Oregon chief justice fires panel due to lack of public defenders

SALEM, Ore. — Oregon’s chief justice fired all the members of the Public Defense Services Commission on Monday, frustrated that hundreds of defendants charged with crimes and who cannot afford an attorney have been unable to obtain public defenders to represent them.

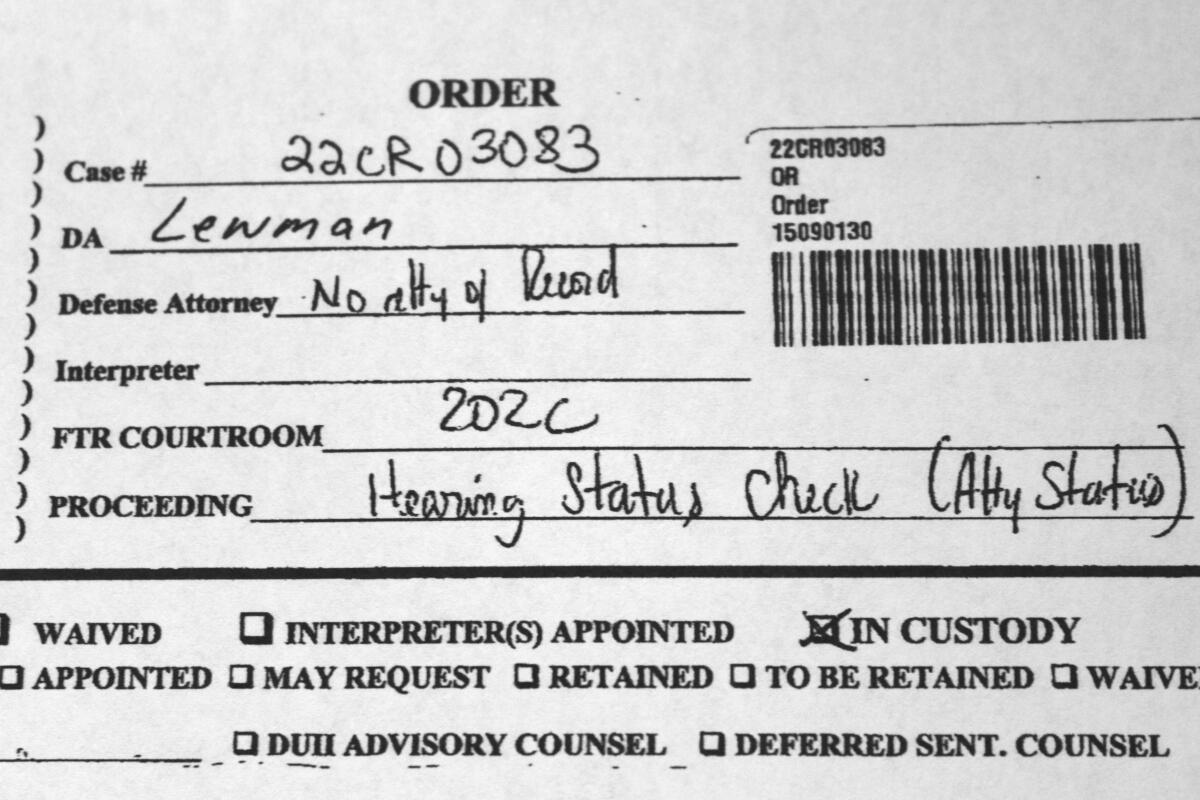

The unprecedented action comes as Oregon’s unique public defender system has come under such strain that it is at the breaking point. Criminal defendants in Oregon who have gone without legal representation due to a shortage of public defenders filed a lawsuit in May that alleges the state is violating their constitutional right to legal counsel and a speedy trial.

In a letter to the commission members, Chief Justice Martha Walters pointed out that their duty is to “ensure that Oregon provides public defense services consistent with the Oregon Constitution, the United States Constitution, and Oregon and national standards of justice.”

“Unfortunately, it is now clear that it is time to reconstitute the current commission,” she said.

Oregon’s public defender system is the only one in the nation that relies entirely on contractors: large nonprofit defense firms, smaller cooperating groups of private defense attorneys that contract for cases and independent attorneys who can take cases at will.

But some firms and private attorneys are periodically refusing to take new cases because of the workload. Poor pay rates and late payments from the state are also a disincentive. The American Bar Assn. found that Oregon has only 31% of the public defenders it needs.

Walters said that “systemic change” is called for and that the commission must collaborate with Oregon’s executive and legislative branches and the public defense community “to create a better system for public defense providers.”

The Public Defense Services Commission currently has nine members, in addition to Walters, who, as chief justice, serves as ex-officio permanent member. Walters made the dismissals effective on Tuesday and said that if any members want to serve on a reconstituted commission, they should apply by noon Tuesday.

One of the members is Steven Wax, who has deep experience in public defense. He was the U.S. public defender for the Oregon district for 31 years and is legal director of the Oregon Innocence Project, which focuses on wrongful convictions.

In a telephone interview, Wax said he is unhappy about the chief justice’s action.

“The commission has been working tirelessly on difficult issues and reforms,” Wax said. “Disagreement is inevitable. I was sorely disappointed to receive the chief justice’s letter.”

He declined to comment further, including whether he would apply to a reconstituted commission, an independent body that governs the Office of Public Defense Services and appoints its executive director. It’s primary mission is to establish “a public defense system that ensures the provision of public defense services in the most cost efficient manner.”

The chief justice appoints it members and can remove them, according to Oregon law.

“I never anticipated exercising this authority, but this issue is too important, and the need for change is too urgent, to delay,” Walters said.

Todd Sprague, spokesman for the Oregon Judicial Department, said that to his knowledge, the entire commission has never been dismissed before.

Oregon’s backlog has led to the dismissal of dozens of cases and, as of May, left an estimated 500 defendants statewide lacking legal representation.

Jesse Merrithew, an attorney representing plaintiffs in the lawsuit, said being deprived of a lawyer right after an arrest causes problems that are almost impossible to overcome later on, for example in obtaining surveillance video before it is erased that could back up a defendant’s case.

Oregon’s system was underfunded and understaffed before the COVID-19 pandemic, but the backlog grew amid a slowdown in court activity because of safety protocols.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.