Charlie Hebdo’s survivors, amid tears and debate, focus on next edition

Reporting from Paris — Days after the massacre that shocked this nation, the surviving staffers of French humor magazine Charlie Hebdo are gathered in another newsroom planning their next edition.

What is usually is the most ordinary of tasks for any journalist is now taking place under the most extraordinary of circumstances.

There is the personal element of mourning slain friends, worrying about comrades still hospitalized. There is the debate about whether the staff of a magazine that is fiercely anti-establishment should participate in the weekend’s public memorials led by the kind of government bigwigs they typically ridicule.

At the same time, a magazine that has struggled financially to survive most of its 3 1/2 decades of existence finds itself the recipient of an almost unthinkable financial windfall from a wide range of groups that seems to guarantee it a long, sustainable future.

Amid this whirlwind of moments rife with contradictions and conflicting emotions, the staff must collectively answer the same question that has faced them for so many years:

What to write and draw about this week — and how to write and draw it?

“We have a paper to create, with a lot fewer people than before, in conditions you are all aware of,” Richard Malka, the magazine’s lawyer, told reporters. “The remaining strength we have, the heart we have, we will be putting it into our upcoming eight pages. It has always been our way of expressing ourselves, so that is what we’ll do.”

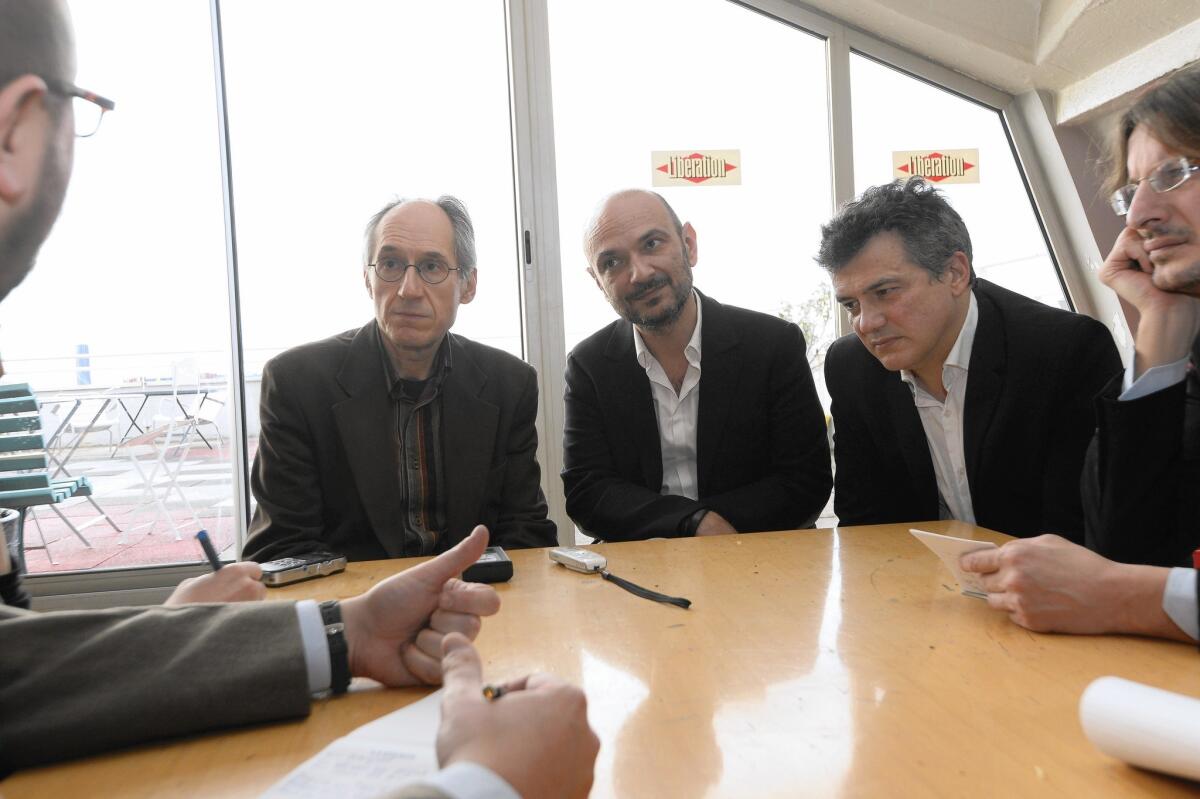

The Charlie Hebdo staff has been gathering on a top floor in the offices of progressive French newspaper Liberation. The offices are in a plain-looking building just a block from the Place de la Republique, which has become a rallying place for mourners and tributes since the shootings Wednesday a few blocks away.

Johan Hufnagel, a managing director and editor of Liberation, said the offer to lend space to the Charlie Hebdo staff was made shortly after the scope of the shootings was clear.

The staffs have shared some writers over the years, and Charlie Hebdo also temporarily worked out of Liberation’s offices in 2011 after its offices were firebombed. No one was arrested or claimed responsibility in that case, although the attack took place just days after the magazine published an issue entitled “Charia Hebdo” — a play on sharia, or Islamic law — with a cartoon of “guest editor” Muhammad on the cover.

“They are like our brothers, our cousins,” Hufnagel said. “It was obvious they would come here, like coming home.”

Because the staffers want privacy to get on with their work, they have generally declined interview requests. However, Liberation has been posting articles and videos giving glimpses of the staff meetings each day.

“They needed to be all together in a closed space, because we knew there would be a lot of crying and tears,” Hufnagel said. “And we needed somewhere to protect them from the madness of the world.”

At one point Thursday, according to the dispatches and videos, the staff discussed colleagues who had been injured in the previous day’s shooting rampage and remain hospitalized, including the magazine’s webmaster, who had to be placed in an artificial coma and another who had been shot in the jaw.

As one woman collapsed in tears, according to the Liberation account, editor-in-chief Gerard Biard comforted her and said, “You do not have to feel guilty!”

Later, the staffers got down to the business of trying to figure out what to write and draw to fill the eight pages of an edition that will print 1 million copies on Wednesday. They quickly dismissed the notion of doing a tribute to their colleagues, but ... then what?

The sessions were interrupted by a visit from Prime Minister Manuel Valls and Minister of Culture and Communication Fleur Pellerin, sporting “Je Suis Charlie” (I Am Charlie) stickers.

The praise from representatives of a government the magazine has skewered mercilessly is almost as strange as the memorials from religious institutions the magazine derided for years. On Friday, the Paris City Council awarded the staff a rare honorary citizenship of the capital for being “distinguished great resistance fighters against dictatorship and barbarism.”

Later, Pellerin pledged about $1.2 million to support Charlie Hebdo.

France will always stand “alongside the defenders of freedom of information and expression,” Pellerin said in a statement. “We will defend these values with the necessary firmness.”

That money comes on top of pledges of equipment and staff from other French media, plus nearly $600,000 donated by publishers and a new media fund supported by Google, and $150,000 pledged by London’s Guardian Media Group. In addition, a crowdfunding campaign has raised more than $100,000.

For a publication that concluded 2014 in the kind of dire financial crisis that had dogged it for most of its existence, it is a windfall both unimaginable and, well, awkward.

“I know it has made them very uncomfortable,” Hufnagel said. “They are very independent and they don’t like to be dependent on anyone.”

Also, their efforts got a boost when Albert Uderzo, 87, a legendary French illustrator, announced that he would come out of retirement to draw for the magazine this week. Uderzo is creator of Asterix, a fictional warrior in ancient Gaul fighting the occupying Romans.

“I just wanted to show my friendship for the cartoonists who paid with their lives,” Uderzo said in an interview on Europe 1 radio. He also drew a cartoon of Asterix punching a man who appears to be Arab and saying, “Me too, I’m a Charlie!”

In the Liberation offices, staffers have gathered around computers for debates. One artist can be seen drawing a cartoon of what appears to be man wearing a turban, yelling and shaking a fist. Another picture stuck on a wall shows a fist with a pencil held like a raised middle finger.

“At the beginning, we embraced and it was emotional,” designer Renald “Luz” Luzier said in a video. “We then tried to find the cover, and we did the same thing we always did ... the Wednesday before the crisis. And we decided to do a paper like we always do.”

O’Brien is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.