1 in 5 Americans has lost someone close in the pandemic, poll finds

- Share via

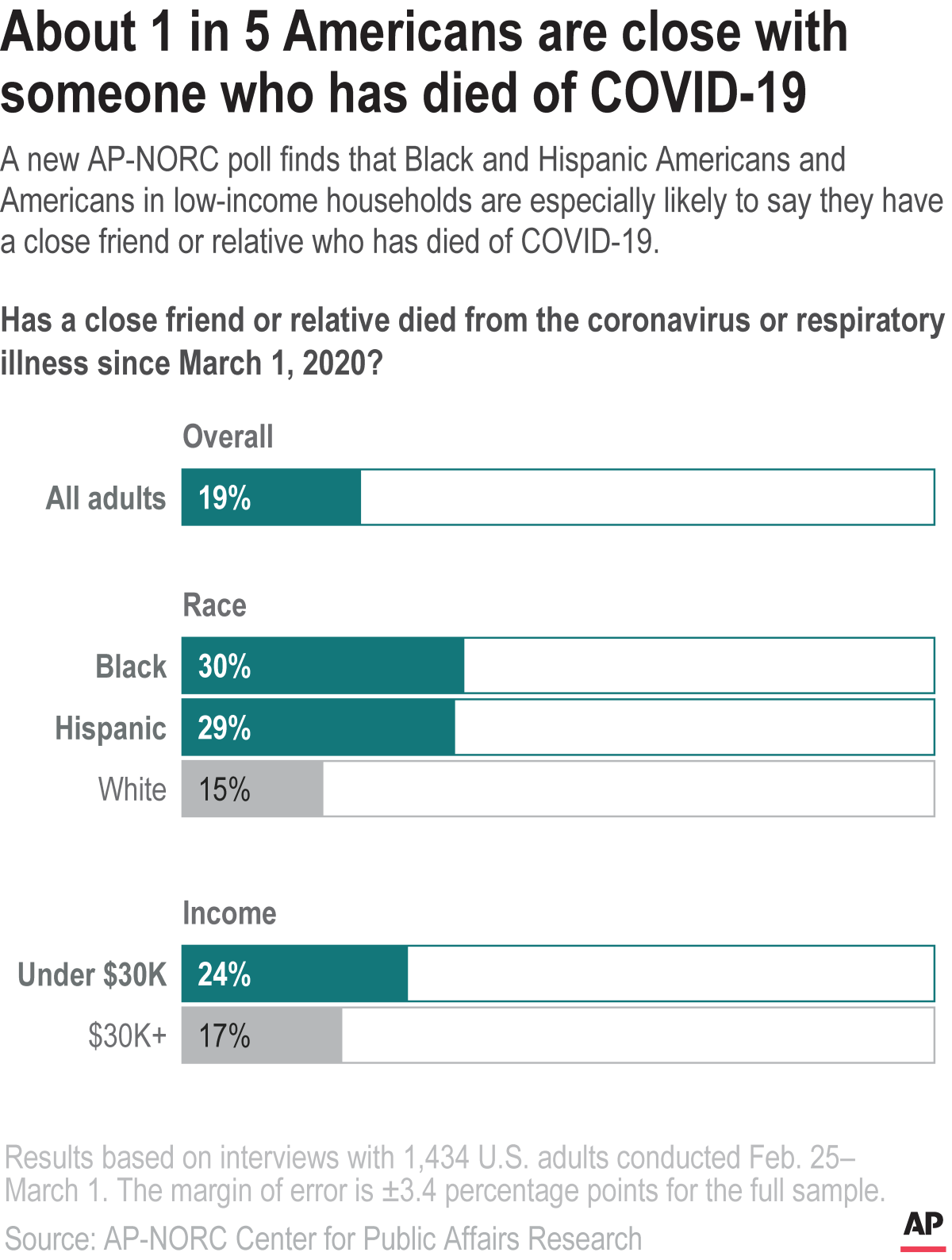

WASHINGTON — About 1 in 5 Americans say they have lost a relative or close friend to COVID-19, highlighting the division between heartache and hope as the country itches to get back to normal a year into the COVID-19 pandemic.

A new poll from the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research illustrates how the stage is set for a two-tiered recovery.

The public’s worry about the virus has dropped to its lowest point since the fall, before the holidays brought skyrocketing cases into the new year.

But people still in mourning express frustration at the continued struggle to stay safe.

“We didn’t have a chance to grieve. It’s almost like it happened yesterday for us. It’s still fresh,” said Nettie Parks of Volusia County, Fla., whose only brother died of COVID-19 last April. Because of travel restrictions, Parks and her five sisters have yet to hold a memorial.

Parks, 60, said she retired from her customer service job last year in part because of worry about workplace exposure. She now watches with dread as more states and cities relax health rules.

Only about 3 in 10 Americans are very worried about themselves or a family member becoming infected with the virus, down from about 4 in 10 in recent months. Still, a majority are at least somewhat worried.

“They’re letting their guard down, and they shouldn’t,” Parks said. “People are going to have to realize this thing is not going anywhere. It’s not over.”

A widespread study of nearly 200,000 U.S. adults hospitalized with COVID-19 found that the oldest patients were 19 times more likely to die than the youngest patients.

COVID-19’s toll is staggering, with more than 527,000 dead in the U.S. alone, and counting.

But “it’s hard to conceptualize the true danger if you don’t know it personally,” said Dr. K. Luan Phan, chief of psychiatry at Ohio State University’s Wexner Medical Center.

For those who lost a loved one, “that fear is most salient in them. They’re going to be a lot more cautious as businesses reopen and as schools start back,” Phan said.

And without that firsthand experience, even people who have heeded health officials’ pleas to stay masked and keep their distance are succumbing to pandemic fatigue because “fears tend to habituate,” he said.

Communities of color were hardest hit by the coronavirus. The AP-NORC poll found about 30% of Black Americans, like Parks, and Latinos knew a relative or close friend who had died from the virus, compared with 15% of white people.

That translates into differences in how worried people are about a virus that will remain a serious threat until most of the country — and the world — is vaccinated.

Despite recent drops in cases, 43% of Black Americans and 39% of Latino Americans are very or extremely worried about themselves or a loved one becoming ill with COVID-19, compared with just 25% of white people. (For other racial and ethnic groups, sample sizes are too small to analyze.)

Although vaccines offer real hope for ending the scourge, the poll also found about 1 in 3 Americans didn’t intend to get their shot. The most reluctant: younger adults, people without college degrees, and Republicans.

The hardest-hit are also having the hardest time getting vaccinated: 16% of Black Americans and 15% of Latinos say they already have received at least one shot, compared with 26% of white people. But majorities in each group want to be vaccinated.

Americans are warming up to COVID-19 vaccines, with 19% saying they’ve already received at least one dose and 49% intending to do so when they get the chance.

Demand for vaccines still outstrips supply, and about 4 in 10 Americans, especially older adults, say the sign-up process has been poor.

John Perez, a retired teacher and school administrator in Los Angeles, spent hours trying to sign up online before giving up. Then a friend found a drive-through vaccination site with openings.

“When I was driving there for the first shot, I was going through a tunnel of emotions,” the 68-year-old said. “I knew what a special moment it was.”

Overall, confidence in the vaccines has strengthened slowly. The poll found 25% of Americans weren’t confident the shots were properly tested. That figure was down somewhat from the 32% who said in December, before the first vaccines were approved, that they believed the shots weren’t being tested properly.

“We were a little skeptical when it was first coming out because it was so politicized,” said Bob Richard, 50, of Smithfield, R.I. But now he says his family is inclined to get the shots — if they can sort through the appointment system when it’s their turn.

The poll found two-thirds of Americans said their fellow citizens nationwide hadn’t taken the pandemic seriously enough.

“The conflict with people who don’t take it serious as I do, it’s disappointing,” said Wayne Denley, 73, of Alexandria, La.

Early on, he and his wife started keeping a list of people they knew who’d gotten sick. By November, they’d counted nine deaths and dozens of infections. He’d share the sobering list with people doubtful of the pandemic’s toll, yet he’d still see unmasked acquaintances while running errands.

“I’m glad I wrote them down — it helped make it real for me,” Denley said. “You sort of become numb to it.”

A pair of studies in Science examine how coronavirus variants evolve in human hosts and why experts are concerned about relaxing restrictions too soon.

There are exceptionally wide partisan differences. Sixty percent of Democrats said their local communities failed to take the threat seriously enough, and even more, 83%, said the country as a whole didn’t either.

Among Republicans, 31% said their localities didn’t take the pandemic seriously enough, and 44% said that of the country. But another third of Republicans said the U.S. overreacted.

The differences translate into behavior: More than three-quarters of Democrats say they always wear a mask around others, compared with about half of Republicans.

And the divisions have Phan, the psychiatrist, worried.

“We’ve survived something that we should be grateful for having survived. How do we repay or reciprocate that good fortune? The only way to do it is to be stronger in the year after the epidemic than before,” he said.

The AP-NORC poll of 1,434 adults was conducted between Feb. 25 and March 1 using a sample drawn from NORC’s probability-based AmeriSpeak Panel, which is designed to be representative of the U.S. population. The margin of sampling error for all respondents is plus or minus 3.4 percentage points.