Secrecy shrouds Afghan refugees sent by U.S. to base in Kosovo

WASHINGTON — The U.S. is welcoming tens of thousands of Afghans airlifted out of Kabul but has disclosed little publicly about a small group that remains overseas: dozens who triggered potential security issues during vetting and have been sent to an American base in the Balkan nation of Kosovo.

Human rights advocates have raised concerns about the Afghans diverted to Camp Bondsteel in Kosovo over the past six weeks, citing a lack of transparency about their status and the reasons for holding them back. It’s unclear what might become of any who cannot be cleared to come to the United States.

“We are obviously concerned,” said Jelena Sesar, a researcher for Amnesty International who specializes in the Balkans. “What really happens with these people, especially the people who don’t pass security vetting? Are they going to be detained? Are they going to have any access to legal assistance? And what is the plan for them? Is there any risk of them ultimately being returned to Afghanistan?”

The Biden administration says it’s too soon to answer some of these questions, at least publicly, as it works feverishly to resettle the Afghans who were evacuated following the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August.

The lack of public information has made it a challenge for those who closely track the fate of refugees. “There’s not a lot of transparency in terms of how the security check regime works,” said Sunil Varghese, policy director for the International Refugee Assistance Project. “We don’t know why people are being sent to Kosovo for additional screening, what that additional screening is, how long it will take.”

The plan was blocked by the White House Vaccine Task Force, exasperating San Diego healthcare providers.

So far, more than 66,000 Afghans have arrived in the U.S. since Aug. 17, undergoing what the government portrays as a rigorous vetting process to screen out national security threats from among a population that includes people who worked as interpreters for the American military as well as their own country’s armed forces.

Of those, about 55,000 are at U.S. military bases around the country, where they complete immigration processing and medical evaluations and quarantine before settling in to the United States. There are still 5,000 people from the evacuation at transit points in the Middle East and Europe, according to the Department of Homeland Security, which is managing the effort known as Operation Allies Welcome.

The resettlement effort is under intense scrutiny following waves of criticism of President Biden for the frantic evacuation of U.S. forces and allies as part of the withdrawal from Afghanistan, which was put in motion when former President Trump’s administration signed a peace deal with the Taliban to end America’s longest war.

Trump and other Republicans say the Biden administration has allowed Afghan refugees into the U.S. without sufficient background checks. Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas has defended the screening and said there have been only minimal threats detected among the arriving refugees.

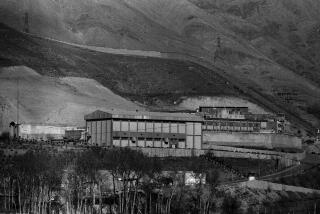

The exact number at Camp Bondsteel in Kosovo, a small nation in southeastern Europe that gained independence from Serbia with U.S. support in 2008, fluctuates as new people arrive and others leave when security issues, such as missing documents, are resolved, according to U.S. officials.

The government of Kosovo, a close U.S. ally, has agreed to let the refugees stay in its territory for a year. The country also hosts a separate group at site adjacent to Bondsteel known as Camp Bechtel, where Afghans who worked for NATO nations during the war are staying temporarily until they are resettled in Europe.

For several weeks, there were about 30 Afghan evacuees, along with approximately 170 family members, at Camp Bondsteel because of red flags, according to one U.S. official who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss information not publicly released.

They are in a kind of limbo because they aren’t detained, but they aren’t necessarily free to leave either at this point.

They volunteered to be evacuated from Afghanistan but were flagged at one of the transit points in Europe or the Middle East and told they had to go to Kosovo. Some chose to bring their families with them while authorities work with analysts and other experts from the FBI, DHS and other agencies to resolve questions about their identity or past associations, said a senior administration official.

They are free to move about the base but can’t leave under conditions set by the government of Kosovo, said the senior official, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss security and diplomatic issues.

Those sent to Bondsteel are people who require “significant further consideration,” involving analysis and interviews, before authorities feel comfortable allowing them to move on to the U.S., the senior administration official said.

In some cases, the analysis has led to a determination that they are “suitable for onward travel to the United States,” while for others the “work remains ongoing” and their cases remain unresolved, said the senior administration official, without giving a precise breakdown on the numbers involved.

The U.S. has not sent anyone back to Afghanistan and will decide the fate of anyone who can’t make it through the vetting process on an “individualized” basis, which in some cases might mean resettling them in another country, this official said.

In the meantime, though, Bondsteel remains off-limits to outsiders, including lawyers who might potentially represent people there if they aren’t ultimately allowed to enter the U.S., a situation that doesn’t sit right with advocates like Sesar. “There is not real access to the camp,” she said. “There’s no public or independent scrutiny of what happens in there.”

Associated Press writer Lolita C. Baldor contributed to this report,

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.