30 years ago a Chinese tank column stopped for ‘Tank Man.’ Fang Zheng wasn’t so lucky

Reporting from Beijing — Everyone remembers China’s “Tank Man,” who stood with bags in his hands, blocking a line of tanks withdrawing from Tiananmen Square a day after the fatal June 4, 1989, military crackdown against pro-democracy protesters.

Thirty years later, Fang Zheng wonders why the tanks stopped for that man, but rolled right over him as he and other students soberly retreated west along Changan Avenue after leaving Tiananmen Square in the early hours of that fateful day.

He remembers his trouser leg getting trapped in the tank’s caterpillar track and the feeling of being dragged along the ground before he managed to wrench himself free. He remembers looking at the mangled bone and blood of his crushed legs.

“I just want to know the truth,” he said in a recent interview.

But Chinese authorities have spent 30 years diligently erasing the truth. Almost no mainland Chinese under age 40 know what happened and older citizens dare not speak of it. China has never released the number of people killed.

For survivors like Fang, the pain and trauma of the day the Chinese army turned on its own citizens is compounded by the knowledge that authorities have succeeded in burying the truth in mainland China — and their hopes for a more liberal, tolerant society have collapsed.

For these participants in the 1989 uprising, the official obliteration of the truth only makes it more crucial to bear witness to what happened.

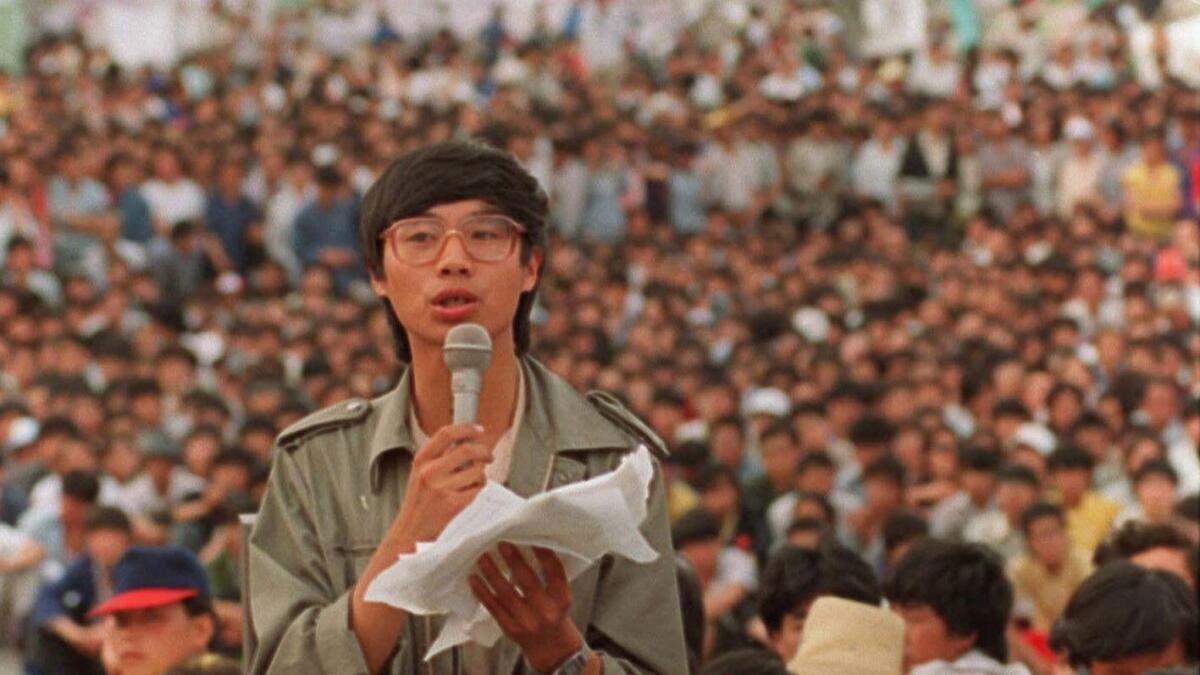

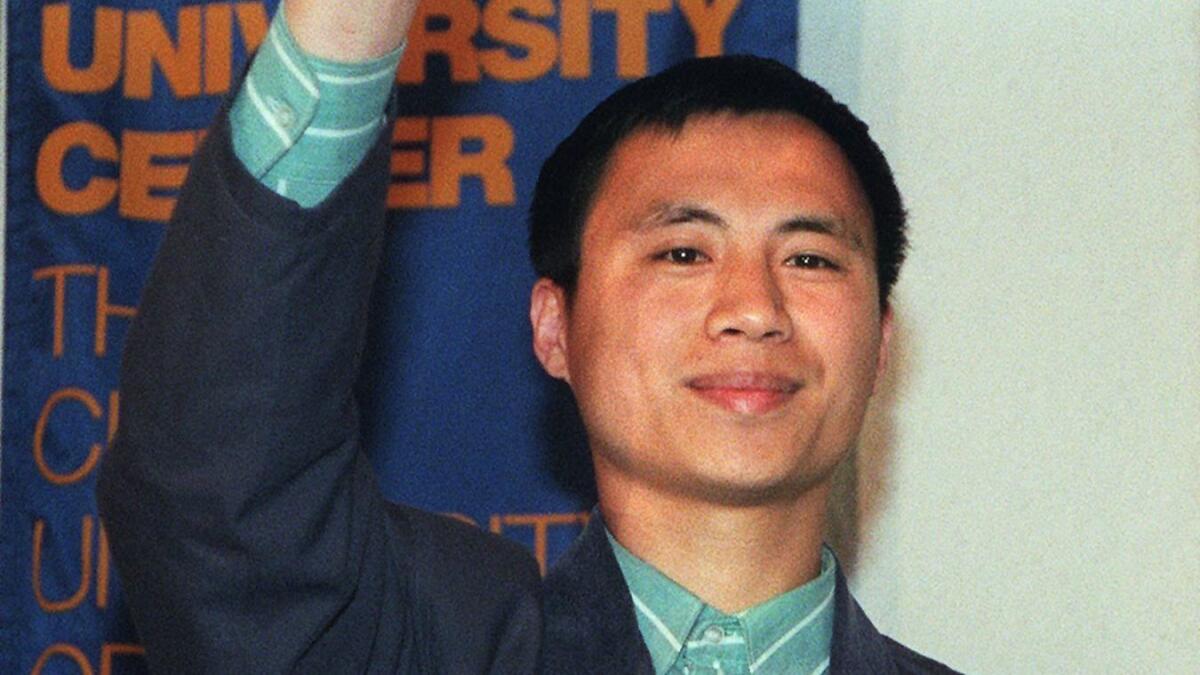

“They have erased all memory of what happened,” said former student protest leader Wang Dan, 50, in an interview. In 1989, he cut a slight figure, wearing oversized glasses and a white headband, often pictured exhorting students through a megaphone.

“As citizens of China we have the right to know what happened,” said Wang, who was exiled to the United States in 1998. “By covering up the truth, they violate their promise to the people. They take our rights away.”

Wang and other dissidents believe Western leaders got China wrong after the crackdown. Eager to profit from China’s vast market, they counted on the Communist Party to loosen its tight political and social control, especially after joining the World Trade Organization.

Those hopes have been dashed since President Xi Jinping’s sweeping human rights crackdown in recent years and his move to abolish term limits last year.

China officially elevates Xi Jinping to level of Mao »

Wang said the students, too, underestimated the government’s capacity for brutality.

“We were naive once, 30 years ago,” he said. “I think the entire world was naive. They had hope that with economic development, China would liberalize. I think some people have now recognized that they created a monster — because China has now become a monster that will challenge the whole world.”

China’s ban on even the vaguest reference to the massacre signals that opposition or dissent is not tolerated. Activists and human rights lawyers are jailed; high-tech digital surveillance keeps dissent in check.

Thirty years on, emotions still run strong for the survivors.

“Of course I’m still angry,” says Wang.

The 1989 pro-democracy movement came at the tail end of a heady decade in which questioning of official policies was tolerated in China and liberal reformer Zhao Ziyang, the party general secretary, opened up the economy and tried to push for political change. When a reformist government leader, Hu Yaobang, died on April 15, 1989, students marched to mourn and press for change.

“Back then there was no internet and no mobile phones. It was difficult to organize and difficult to communicate,” Wuer Kaixi, another student leader, said in an interview. Among his challenges: organizing the first mass march to Tiananmen Square when he had no loudspeaker.

“I yelled with my loudest voice and I told those who could hear me to repeat what I said to those behind,” he recalled.

The students protested corruption and rising prices and called for free speech and the right to protest. Four days later the People’s Daily — the official voice of the Communist Party — sharply condemned the protests. But the next day, April 27, about 100,000 people marched in the first mass pro-democracy protest in China, in direct defiance of the party.

Wang Dan remembers the emotions of that day as he watched ordinary Beijingers support the students, cajole police and form human walls to block them and protect students.

“I had tears in my eyes,” he said, “because I saw the passion of my people.”

Students went on a hunger strike May 13 and occupied the square for weeks, joined by ordinary workers. On May 18, hard-line Premier Li Peng harangued Wuer and other student leaders in a dramatic showdown on national television.

A day later, Li declared martial law. After getting a final warning to leave the square on the night of June 3, students staged a silent sit-in. Most killings occurred west of Tiananmen, where soldiers shot at protesters resisting a military advance toward the square.

“It was like a war against the people,” said one of the activists, Shao Jiang. “There was a lot of blood. I looked at the tanks and I saw they crushed some people. Looking on the road, there were human bodies, just like very thin human bodies.”

Around 4 a.m., protest leaders got agreement from a tank commander that the students on the square would leave safely.

Shao said he tried to talk to a soldier on one tank, “but the soldier just raised his gun and aimed it at me. I had to leave. I was wearing a Peking University T-shirt. It was covered in other people’s blood.”

Fang, then a talented 23-year-old athlete from Beijing Sports College, left around 6 a.m. with other students. They were walking west along an iron roadside fence.

“We knew people had been injured and died. We were leaving in an orderly way. Suddenly we heard a big bang behind us and we saw a tank fire a tear gas canister towards us. They were chasing us aggressively from the east toward the west,” he said.

“A female student walking beside me passed out because of the gas,” he added. “I was in a panic, but my instinct was to save her.” He said he managed to lift her to safety by the side of the road.

From the archives: The Times’ coverage of the 1989 Tiananmen protests and crackdown »

“The tank was suddenly right in my face,” he continued. “It happened so fast. The tank did not hesitate. It just rolled over me. I was conscious. I could feel that I was being dragged by the tank because my trousers were stuck.” He managed to free himself.

On June 5, as tanks left the square, a lone man holding shopping bags stood blocking a column of tanks, an image of courage and defiance that became a global symbol of the pro-democracy protest. His identity and fate remain a mystery.

The number of people killed is unknown. Estimates vary from several hundred to 10,000.

Students went into hiding. On June 13, authorities released a list of the 21 Most Wanted with Wang No. 1 and Wuer No. 2.

Wang fled, traveling from province to province, until he returned to Beijing and was arrested July 2. He was jailed for four years. After his 1993 release, he was constantly tailed by police as he traveled around China trying to revive the human rights movement. He was rearrested and sentenced to 11 years but was freed in 1998 and exiled to the United States. Wang lives in Maryland and recently set up a think tank, Dialogue China, designed to promote reform in China.

On July 4, 1989, Wuer and Yan Jiaqi were the first student protest leaders to escape China via Hong Kong, then still a British colony.

In August, Shao tried to flee to Macau, then under Portuguese control, but was caught, sent back to Beijing and jailed for 20 months. Released, he was harassed, followed by police and frequently detained for weeks at a time. He landed jobs, only to lose them because of police intervention. In May 1997, he escaped by walking to the border in southern China and approaching the customs post in Macau on foot. (Macau adjoins the mainland city of Zhuhai.).

Fang was finally able to leave China to settle in San Francisco in 2009. The government version of his story was that he lost his legs in a “traffic accident.”

Although the United States briefly sanctioned China, then-President George H.W. Bush wrote secretly to senior leader Deng Xiaoping within weeks of the massacre, according to his memoirs, to preserve U.S.-China relations.

The Trump administration has pivoted sharply on China, calling it a rival that has stolen from America for decades and launching a trade war.

Wang called on Western governments to reassert the importance of human rights in China.

“I feel disappointed in the West. Now, they have responded to China because China threatens them,” he said. “But at the time they could have done more.”

When he came to power, Xi launched a wide-ranging crackdown on human rights, jailing activists and their lawyers, centralizing political control, intensifying digital surveillance and abandoning presidential term limits.

Each anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown sparks debate on how to encourage Chinese human rights activists in an increasingly hostile environment.

China’s high-tech surveillance and tightening control over people’s thoughts and behavior have seen civil society shrivel, said Teng Biao, a human rights lawyer exiled to the United States in 2012.

“What possibility is there for resistance in a high-tech totalitarian state?” he asked.

ALSO:

Without memories of 1989, Chinese activists of a new generation struggle for social change

I watched the 1989 Tiananmen uprising. China has never been the same

With Tiananmen Square ‘Tank Man,’ Chinese sculptor will keep democracy’s flame alive in Mojave

For the U.S. and China, it’s not a trade war anymore — it’s something worse

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.