Interior secretary seeks to rid U.S. of derogatory place names

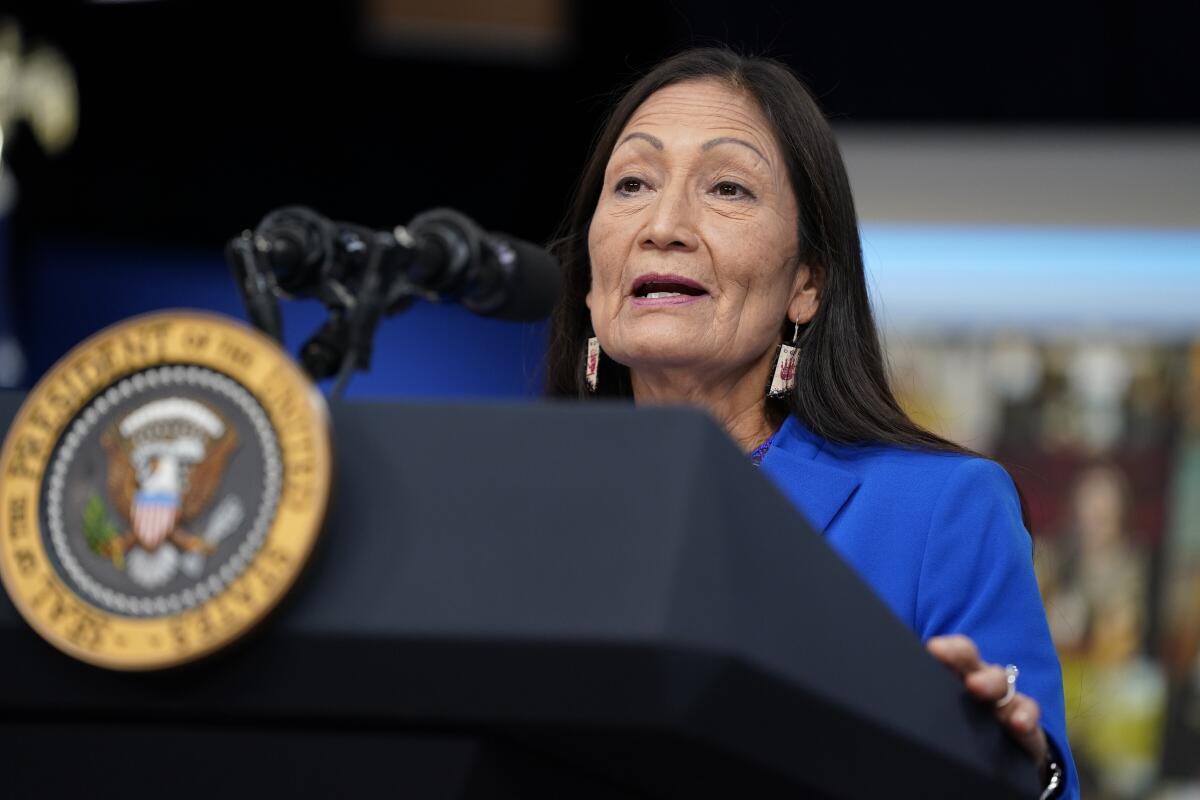

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland on Friday formally declared “squaw” a derogatory term and said she is taking steps to remove it from federal government use and to replace other derogatory place names.

Haaland is ordering a federal panel tasked with naming geographic places to implement procedures to eliminate what she called racist terms from federal use. The decision provides momentum to a movement that has included the dismantling of other historical markers and monuments considered offensive across the country.

“Our nation’s lands and waters should be places to celebrate the outdoors and our shared cultural heritage — not to perpetuate the legacies of oppression,” Haaland said in a statement. “Today’s actions will accelerate an important process to reconcile derogatory place names and mark a significant step in honoring the ancestors who have stewarded our lands since time immemorial.”

The first Native American to lead a Cabinet agency, Haaland is from Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico.

The U.S. Senate on Thursday confirmed Oregon resident and tribal citizen Charles F. “Chuck” Sams III as head of the National Park Service, making him the first Native American to hold the position.

Haaland said previously that Sams, a citizen of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, would be an asset as the administration works to make national parks more accessible to everyone.

The Native American Rights Fund applauded Haaland’s move to address derogatory place names, saying action by the federal government is long overdue.

“Names that still use derogatory terms are an embarrassing legacy of this country’s colonialist and racist past,” said John Echohawk, the group’s executive director. “It is well past time for us, as a nation, to move forward, beyond these derogatory terms, and show Native people — and all people — equal respect.”

Environmentalists also praised the action, saying it marked a step toward reconciliation.

Under Haaland’s order, a federal task force will find replacement names for geographic features on federal lands bearing the term “squaw,” which has been used as a slur, particularly for Indigenous women. A database maintained by the Board on Geographic Names shows there are more than 650 federal sites with names that contain the term.

The task force will be made up of representatives from federal land management agencies and experts with the Interior Department. Tribal consultation and public feedback will be part of the process.

The process for changing U.S. place names can take years, and federal officials said there are currently hundreds of proposed name changes pending before the board.

Haaland also called for the creation of an advisory committee to solicit, review and recommend changes to other derogatory geographic and federal place names. That panel will be made up of tribal representatives and civil rights, anthropology and history experts.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Board on Geographic Names took action to eliminate the use of derogatory terms for Black and Japanese people.

The board also voted in 2008 to change the name of a prominent Phoenix mountain from Squaw Peak to Piestewa Peak to honor Army Spc. Lori Piestewa, the first Native American woman to die in combat while serving in the U.S. military.

In California, the Squaw Valley Ski Resort changed its name to Palisades Tahoe earlier this year. The resort is in Olympic Valley, which was known as Squaw Valley until it hosted the 1960 Winter Olympics. Tribes in the region had been asking the resort for a name change for decades.

Colorado’s advisory naming panel also has recommended renaming Squaw Mountain near Denver in honor of a Native American woman who acted as a translator for tribes and white settlers in the 19th century. Northern Cheyenne tribal members also filed an application with the federal naming board in October to change the mountain’s name.

There is also legislation pending in Congress to address derogatory names on geographic features on public lands. States from Oregon to Maine have passed laws prohibiting the use of the word “squaw” in place names.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.