Panel OKs name change of Colorado mountain tied to massacre of Native Americans

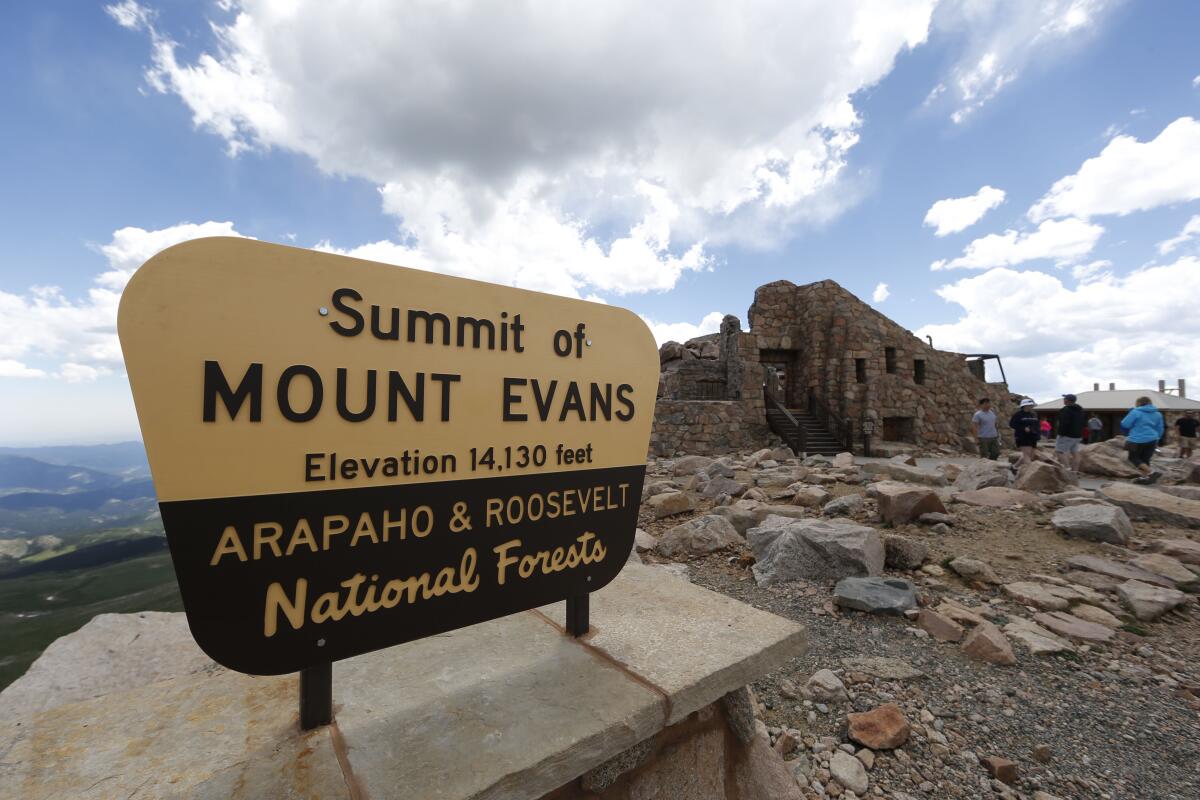

DENVER — A Colorado state panel has recommended that Mt. Evans, a prominent peak near Denver, be renamed Mt. Blue Sky at the request of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes.

The Colorado Geographic Naming Advisory Board voted unanimously for the change. Colorado Gov. Jared Polis will weigh in on the recommendation before a final decision by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names.

Thursday’s vote comes as part of national efforts to address a history of colonialism and oppression against Native Americans and other people of color after protests in 2020 called for racial justice reform.

The proposed name change recognizes that the Arapaho were known as the Blue Sky People, and the Cheyenne hold an annual renewal-of-life ceremony called Blue Sky.

The 14,264-foot peak southwest of Denver is named after John Evans, Colorado’s second territorial governor. Evans resigned after an 1864 U.S. Cavalry massacre of more than 200 Arapaho and Cheyenne people — most of them women, children and elderly people — at Sand Creek, in what is now southeastern Colorado.

Fred Mosqueda, a member of the Southern Arapaho tribe and a Sand Creek descendant, said during Thursday night’s meeting that when he first realized Mt. Blue Sky was a possible alternative, it “hit me like a bolt of lightning. It was the perfect name.”

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis has rescinded a 19th century proclamation that called for citizens to kill Native Americans and take their property.

“I was asked once, ‘Why are you so mean to the name Evans?’” he recalled. “And I told them, ‘Give me one reason to be nice or to say something good. Show me one thing that Evans has done that I as Arapaho can celebrate.’ And they could not.”

Mosqueda, who has been actively involved in Mt. Evans’ renaming process, said Evans was in the perfect position as territorial governor to give the tribes a reservation, but “instead he went the genocide route.”

Polis, a Democrat, revived the state’s 15-member geographic naming panel in July 2020 to make recommendations for his review before they are forwarded to the federal group.

Last year, the federal panel approved renaming another Colorado peak after a Cheyenne woman who facilitated relations between white settlers and Native American tribes in the early 19th century.

In at least one place with the offending name — the unincorporated town of Squaw Valley near Kings Canyon National Park — discussions about what the name should be have already grown heated.

Mestaa’ėhehe Mountain (pronounced “mess-taw-HAY”) honors and bears the name of an influential interpreter, also known as Owl Woman, who mediated between Native Americans and white traders and soldiers in what is now southern Colorado.

The mountain 30 miles west of Denver had been known as Squaw Mountain. Its renaming came after U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the nation’s first Native American Cabinet official, formally declared “squaw” a derogatory term and announced steps to remove it from federal government use and replace other derogatory place names.

“Squaw,” which is derived from the Algonquin language, may once have simply meant “woman.” But over generations, the word transformed into a misogynist and racist term to disparage Indigenous women.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.