The 53 migrants who died in Texas included this college-educated Honduran couple

MEXICO CITY — Alejandro Miguel Andino Caballero had almost completed his university studies in marketing. His fiancee, Margie Támara Paz Grajeda, had earned a degree in economics. Both viewed education as a means to launch careers and surmount humble origins in Honduras, where endemic poverty, crime and corruption have long choked off avenues of social advancement.

But few doors opened for the ambitious young couple. The pandemic and two major hurricanes in recent years only dampened economic prospects in one of the hemisphere’s poorest nations.

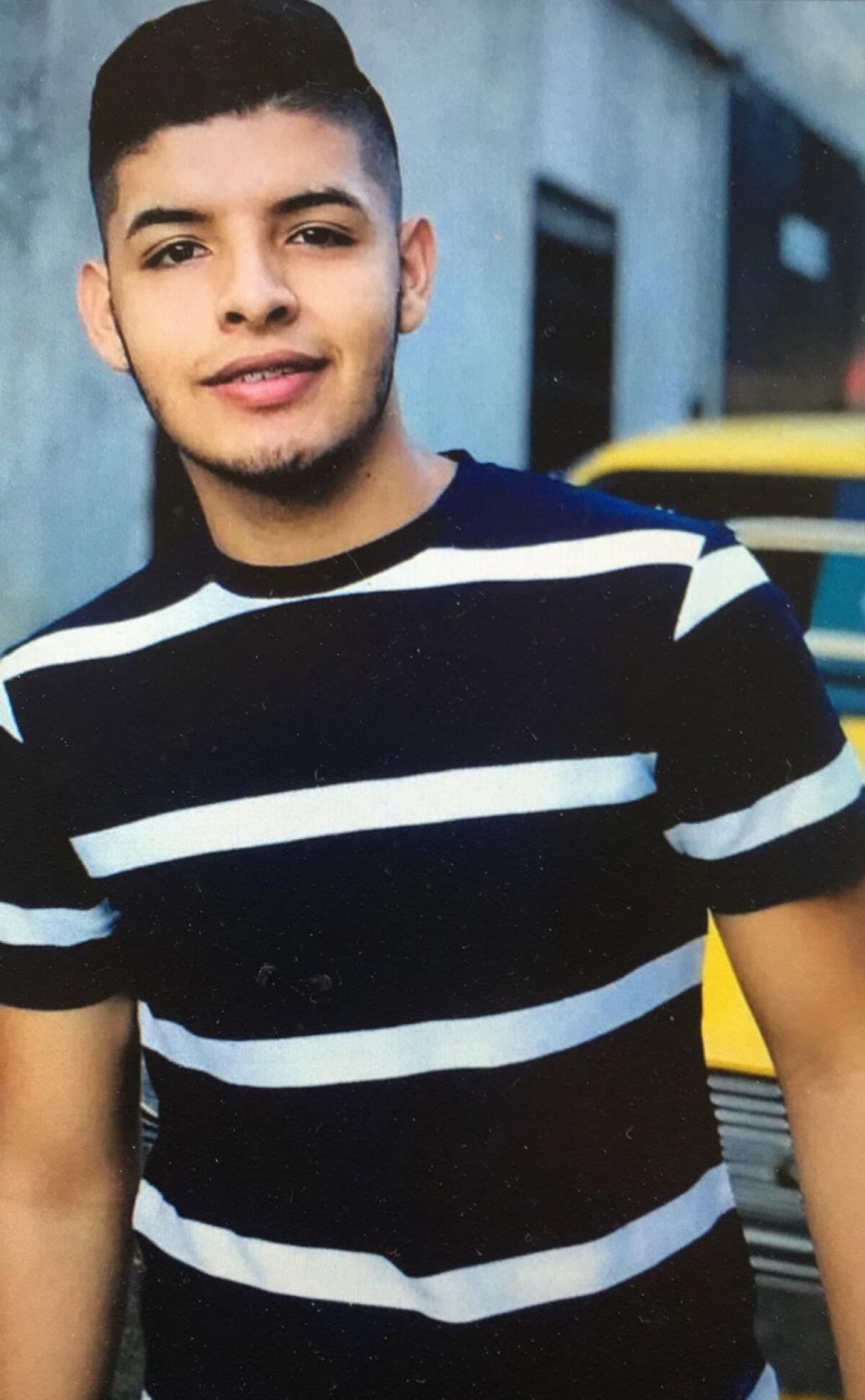

So like many of their compatriots, Caballero, 23, and Paz Grajeda, 24, set out for the United States. Joining them was Caballero’s 18-year-old brother, who had also lost hope for his future in Honduras.

“They didn’t leave because they wanted to abandon their lives in Honduras, or because they didn’t like their country, or because they wanted to forsake their families,” the siblings’ mother, Karen Caballero, said Friday by telephone from her home in Las Vegas, Honduras. “They left because they had no opportunity here to advance.”

The three were among the 53 people — most, if not all, from Central America and Mexico — who perished after being smuggled in a sweltering tractor-trailer discovered Monday on the outskirts of San Antonio. It was one of the deadliest human-trafficking tragedies in U.S. history.

As authorities continue to identify the victims and notify next of kin, officials have slowly been releasing the names of those who died in the big rig — dubbed the “trailer of death” in the Latin American press. Their stories have resonated deeply in a region where emigration, despite its hazards, has long been the surest path to upward mobility in many communities.

Those who leave are strivers, seekers of opportunity, keen to improve their lot and help relatives back home in a time-honored tradition. Some aboard the tractor-trailer were from rural zones and had little opportunity to consider professional callings. Two of the dead were 13-year-old cousins from an Indigenous community in northern Guatemala.

The case of the Caballero brothers and Paz Grajeda is distinct. They don’t fit into the narrow stereotype of smuggled migrants.

Despite economic hardships, Caballero and his fiancee sought to remain in their homeland, studying and hoping to secure decent-paying jobs. At a time when U.S. policy is focused on creating employment in Central America to deter emigration, their story dramatizes how even many talented young people aspiring to careers at home have been thwarted.

“They had their dreams, their goals,” said Karen Caballero, still in shock from the loss of two sons and a woman she viewed as her likely future daughter-in-law.

Caballero and Paz Grajeda met in high school and had been together ever since, his mother said. Both attended university in the city of San Pedro Sula, 60 miles north of Las Vegas.

But Paz Grajeda’s degree only netted her a low-paying job in a call center. Caballero also had trouble finding work and helped out at the family eatery in Las Vegas, an agricultural and mining town of 26,000 people.

In the Latin American press, photographs from social media accounts circulated showing Paz Grajeda navigating a kayak, she and Caballero embracing, and the couple and Caballero’s younger brother, Fernando José Redondo Caballero, loaded up with luggage and smiling for the camera, although it was unclear when and where the images were taken.

It was Fernando José, a teenage aficionado of soccer and poetry, who was initially keen about going to the United States. Unlike his older sibling, he had dropped out of school and showed little interest in academics.

“Imagine, Mom, if there is no work here for those who study, what is left for someone like me who didn’t study?” Fernando told his mother, BBC Mundo reported.

His older brother and fiancee eventually signed on. They began planning for the trip more than six months ago. “This wasn’t something we took lightly,” said Karen Caballero, 42, who has a daughter, 22, and an infant grandson still in Honduras.

Paz Grajeda had another motivation: She needed money to help her mother pay for cancer treatment.

“That’s why she made this trip, for my health,” her mother, Gloria Paz, told Honduras’ La Prensa newspaper. “I preferred that she stayed working where she was, in the call center. But she left and said: ‘No, mother, I am going to look for a good job to pay for your operation.’ ”

Relatives in Honduras and the U.S. chipped in to finance the trip, said Karen Caballero, who has a brother living in the United States. The initial planned destination was Houston.

The three left on June 4. Karen Caballero accompanied them as far as Guatemala. She wanted to be there to say goodbye.

“In my mind was the thought that years could pass before I saw them again,” she told La Prensa. “Because when one goes to the United States it’s difficult to return. I knew that five, 10, 15 years could pass before we were reunited again.”

In those final moments together, Caballero said she reassured Alejandro, who was nervous about the trip.

“Nothing will happen,” she said she told him. “You are not the first nor will you be the last human being to travel to the United States.”

She bid them farewell: “I gave them my blessing and said, ‘Children, do well on el otro lado [the other side] because here you couldn’t.’ ”

She stayed in touch via WhatsApp as the three made their way north through Mexico. She last heard from them last Saturday after they had crossed into Texas.

They were awaiting transport north.

McDonnell is a Times staff writer. Sanchez is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.