Satellite photo suggests Russian coal mine spewed 99 tons of methane in an hour

BERLIN — A private company that uses satellites to spot sources of methane emissions around the globe said Wednesday that it detected one of the largest artificial releases of the potent greenhouse gas ever seen, coming from a coal mine in Russia earlier this year.

Montreal-based GHGSat said one of its satellites, known as Hugo, observed 13 methane plumes at the Raspadskaya mine in Siberia on Jan. 14. The incident likely resulted in about 99 tons of methane being belched into the atmosphere in the space of an hour, the company calculated.

“This was a really, really dramatic emission,” Brody Wight, GHGSat’s director of energy, landfills and mines, told the Associated Press.

Cutting down methane emissions caused by fossil-fuel facilities has become a priority for governments seeking quick, effective steps against climate change. That’s because methane is a powerful heat-trapping gas second only to carbon dioxide, which stays in the atmosphere for longer.

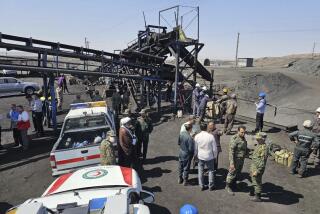

GHGSat said the plumes detected at Raspadskaya may have been released intentionally as a safety measure since the gas can seep out of mines and ignite with potentially deadly outcomes. Two methane explosions and a fire killed 91 people at the mine in 2010, one of the worst such disasters in post-Soviet times.

Companies can prevent the uncontrolled release of methane through best practices. Captured gas can be burned as fuel, lessening its global-warming impact.

The International Energy Agency says methane emissions are 70% higher than the official figure provided by governments worldwide.

GHGSat said it measured further plumes over the mine during subsequent flyovers the following weeks, though these didn’t reach the same “ultra emission” scale seen Jan. 14.

“Even if it’s only for a short period of time, it doesn’t take long for this to be a significant emission,” said Wight.

Manfredi Caltagirone, who heads the International Methane Emissions Observatory at the United Nations Environment Program, said he was not aware of any bigger release of methane from a coal mine.

“If this event is the result of an accumulation of methane that has been then released all at once instead of over several days, the environmental impact would be the same as if a smaller plume was to be released constantly over several days,” said Caltagirone, who wasn’t involved in the GHGSat observation.

President Biden joined more than 100 other countries in pledging to cut methane emissions, a climate goal we can achieve fast.

“But from a safety perspective, it is worrisome,” he said, citing recent mine explosions in Poland that killed 13 people.

Still, the release was likely a very rare event because other methane-measuring satellites would have picked them up otherwise, said Caltagirone.

GHGSat said it alerted the Raspadskaya mine operator to its findings but received no response. The operator also didn’t respond to a request for comment from the AP.

Several private and government satellites have been launched into orbit in recent years to help pinpoint methane leaks and raise awareness of the risks they pose to the climate and people’s health.

In one of the most publicized methane leaks in the U.S., a 2015 blowout at a natural gas storage well in California sickened residents of the San Fernando Valley and led to the evacuation of 8,000 homes.

More to Read

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.