WASHINGTON — The relationship between Israel and its closest and most reliable ally, the United States, has started to feel like a case of unrequited love.

Despite being sidelined repeatedly by Israel over the last year, the Biden administration keeps up its nearly unquestioning support — even as Israel all but ignores American efforts to contain the violence and rein in its behavior.

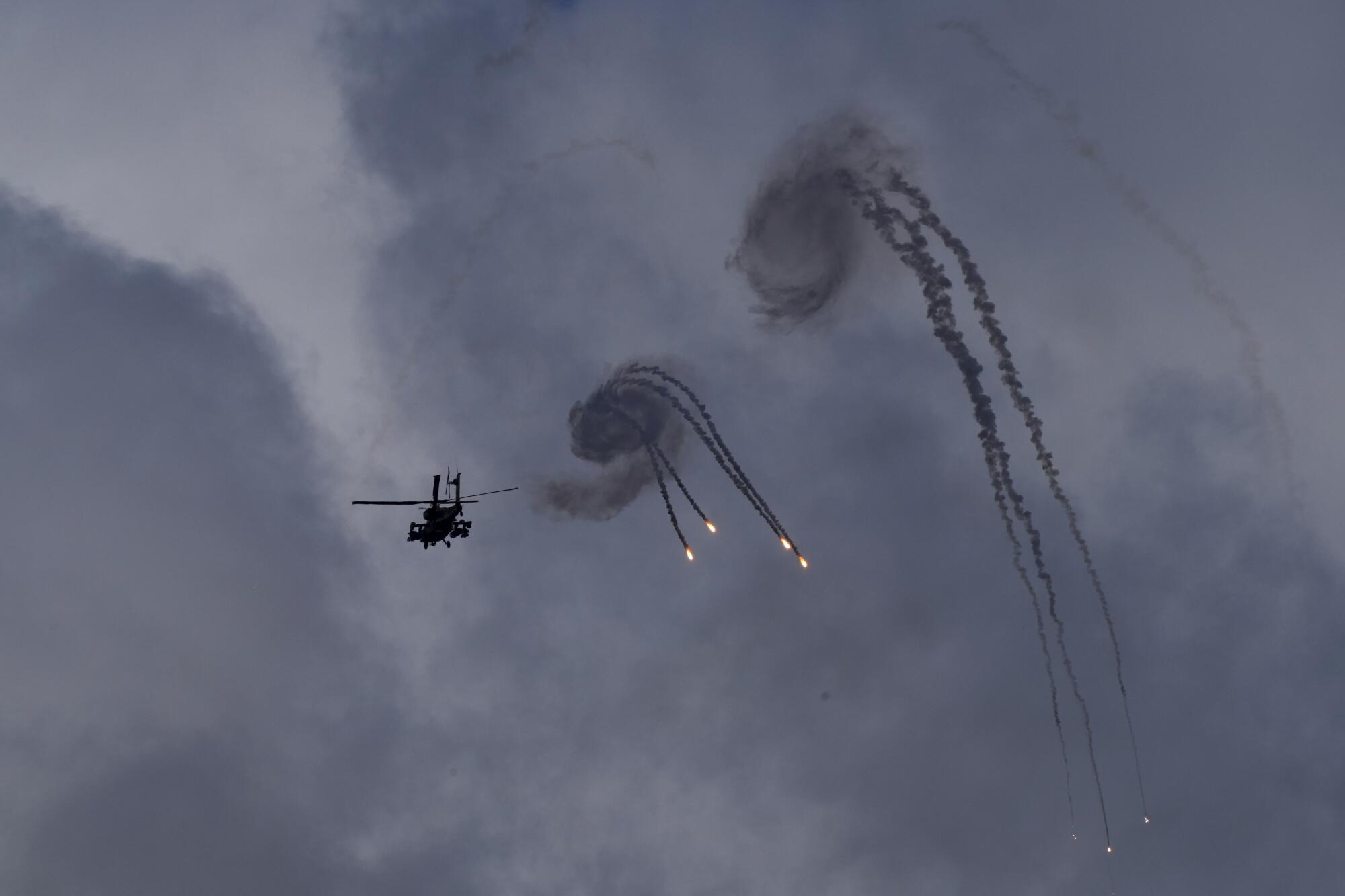

This week, the U.S. government is publicly backing Israel’s march into southern Lebanon, the first such incursion in nearly two decades. The U.S. also supports Israel’s anticipated retaliation against Iran after Tehran’s bombardment of its archrival this week. Both actions could easily push the region into all-out war, a conflict Washington says it doesn’t want.

U.S. officials insist they are working to avert a wider war. But they have little to show for the effort so far. It wasn’t always so hard.

The United States gives Israel around $3 billion a year in aid and much of it in weapons: 2,000-pound bombs, sophisticated air-defense systems, even ammunition. The two countries have long shared intelligence, political goals and foreign policy agendas, and successive U.S. administrations have had considerable sway over Israel and its decisions that had global effects.

That ability appears to have waned in the last year, for a variety of reasons, some less obvious than others.

The unprecedented scale — and horror — of the Oct. 7 attack is one.

A year ago, Hamas-led militants based in the Gaza Strip swept into southern Israel, killing around 1,200 people, maiming many more and kidnapping around 250.

Before that, the Biden administration had kept its distance from the government of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu because of its radically racist anti-Arab, anti-democratic members. Netanyahu had also been exploiting U.S. partisan politics in recent years, openly courting GOP favor and eschewing the usual Israeli policy of staying neutral in American politics.

After Oct. 7, there was a outpouring of support from the United States. President Biden hopped on Air Force One to pledge American backing. U.S. Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken, evoking his own Jewish faith, traveled to Israel 10 times in as many months, trying to address concerns and contain the potential violence.

Netanyahu appears to have read that early administration response as a near-blanket endorsement for an open-ended invasion of Gaza. More than 41,000 Palestinians have been killed in that assault, Gaza officials estimate. The authorities do not differentiate between civilian and combatant deaths.

“The Israelis saw this as essentially a green light,” said Steven Cook, a senior fellow specializing in the Middle East at the Council on Foreign Relations.

At the same time, Israelis, and particularly Netanyahu, have increasingly resisted pressure and advice from the Biden administration when it comes to dealing with Palestinians and other perceived security threats, exerting greater independence.

“Over a period of time, the Israelis have come to believe that the administration has not given them good advice [and] they are determined ... to change the rules of the game,” Cook said.

Increasingly emboldened, Netanyahu repeatedly outplayed and misled U.S. officials, according to people with knowledge of talks aimed at halting hostilities and freeing Israeli hostages.

After having laid waste to much of northern and central Gaza, Israel promised U.S. officials it would not do the same in the southern city of Rafah, where a million Palestinians were sheltering.

Yet as each day passed in the spring, Israeli airstrikes gradually chopped away at Rafah. In recent months, U.S. officials say Netanyahu backed out of cease-fire agreements for Gaza even as some of his spokespeople, such as Ron Dermer, who has the ear of U.S. officials, said Israel was on board.

Just last week, Biden administration officials frantically sought a 21-day cease-fire in Lebanon, backed by France and others. They thought they had secured Israel’s agreement.

Then Netanyahu landed in New York for the annual United Nations General Assembly and made clear he would press ahead unfettered in his offensive against the Iran-backed Hezbollah organization in Lebanon.

In turning a deaf ear to U.S. entreaties, Netanyahu seems to be taking advantage of Biden’s emotional affinity for Israel and of the political timing that ties the lame-duck president’s hands.

Biden is among the last of the old-school U.S. congressional lawmakers who were reared in the post-Holocaust period where an emerging Israel struggled for its survival against greater Arab powers and won. It seemed a noble cause, and Biden frequently has expressed his undying love for the “Jewish state.”

Fast forward to this season just weeks away from a monumental U.S. presidential election, and Netanyahu probably calculates that Biden will not move forcefully to make demands on Israel when it could cost the Democratic ticket votes in a razor-edge close vote.

“American leverage, and Biden’s leverage in particular, is very small at this point,” said Rosemary Kelanic, a political scientist specializing in the Middle East, now at Defense Priorities, an antiwar Washington advocacy group.

“Politically, it’s really difficult to do anything that seems like it’s changing American foreign policy right before an election,” she said.

Even the most minimal challenges to Israel — such as sanctions on Jewish settlers in the occupied West Bank who kill and harass Palestinians, or the brief suspension of 1-ton bombs being lobbed on Gazan population centers — have generated backlash from the Republican right wing.

“We call on the Biden-Harris administration to end its counterproductive calls for a cease-fire and its ongoing diplomatic pressure campaign against Israel,” House Speaker Mike Johnson said after Israel assassinated Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah.

By moving aggressively in Lebanon now, Israel may be betting it can operate more freely in the political vacuum created by the U.S. election.

“I see the Israelis pushing to change the facts on the ground as much as they can” before the U.S. election, said Mike DiMino, a longtime CIA analyst based in the Middle East.

In addition to potentially occupying southern Lebanon while the U.S. is preoccupied with an election, Israel could also force the next U.S. president to confront a regional conflict that also involves Iran, experts say.

Netanyahu “has long wished for a big military escalation with Iran that would force the Americans to join, and perhaps to attack Iran directly,” Dahlia Scheindlin, a fellow at the Century Foundation, wrote in the liberal Israeli newspaper Haaretz. “The circumstances are ripening in a way they never have before.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.