Stretching for miles, 7,000-strong migrant caravan treks through stifling heat in southern Mexico

Reporting from Tapachula, Mexico — A growing caravan of roughly 7,000 Central American immigrants continued its trek toward the United States on Sunday, blowing past Mexican police and immigration officials.

The group, which has swelled in size in recent days, set out before dawn on the only road out of the small Mexican border town of Ciudad Hidalgo. It arrived in the afternoon in the city of Tapachula, more than 20 miles away.

The migrants, nearly all from the poor and violent nation of Honduras, posed a growing political and humanitarian calamity for Mexico, which has come under intense pressure from President Trump to stop them.

On Friday, Mexican police used tear gas to block migrants from storming an official border crossing. But in the days since, Mexico has appeared unwilling to use force to stop the thousands of people who have illegally crossed the Suchiate River from Guatemala into Mexico and started walking north.

That may be in part because the migrants include hundreds of women and small children, some in strollers. It could also be because of the daunting size of the caravan, which stretched for at least two miles.

As the caravan headed north Sunday in the 90-degree heat, another group of roughly 1,500 migrants waited on the Guatemalan side of the river, hoping to enter Mexico legally.

Authorities said more than 1,000 caravan members already have entered legally and applied for refugee status in Mexico and are being detained while their applications are processed.

The migrants left Honduras more than a week ago and began arriving several days ago at the Guatemalan border town of Tecun Uman, just across the river from Ciudad Hidalgo.

Most say they intend to cross into the United States, not seek refuge in Mexico. Some complain that they were unable to find work in Honduras. Others say they are fleeing violence or political repression there and hope to apply for asylum in the U.S.

Ingrid Andino, her husband and their two children left their small town in Honduras about a month ago after a local gang started pressuring her 16-year-old son to sell drugs. “They were going to kill him or kill us,” she said.

Andino said her family stayed with relatives in another town for a time before seeing the caravan on the news and deciding to join.

On Sunday, she and her family walked north in a line, holding hands, while she carried a bag containing the family’s possessions balanced on her head.

Trump has made the caravan a campaign issue at rallies across the country ahead of the U.S. midterm elections, calling it a menace to national security. He has threatened Mexico and Central American countries with economic reprisal if they fail to stop the migrants and vowed to send the military to close the U.S. border should the group make it that far.

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto, under pressure from Trump, has said repeatedly that no migrants will be allowed to enter the country in an “irregular” manner. Mexico’s deterrence of those who tried to storm the official border crossing Friday drew praise from Trump.

But when droves of people began crossing the river, swimming or boarding rafts, Mexican police and immigration agents just watched.

Gerardo Hernandez, head of the civil protection agency in the municipality of Suchiate, Chiapas, said that as of Saturday night, 7,233 immigrants had been registered at a shelter in Ciudad Hidalgo.

The group formed an imposing bloc as it began to march Sunday. Many Mexicans who live in the area lined the highway, handing out free clothes, sandwiches and bottles of water while cheering the caravan on.

“May God bless you!” one woman shouted.

“Thank you, Mexico!” the migrants shouted back.

Several times, large groups of police officers clad in riot gear blocked the road but then retreated. At one point, a small group of police watched as members of the caravan passed, some of them skipping.

When a small group of immigration officials tried to stop the caravan to persuade its members to apply for political asylum, the caravan swept past them, too.

As the day wore on, the enthusiasm drained somewhat.

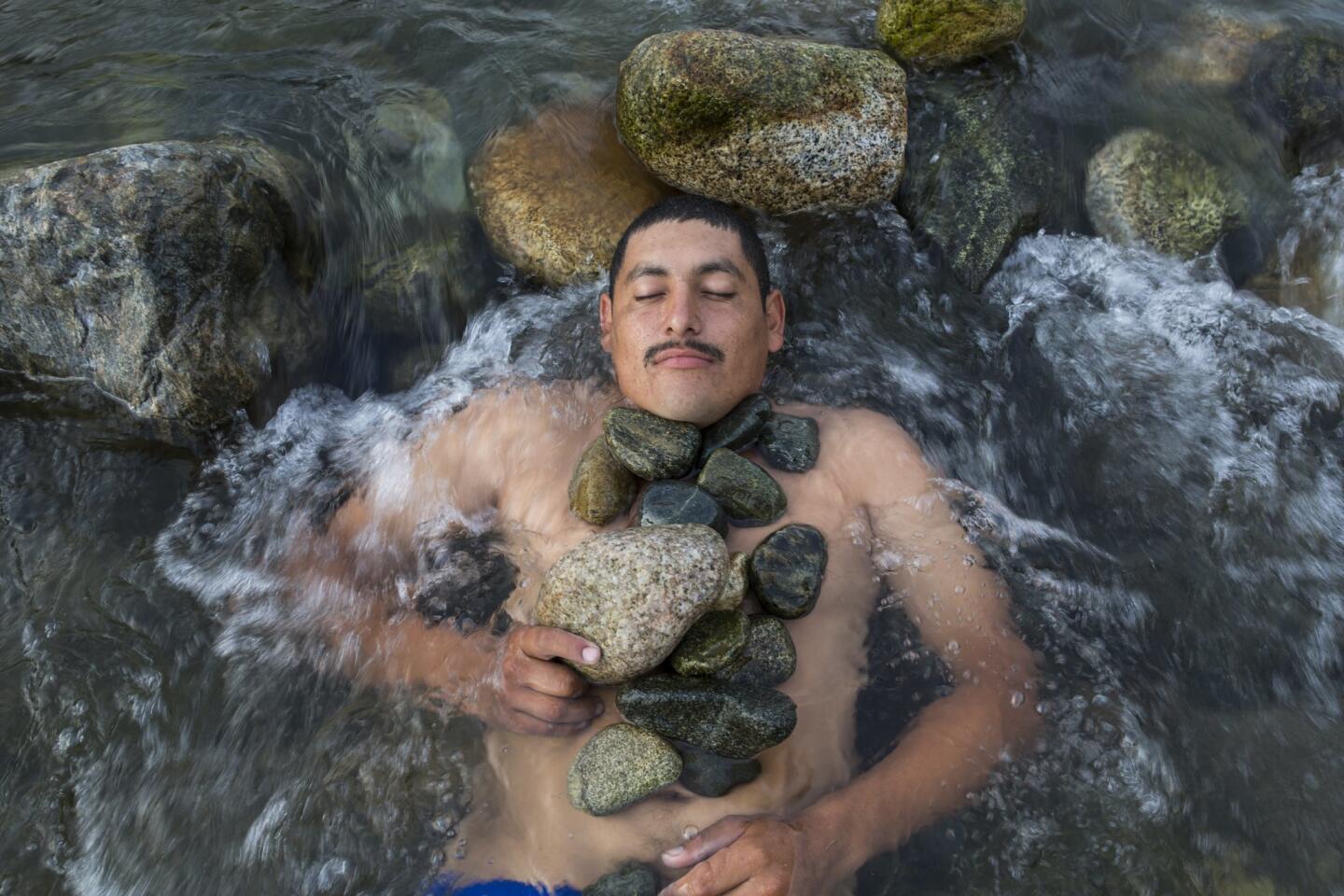

The strongest of the group, mostly young men, led while the weaker fell behind. One teenage girl stumbled into a car parked on the shoulder of the highway, then rested her head for a brief moment on the trunk. Others carried cases of water, stuffed animals or children.

Paola Oviedo, 21, walked while hugging her 18-month-old son to her chest. She was panting, and she and her baby were both sweating heavily.

Oviedo, who crossed the Suchiate River on a raft, said she decided to leave Honduras after facing death threats from her abusive ex-husband. The police did nothing to help her, she said.

She said she didn’t want her son to grow up without his mother.

“I have to do this for his future,” she said.

Each immigrant was driven by a different dream.

For Cesar Meijia, 23, it was the freedom to be himself.

When Meijia came out as gay several years ago, his family sent him to a psychologist and the local gang threatened to kill him, saying they did not want people like him in their neighborhood. “I want to go to a place where people respect me,” he said, marching with a rainbow flag tied across his broad shoulders.

For Ramon Izaguirre, 20, the dream was to return to the life he left behind.

Izaguirre was born in Honduras but later moved to Phoenix with his mother. She cleaned houses while Izaguirre worked construction. He earned enough to buy a small condominium and a silver Mazda Miata.

He said he was was deported about a month ago after a routine traffic stop revealed that a work permit he used to enter the country had expired.

Izaguirre had convinced several friends in Honduras to try to reach the United States with him again.

“All my life is there, waiting for me,” he said in English. “I miss my PlayStation. I miss Buffalo Wild Wings. I miss my car.”

The group walked together Sunday at a quick pace. Izaguirre, dressed in a camouflage shirt from his days in ROTC at a Phoenix high school, led the way. At one point, he started reciting the Pledge of Allegiance.

When a pickup truck pulled up next to the caravan and offered them a ride, Izaguirre and his friends scrambled into the back.

“Let’s go,” he said, and the truck sped off.

Migrants arrived throughout the afternoon in Tapachula, finding their way to a plaza in the city’s colonial-era center.

Denis Omar Contera, an organizer with Pueblo Sin Fronteras, which is helping the group, said the caravan plans to rest Monday before setting out again.

He laughed off claims made by some Republicans that the caravan is being organized by Democrats or political opponents of the right-wing president of Honduras, Juan Orlando Hernandez.

“The only people who have helped us are the poor people of Guatemala and Mexico who have shared with us their beans and tortillas,” he said.

Times staff writer Patrick McDonnell in Mexico City contributed to this report.

Twitter: @katelinthicum

UPDATES:

6:20 p.m.: This article was updated to include the new number of caravan members who have applied for refugee status in Mexico.

5:10 p.m.: This article was updated with political analysis and scenes from the caravan.

9:30 a.m.: This article was updated with the caravan passing police en route to the U.S. and with additional background.

This article was originally published at 7:15 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.