Ex-security czar gets life term as China graft trial comes to quiet end

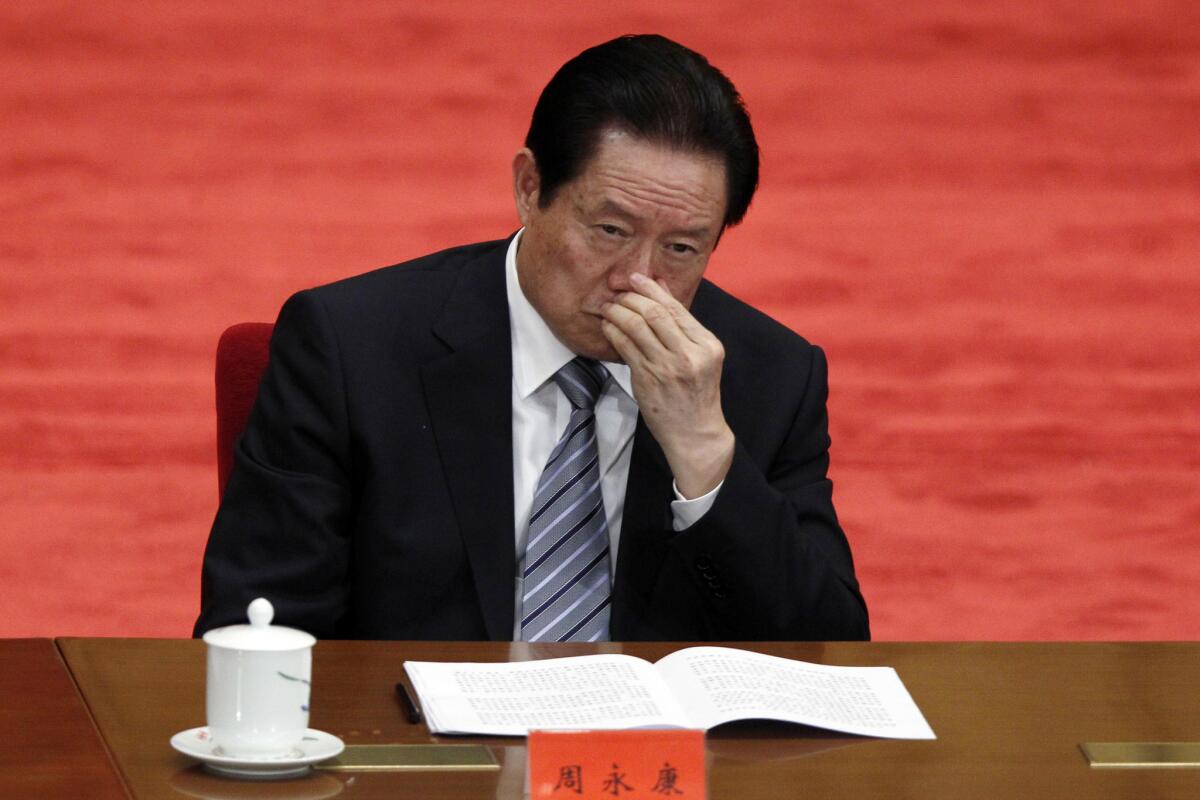

Zhou Yongkang attends a conference in Beijing on May 4, 2012.

Reporting from Beijing — After nearly two years of intense speculation and secret investigation, Chinese authorities said Thursday that former domestic security czar Zhou Yongkang had been sentenced to life in prison on corruption charges after a closed-door trial last month.

Zhou was handed a life term for accepting $21.3 million in bribes, abusing his power and deliberately disclosing state secrets, the Tianjin Municipal No. 1 Intermediate People’s Court ruled, according to the state-run New China News Agency. Zhou was also deprived of his political rights for life and had his personal assets confiscated.

In contrast to the high-profile 2013 corruption trial of former Chongqing party secretary Bo Xilai, Chinese authorities had not publicized the fact that Zhou had even been put on trial.

Zhou, 72, retired from the Politburo Standing Committee in 2012, and its past and present members have long enjoyed an informal immunity from prosecution. Zhou is the highest-ranking Chinese official to be prosecuted since the 1970s.

President Xi Jinping is in the midst of a far-reaching anti-graft campaign and has vowed to ensnare both “tigers and flies” -- officials of both high and low rank -- with Zhou being an exceptionally large “tiger.” Recently, though, speculation has grown that the campaign has stalled, slowed or shifted to focus more on “flies.”

Though the anti-corruption campaign has enjoyed strong public support, Communist Party leaders have not yet adopted institutional changes, such as rules on disclosing assets, that might serve as curbs on graft.

Zhang Lifan, a prominent party historian in Beijing, called the sentence a “compromise” and said it signaled a temporary halt to the anti-corruption campaign as the party starts to prepare for its next major congress in 2017.

“The anti-corruption campaign has faced a great deal of pressure within the party and the leadership is in danger” if it pushes things any further, Zhang said. He called the quiet end to a potentially explosive case a “win-win” for Zhou and the party.

“Zhou Yongkang used to control the key department and knows many people’s secrets, both economic as well as personal secrets. Since he has these secrets, he was able to negotiate a better deal for himself,” Zhang said. At the same time, “the party’s face is saved.”

But Clayton Dube, head of USC’s U.S.-China Institute, said the way the verdict was handled shows China’s party-state is still uncomfortable with transparency.

“While it has become more open than in the past, China’s leaders still prefer to announce results rather than to welcome audiences to view the processes of decision-making,” he said. “The party-state wants to show it polices itself. ... But it doesn’t want to fully explore wrongdoing for fear of signaling how long officeholders get away with corruption and how far-reaching it may be.”

According to the news agency, Zhou’s case was heard May 22 and was not open to the public because it involved disclosure of state secrets. Zhou pleaded guilty and will not appeal, the agency said. In video shown on state-run CCTV, Zhou appeared thinner and significantly older, his hair, long dyed jet black in the style favored by Chinese leaders, gone totally white.

Zhou abused his power and deliberately disclosed state secrets “in particularly grave circumstances” and took “particularly huge bribes,” a statement from the court said, but his action “did not have serious consequences.”

The court said Zhou instructed two associates to “assist” the business activities of others, helping them to illegally obtain about $350 million and causing losses to the state of $250 million.

Zhou leaked five “extremely confidential” documents and one “confidential” document to an unauthorized person identified as Cao Yongzheng, in violation of the State Secret Law.

Cao has been described in some overseas Chinese-language media reports as a self-styled master of the Chinese martial art of qigong who claimed to be able to predict the future. His energy company, some reports said, received illicit gains through his associations with the Zhou family.

According to the news agency, Zhou’s wife, Jia Xiaoye, and son, Zhou Bin, testified through video link while other witnesses appeared in court.

In its statement, the court said Zhou Yongkang had confessed truthfully, pleaded guilty and repented his wrongdoing.

The court added that most of the bribes were accepted by Zhou’s relatives, without his knowledge, and that Zhou asked his family to return their illegal gains.

Because “all gifts and cash have now been recovered,” the news agency reported, the court decided those actions constituted “legal and discretionary grounds for lesser punishment.”

The news agency quoted Zhou as saying that “the basic facts are clear. I plead guilty and repent my wrongdoing. ... Those involved, who bribed my family, were actually coming after the power I held, and I should take the main responsibility.

“I broke the law and party rules incessantly, and the objective facts of my crimes have resulted in grave losses of the party and the nation,” it quoted him as saying.

Zhou’s arrest was disclosed in December, and he had already been expelled from the Communist Party.

Zhou’s 2012 retirement as a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, the highest body in the Communist Party, came just as Xi was elevated to party general secretary. Xi became China’s president in March 2013.

Zhou was long feared and loathed by Chinese liberals, who accused him of excesses against dissidents. He also was widely believed to have fostered rampant corruption in the state-run oil sector, where he was an official early in his career.

Some analysts believe that a power struggle at the apex of the Communist Party led to Zhou’s downfall. According to this line of thinking, he was part of a political faction, which also included Bo and former President Jiang Zemin, that posed a serious rivalry to Xi.

During Bo’s trial, testimony emerged that the domestic security apparatus, then under Zhou’s control, had tried to cover up the killing by Bo’s wife of a British national, Neil Heywood, with whom she had a business dispute.

Some claimed that Zhou’s attempts to shield Bo, a protege, amounted to insubordination or even constituted a coup attempted against the leadership.

The Communist Party’s investigation of Zhou was conducted out of the public eye, and his name had been essentially off-limits in Chinese media for more than a year.

Reports in overseas Chinese media said the investigation of Zhou began as early as August 2013. The New China News Agency said in December 2014 that the Politburo Standing Committee had heard a report on his case in December 2013 and reviewed the investigation by the party’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection in July 2014.

Zhang, the historian, said the party had been eager to avoid another spectacle like the Bo trial.

“Bo had more political resources and connections, he was one of the princelings and a party political star,” Zhang said. “Zhou Yongkang was a grass-roots official and when he was an official, people feared and hated him.”

“So when he was removed, there was not much sympathy. To avoid the embarrassment and lack of control as in Bo’s trial, Zhou’s went on discreetly and finished very quickly. The [state-run] media even had a ready-made package to show to the public very quickly, and this shows they were well prepared.”

Follow @JulieMakLAT for news from China

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.