As resources run dry, Syrian refugees cling to survival in Jordan’s urban hubs

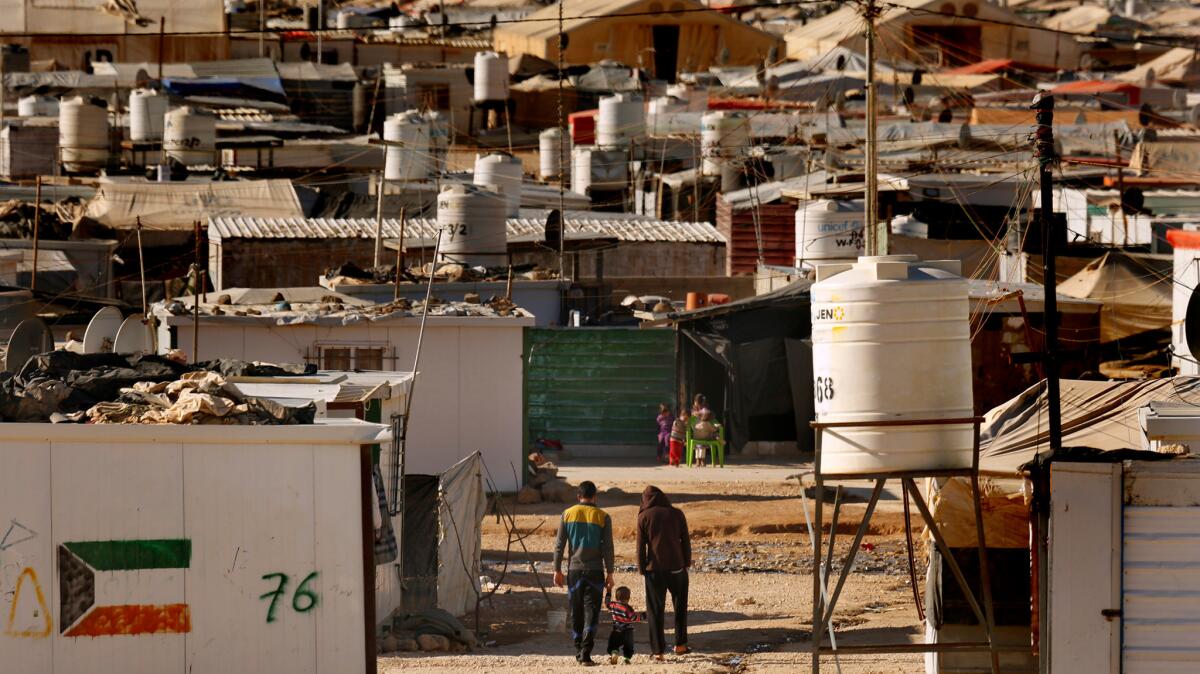

Reporting from Rusaifa, Jordan — Four hours at the Za’atari refugee camp — a stifling, dusty maze of tents and makeshift shelters 30 miles from the Syrian border — was enough to convince Abd Mawla Juma’a that his family had to move on.

“There was no way we could stay in the camp,” said Juma’a, 37, who fled his home in Syria four years ago with his family.

Juma’a contacted a relative in Jordan who helped him find a small two-room house in Rusaifa, a hardscrabble industrial city northeast of Amman. In the winters, the family huddles in a single room; in the summer, scorpions and other insects invade the building. His terrified children skirt snakes that coil up by the front door.

Immobilized after back surgery for an injury he suffered fixing windows and doors, Juma’a has not been able to pay the rent in four months. He agonizes over what will become of his family.

Once, when he was part of Syria’s middle class, when he owned a car and a store that sold makeup and perfume, when he lived in a comfortable home, the future seemed guaranteed.

Not any more.

“I feel guilty that my children have needs but I’m unable to provide,” said Juma’a, who has an 11-year-old son, Rami; twin 9-year-old boys Mohammad and Ahmad; and a 6-year-old daughter, Bana. “I have no hope.”

Of the 670,000 Syrians registered with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Jordan, the vast majority — around 85% — live outside the relative security of refugee camps, where they don’t have to worry about paying for rent or utilities.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj »

Instead, they’ve found assorted housing in cities and towns, often in squalid conditions. For many, their existences are becoming increasingly desperate as time passes, resources run dry and the hospitality of their host nation wears thin.

“It’s getting worse and worse,” said Paul Stromberg, UNHCR’s Amman-based deputy representative. “Many people did not expect to stay here that long.”

Three-quarters of the Syrian refugees are in debt, owing an average of $1,038, according to U.N. data, while 93% are living on less than $88 per month, per person.

About half buy food on credit or borrow money to purchase food, said Aoife McDonnell, a Jordan-based spokeswoman for the refugee agency. And around a third have not paid rent in months, living with the risk of eviction, U.N. data show.

Still, most Syrian refugees prefer the urban setting to life in a camp — though harsh winters and lack of rent money have forced some back to the refugee settlements.

“We want to ensure no one is driven back to Syria because they could not afford a roof over their heads,” Stromberg said.

UNHCR provides cash assistance — around 130 Jordanian dinars a month (equivalent to about $183, depending on the exchange rate) for a family of five — to the most vulnerable out-of-camp refugees, agency officials said. But once the rent is paid, there’s little left over.

Juma’a’s rent is about $155 a month. He used to be able to pick up odd jobs to help pay it, but the back injury ended that.

His wife, Nahla Kahled Melhem, 34, said she buys rice, flour and other rations with U.N.-issued food coupons worth around $14 a month for each family member.

When he could work, Juma’a said, the police threatened to jail him when he was caught without the proper permit.

Work permits cost between $170 and $1,270, depending on the job. And although employers are responsible for securing permits, sometimes they transfer that burden to the would-be worker, said Anna Gaunt, a UNHCR livelihoods officer in Amman.

A grace period that allowed some employers to get free work permits for Syrian refugees is set to expire in early October, a deadline that could leave some refugees trying to work illegally, putting themselves at risk of being exploited and shortchanged on their wages.

The predicament has forced many refugee children into the labor market, according to UNICEF. A survey of households by the agency last year found that nearly half of all Syrian refugee children in Jordan are now the joint or sole family breadwinners. Some, though, turn to illegal activity, such as organized begging, and sometimes fall victim to child trafficking, according to UNICEF.

More than a third of the Syrian refugee children did not attend school last year — the majority in Jordanian towns and cities, according to Human Rights Watch, which cites data from the U.N. and the Jordanian Education Ministry.

Some 50,000 children have been out of school for more than three years, the rights agency said. The Jordanian government recently announced plans to enroll all Syrian children when the new school year starts this fall, even if they lack previously required documents, according to local media reports.

Juma’a and Melhem’s sons attend class, but she worries about the quality of education at a local school where Jordanian students are taught in the morning and refugee children in the afternoon.

“They aren’t taught well,” Melhem said. “The teachers don’t pay attention to the refugee children. I wish they were integrated with the Jordanian children.”

Some days her sons are left alone in class and allowed to do as they please, she said. At other times, they are allowed to play sports all day. Her twins can barely read.

“My biggest fear is for my sons, for their basic learning,” said Juma’a, who wishes the family could join relatives in the U.S. or Canada. “If they don’t get a proper education they will lose everything … their future.”

Melhem also expressed concern that her sons were becoming rowdy and wayward, influenced by the boys they hang out with in the tough neighborhood they call home.

“I’m afraid I’m losing control of my sons,” Juma’a said.

As the Syrian refugees have poured in, there’s a sense that Jordan’s hospitality is being strained.

The World Bank estimates that the influx of Syrian refugees has cost Jordan more than $2.5 billion a year, or one-fourth of the government’s annual revenue. The burden adds to the cumulative strain the country has endured as a result of taking in refugees from the Palestinian territories and more recently Iraq over the last two decades.

“Syrians are being blamed for crime and the decrease of the economy,” said Milia Eidmouni, regional director for the Syrian Female Journalists Network and herself a former refugee, who has documented an increase in hate speech against Syrian refugees on the Internet.

Increased demand for already scarce housing in lower-income neighborhoods has caused rents to skyrocket, with landlords inflating their prices by 200% and sometimes higher, according to a 2014 opinion piece by Ibrahim Saif, the country’s minister of planning and international cooperation, in the Jordan Times.

Together with overcrowded schools, the influx of Syrian refugees is straining an already overburdened and poorly resourced healthcare system, as more than half a million refugees seek medical attention alongside Jordanians, aid officials said.

Complaints also abound that Syrians are causing wages to drop in certain sectors because of their willingness to accept less pay — often because they don’t have a work permit and cannot protest their salary. Syrians’ ability to work in addition to receiving food vouchers and financial assistance from aid organizations has also sparked resentment.

Jordanians feel that “all the attention is being paid to Syrians and poor Jordanians are being neglected,” said Layla Naffa Hamarneh, director of projects for the Arab Women Organization of Jordan in Amman.

“Jordanians envy Syrians,” she said.

But families like Juma’a and Melhem’s feel they have little that others should covet.

“We have four children with no future… a husband who cannot work,” Melhem said. “How will we live?”

Funding for this report was provided by a grant from the United Nations Foundation

For more on global development news follow me @AMSimmons1 on Twitter

ALSO

A year later, legacy of refugee crisis has Greeks fearing paradise lost

Three bomb blasts hit Kabul, Afghanistan in one day, killing at least 35

Obama vows to tighten sanctions on North Korea after missile launch

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.