Coronavirus sparks exodus of foreign-born people from U.K.

- Share via

LONDON — The coronavirus has sparked an exodus of immigrants from the U.K. in what is likely to be the largest fall in Britain’s population since World War II, according to a statistical analysis of official data.

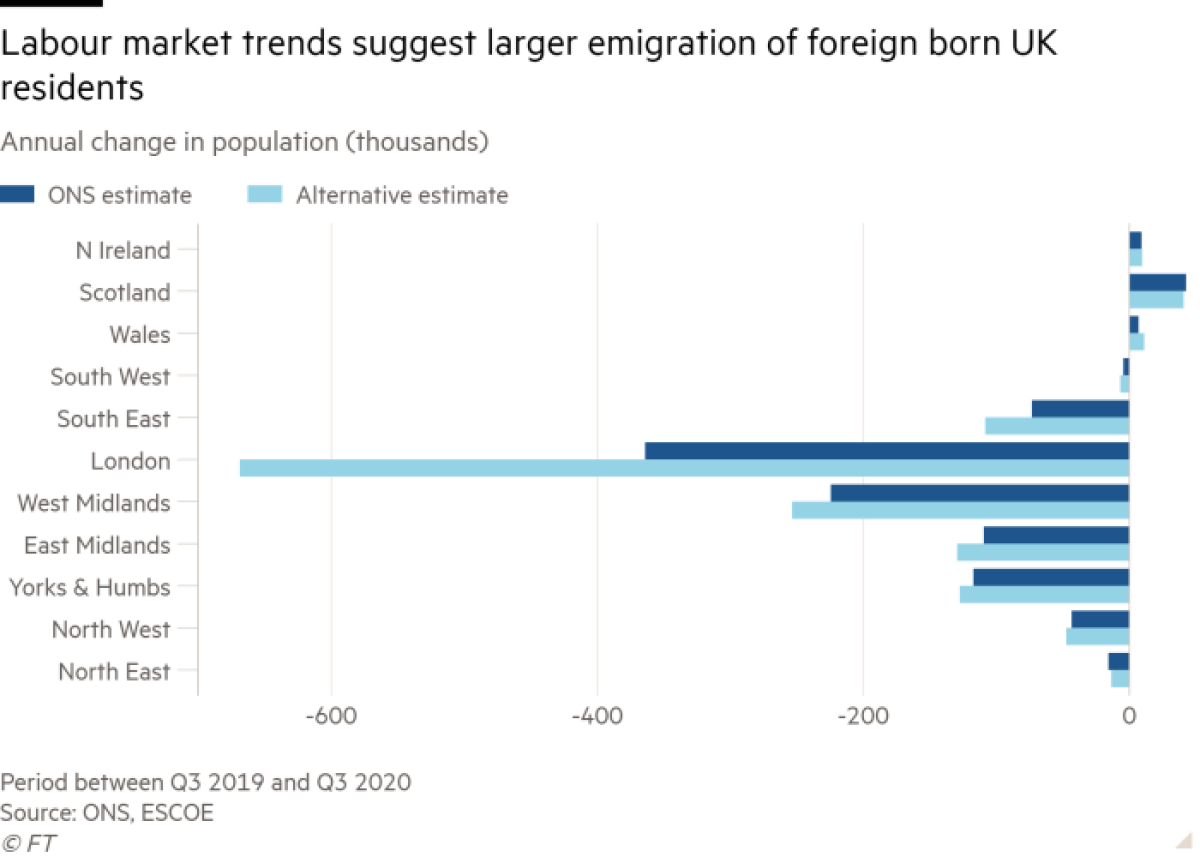

A blog, published on Thursday by the government-funded Economic Statistics Center of Excellence, estimated that up to 1.3 million people born abroad left the U.K. between the third quarter of 2019 and the same period in 2020.

In London alone, almost 700,000 foreign-born residents have probably moved out, the authors of the blog calculated, leading to a potential 8% drop in the capital’s population last year.

The study drew a clear link between the departure of so many foreign-born nationals and the high number of job losses in hard-hit sectors such as hospitality, which has typically relied on overseas workers.

“It seems that much of the burden of job losses during the pandemic has fallen on non-U.K. workers and that has manifested itself in return migration, rather than unemployment,” the authors concluded.

Large changes in regional populations would make it difficult for the National Health Service to distribute COVID-19 vaccines fairly around Britain and may raise questions over how business will fill jobs traditionally taken by European migrants.

The picture is further complicated by post-Brexit immigration rules. These mean that European Union nationals who left the U.K. in the past year will need work visas to return and work in Britain. Those with settled status would be able to return to fill jobs, but new migrants would not.

The statistics center’s calculations assume that official data, published by the Office for National Statistics, are flawed. The blog highlighted “hardly plausible” official statistics that showed employment of British-born people in London rising during the pandemic.

With officials unable to collect data in the usual way at airports and other transport hubs owing to the pandemic, the Office of National Statistics has faced severe difficulties in measuring migration numbers.

However, the agency has continued to measure employment trends during the pandemic through its labor force survey and has used this to form the basis of its regional population analysis.

Having found far fewer migrants to survey, especially in London, the national agency gave all the Londoners it surveyed much higher weights. This has resulted in the official figures showing the number of British-born employed Londoners rising sharply.

The blog by the statistics center noted that the official figures show that the number of employed people in London and born in the U.K. grew by more than 250,000 in the year leading to the third quarter of 2020, with the total British-born population in the capital rising by 440,000.

And yet the capital has been hit hardest by COVID-19 and has a high concentration of jobs in tourism, entertainment and hospitality, which have disappeared over the last year. The agency figures showing an increase of British workers in London jobs did not remotely match other data such as benefit claimants in the capital or customs data from income tax records.

The authors of the study, Michael O’Connor and Jonathan Portes, said the only way to reconcile hard evidence of an employment crash in London with official figures suggesting a surge of U.K.-born employees was big problems in the agency’s migration assumptions.

The agency does not dispute the logic of the analysis and accepts anomalies being in its current estimates of employment and population. It blames these on difficulties of counting migration during the pandemic when its normal surveys have been suspended.

The agency added that it was working to transform its migration statistics and has promised an update early this year on its progress in improving them.

© The Financial Times Ltd. 2021. All rights reserved. FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.