A journalist. An army sergeant. An 80-year-old patient. Haitian human rights group details gang toll

SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico — A photographer slain in a drive-by shooting. An 80-year-old patient executed in a hospital surgery room. A couple decapitated as they closed their small store for the day.

A new report released by a Haitian human rights group details the horrific violence unleashed this year by gangs who kill, rape and maim with impunity amid a political vacuum.

“This year it’s much worse, and it’s all about the gangs,” Pierre Espérance, executive director of the National Human Rights Defense Network, said this week. “They have much more power, and they occupy more space.”

The group seeks to hold those responsible accountable, and it relies on people on the ground to collect victims’ names, ages and occupations to ensure they don’t remain anonymous amid a surge in slayings. The killings are difficult to track and are not reported by an underfunded and under-resourced police department overwhelmed by gangs.

More than 1,550 people have been killed across Haiti and more than 820 injured from January to March 22, according to the United Nations.

The report released Wednesday by the rights group found that among those killed were seven people aboard a sailboat traveling west of Port-au-Prince that was providing public transportation; nine bus passengers traveling on the main road that connects Port-au-Prince to the central Artibonite region; and a sergeant at the headquarters of Haiti’s armed forces who was struck in the head by a stray bullet.

Could Ukraine lose the war? Once nearly taboo, the question hovers in Kyiv, but Ukrainians believe they must fight for their lives against Putin’s troops.

Other victims include a 7-year-old boy, a woman who was director of a girls’ school, a 28-year-old basketball player, the chief accountant for the Secretariat of State Literacy and a 26-year-old sports reporter struck by a stray bullet while at home.

The report also detailed widespread armed attacks on multiple neighborhoods in which at least 67 people were killed as gangs set fire to homes, forcing survivors to flee. Some 17,000 people have been left homeless as a result, with many cramming into overcrowded, makeshift shelters.

Some of those fleeing sought refuge on the premises of the Institute of Social Welfare and Research in early March, but police pushed back the crowd in a scuffle that ended with the death of a 14-year-old boy, the report found.

Haiti struggles with poverty, a legacy of colonialism, and European and U.S. interference. But experts blame the latest violence in part on street gangs’ use by rulers.

Gang rapes also are common during attacks on neighborhoods, with at least 64 reported rape survivors from January to March. The number, however, is believed to be much higher given the stigma around sexual assaults.

Among those injured was a woman whose jaw was crushed by a stray bullet, the report found.

As gang violence continues unabated, medical workers have struggled to help the wounded and ill. Haiti’s biggest public hospital remains closed, along with at least a dozen other smaller hospitals and clinics.

Meanwhile, basic supplies such as fuel, oxygen and medications, including pain killers, are scarce given that Haiti’s main seaport remains largely shut down and its main international airport closed for more than a month.

“Consequently, patients must pay for everything,” the report stated.

In one hospital, pregnant women must provide a document proving they bought fuel in order to receive care, according to the report.

“The situation described in this document, aggravated by the violation of the right to the free circulation of goods and services, risks leading to an unprecedented humanitarian crisis if no measures are adopted immediately,” the report said.

Many of the killings took place after gangs launched large-scale attacks on Feb. 29, burning police stations, opening fire on the main airport and storming Haiti’s two biggest prisons, releasing more than 4,000 inmates. They also plundered several consulates and set fire to the home of Haiti’s National Police chief, the report found.

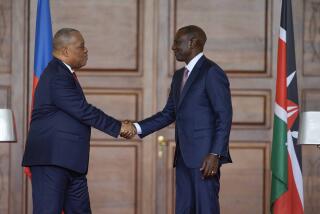

The attacks were meant to prevent the return of Prime Minister Ariel Henry to Haiti. He was in Kenya at the time to push for a U.N.-backed deployment of a police force from the East African country, and he remains locked out of Haiti.

Henry has pledged to resign once a transitional council responsible for appointing a new prime minister and Cabinet is created. But the National Human Rights Defense Network said it was concerned about the council since some of the members come from sectors that “do not inspire confidence, due to their past or present behavior.”

“It is the duty of the population to remain vigilant and monitor all the decisions and actions of the council in order to prevent the state’s coffers from being plundered and acts of corruption from being perpetrated,” the report stated.

The report also detailed at least 48 kidnappings for ransom. Among the victims: a judge, a priest, a mayor, a well-known doctor, a street vendor, six nuns and nearly a dozen bus passengers.

Espérance, with the human rights group, blamed what he called complicity between gangs and police and the country’s elite for the current situation, noting that Haiti’s National Police are overwhelmed.

“They’re unable to function,” he said in a phone interview. “The gangs are much more comfortable.”

On Thursday, activists and U.S. lawmakers held a news conference warning about Haiti’s situation as they called for a halt to deportations of Haitian nationals living in the United States, among other things.

“Anything less is a death sentence,” said Democratic Rep. Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts.

Coto writes for the Associated Press.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.