its police anymore,” she told the National Assembly.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.