He switched subway cars to be closer to the exit. It probably saved his life

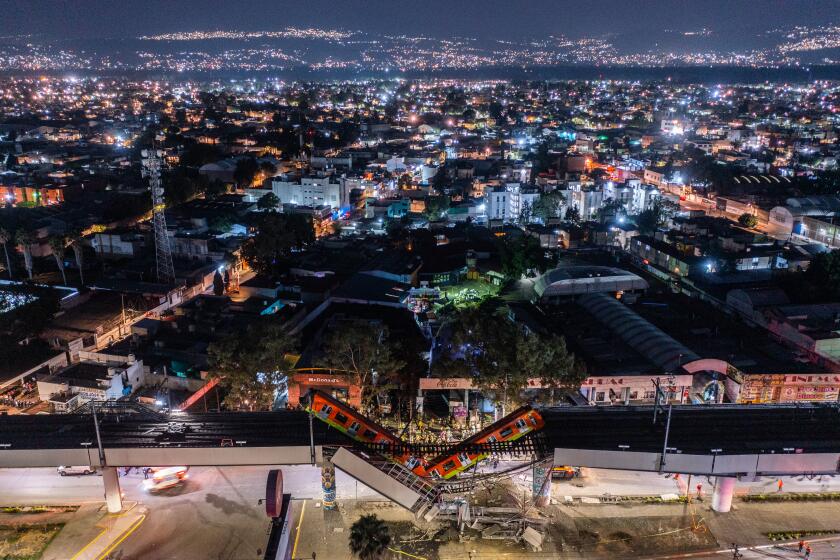

MEXICO CITY — A decision to change cars to be closer to a station exit may have saved Erik Bravo, who survived the collapse of an elevated subway line in Mexico City that killed 25 people and injured about 80 others.

Bravo, a 34-year-old financial advisor, said Thursday that he and two colleagues from work were accustomed to taking the Mexico City Metro’s Line 12 home from their jobs. His two friends got off as usual late Monday at their respective stops.

Alone, Bravo decided to put on his headphones and use the time before his stop at the Olivos station to walk forward through a couple of the train’s subway cars to be closer to the station’s exit, at the end of the platform, when he arrived.

The move probably spared him from disaster.

“You realize that, in some way, you got a second chance, because that could have been you,” Bravo said.

As his car began pulling in to the station, he felt the train jerk, as if pulled from behind, and shudder to a stop as smoke filled the cabin. A male passenger shouted for people to lie on the floor for safety.

Anger and frustration add to the grief of the families of those who died when a Mexico City Metro train plunged from a collapsed overpass.

“People were desperate, they tried to break the glass, they wanted to open the windows to escape,” Bravo recalled.

The automatic doors wouldn’t open, but a police officer told them that a door was open farther back.

Bravo walked in that direction not knowing that the last two cars of the subway train had fallen into the rubble of the elevated rail bed, which had collapsed and plunged onto the roadway below.

In one of the last cars still standing on the track, two people lay unconscious on the floor. A little girl was crying. “I saw a man with his two little girls,” Bravo said, but he doesn’t know what happened to them.

At least 23 people died in an overpass collapse on the Mexico City Metro, which is among the busiest in the world.

Stunned, he walked home.

“When I got home ... we began to look at everything that was coming out on the internet,” Bravo said. “It was a shock — I had been there. We began to see that people had died, people were missing, wounded, and here I was, unhurt, still here.”

Authorities say the collapse occurred after a steel beam that held up the elevated line broke. Investigators are trying to figure out how and why.

The line, the subway’s newest, stretches far into the city’s south side. Like many of the Metro system’s dozen subway lines, it runs underground through more central areas of Mexico City but surfaces onto elevated concrete structures on the outskirts.

An overpass of the Mexico City Metro collapsed, sending a train crashing onto the road below, trapping cars and killing at least 24 people.

Allegations of poor design and construction on Line 12 emerged soon after it was inaugurated in 2012, and the line had to be partly closed in 2014 so tracks could be repaired.

The city’s magnitude-7.1 earthquake in 2017 revealed some structural defects that experts say should have resulted in a total closure and complete inspection of the line. Instead, authorities applied some patchwork fixes and reopened it.

María Isabel Fuentes, a domestic worker, said the subway’s defects had long worried her. “Ever since it opened, it was scary,” she said.

Added Bravo: “Yes, you knew there were defects, but not that kind of defect that would cause what happened to occur.”

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Many think the tragedy was preventable.

“They could have avoided this if the government had paid attention to the services they provide us,” said another regular passenger on the line, Ana María Luna. “But they didn’t pay attention to all the reports” of defects, she said.

Even with the subway, Luna had to travel for hours to get to her job as a security guard. Since the disaster, her commute has stretched to three hours.

The collapse has temporarily closed the subway line, leaving thousands of residents on the south side dependent on bus service.

Bravo has kept busy since his near-miss with disaster, fixing up an old motorcycle he owns so he can get to work now that the line is out of service. His nights have been sleepless, though, as he reflects on what might have been.

“In some way, I feel thankful, grateful to someone, something up there that for some reason decided it wasn’t my time,” Bravo said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.