Even Bollywood’s protests are over the top: Hindu mobs burn cars, threaten beheadings to block a movie in India

Reporting from MUMBAI, India — Movie producers crave pre-release buzz, but what’s happened with the latest Bollywood epic has been excessive.

A fringe Hindu group vandalized a film set and assaulted the director. They torched cars and pelted a school bus with stones as children cowered behind their seats, and hundreds of members threatened to set themselves on fire. One supporter called for the director and lead actress to be beheaded.

And all this before the movie was even released.

“Padmaavat” on Thursday finally arrived in theaters, although not nearly as many as producers had hoped. Cinema owners in several states declined to screen the big-budget movie — the tale of a mythical Hindu queen who walked into a funeral pyre to avoid capture by a Muslim conqueror — for fear of inciting mobs.

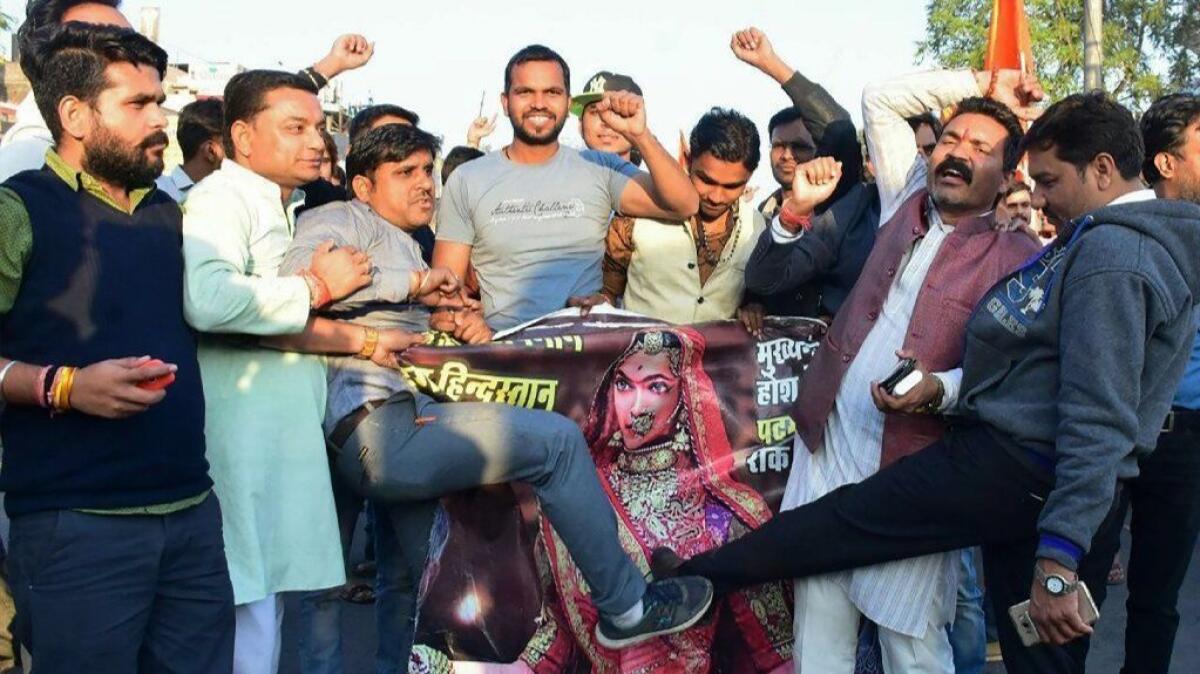

Those worries were well-founded, as scenes of chaos played out across India on the film’s debut day. Mobs burned director Sanjay Leela Bhansali in effigy, blocked highways with burning tires and brandished swords at rallies in northern India while phalanxes of police officers were deployed outside cinema halls in Mumbai, New Delhi and other cities.

Unrest has raged for weeks, driven by Hindu extremists who objected to a love scene between the 14th century Muslim ruler Alauddin Khilji and the Hindu queen, Padmini. The queen is a legendary figure to Rajputs, a caste that descends from northern Indian warriors, even though the story is based on a 500-year-old poem and most historians believe she never existed.

Except, according to Bhansali, there is no such scene in the movie. The studio, Viacom 18 Motion Pictures, released a statement saying the film — at about $30 million, one of the most expensive made in India — “captures Rajput valor, dignity and tradition in all its glory.”

But rumors that the film besmirched the Rajputs’ honor did not die, egged on by leaders of a fringe group known as the Rajput Karni Sena.

Last January, its followers stormed a historic fort in northern India where the movie was shooting and roughed up Bhansali and his crew. The group also threatened to chop off the nose of actress Deepika Padukone, who plays the queen.

This month, one leader of the group in the northwestern state of Rajasthan claimed that 1,900 women had signed up to immolate themselves — in the manner of the fictional queen — if the movie wasn’t banned.

Producers delayed the original Dec. 1 release date, slightly altered the title and added a disclaimer that the film does not claim historical accuracy. India’s Supreme Court then got involved, ruling that states could not block the film because authorities had an obligation to ensure security.

Still, the Multiplex Assn. of India, an industry body that represents most major theaters nationwide, said this week that its members in four states would not show the movie “in view of the prevailing law and order situation.”

“What’s paramount for us is the safety of our patrons and the safety of our employees,” the association’s president, Deepak Asher, said in an interview.

“We are reviewing the situation on an hourly basis, and if and when we find that the circumstances are conducive, we could open the film. But at this point, we don’t see that happening.”

The Supreme Court said it would take up cases next week against Karni Sena members and against four state governments for failing to control demonstrators. All four — Gujarat, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Haryana — are led by India’s most powerful political party, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP, a Hindu nationalist organization.

Critics have questioned why state officials were unable to maintain order and accuse Modi’s allies of coddling right-wing Hindu extremists. One BJP official in Haryana, Surajpal Amu, was reportedly placed under house arrest Thursday for comments he made in November, when he put up a $1.5-million prize for chopping off the heads of Bhansali and Padukone.

“It is beyond horrible,” Tavleen Singh, a columnist who supports Modi, wrote on Twitter. “Why is there such a collapse of law and order in BJP states? Shame on the chief ministers who are allowing this to happen. Speak up please, Prime Minister.”

Modi was at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, this week, touting his country as a model of globalization and economic progress. The contrast with the disorder at home — in some of India’s most economically developed states — drew scorn.

“We are self-delusional if we think we’ve arrived at the global high table,” tweeted Nirupama Menon Rao, a former Indian ambassador to Washington.

India might be home to the world’s most prolific film industry, but protests by Hindus — by far the country’s largest faith group — have sometimes derailed movies that hardliners accuse of insulting their religion.

In 1998, Hindu extremists attacked theaters showing the Deepa Mehta film “Fire” for depicting a lesbian relationship. Two years later, vandals destroyed film sets for Mehta’s follow-up feature, “Water,” which they said promoted relations between high-caste Hindus and “untouchables,” the lowest rung of the ancient caste hierarchy.

As middling reviews of “Padmaavat” roll in, some critics have pointed out that the film glorifies the Rajputs’ battlefield successes — despite historical evidence to the contrary — while portraying Khilji, a Muslim, as an evil outsider. When the film was screened Wednesday for Rajput leaders in the northern state of Punjab, one said afterward that he’d found “nothing objectionable.”

“What logic then for the curiously hurt Rajput pride when all the film does is singularly exalt the community,” film critic Namrata Joshi wrote in the Hindu daily.

The other irony, Joshi wrote, is that for all the drama in the streets, the lavish saga onscreen comes off as ponderously dull.

“If there’s one disclaimer that ‘Padmaavat’ should have rightfully sported,” she said, “[it] is, ‘Any lapse into boredom is purely unintended.’ ”

Special correspondent Parth M.N. contributed to this report.

Follow @SBengali on Twitter for more news from South Asia

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.