An Indian charity battled caste-based discrimination for three decades. Then it became a target

Reporting from Khetatimbi, India — Dudhabhai Kalabhai knew the rules: He could stand outside the village temple and join his hands in a quick, whispered prayer. He was not to linger or attempt to climb the steps.

As a Dalit, part of the lowest rung of Hinduism’s ancient caste system, his mere touch, to some, would render the shrine unclean.

But one morning in March 2015, two upper-caste villagers thought Dudhabhai ventured too close to the temple entrance. They thrashed the 70-year-old farmer with sticks, hospitalizing him with arm and leg injuries.

Family members said police in the western Indian state of Gujarat at first refused to take the case seriously. It wasn’t until the human rights group Navsarjan deployed representatives and a lawyer that the assailants were arrested, tried and sentenced to two-year prison terms.

It was one of thousands of cases that Navsarjan has fought since 1988 on behalf of Dalits, formerly known as “untouchables,” who continue to endure social stigma and economic marginalization 70 years after India’s constitution outlawed caste-based discrimination.

Now the nonprofit group finds itself under attack, accused by India’s government of harming the national interest.

In December, India’s Ministry of Home Affairs blocked Navsarjan from receiving funding from overseas, which accounts for almost all of its $400,000 annual budget. The group said it would have to lay off its 80 staff members and suspend its charitable work – including three schools educating 102 Dalit children – if the decision isn’t reversed.

The action is part of a widening Indian government crackdown against civil society organizations that critics say is politically motivated.

Officials last month canceled the foreign funding licenses of at least two dozen nonprofit groups for alleged “anti-national” activities. Besides Navsarjan, they include the Indian branch of Compassion International, which intelligence agencies accuse of secretly converting children to Christianity; a trust run by high-profile activist Teesta Setalvad, who has led court cases against Prime Minister Narendra Modi; and a legal aid office whose attorneys have represented Setalvad and other vocal government opponents.

There are few domestic funding sources for human rights organizations in India, where philanthropy outside the corporate sector is limited, meaning most rely on foreign donors. A law called the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act, or FCRA, effectively gives the government control of nonprofit groups’ purse strings – and can be used to stifle dissent.

Navsarjan staff members believe their group was stripped of its FCRA license for organizing protests last summer after seven Dalits were publicly flogged in Una, a town in southern Gujarat, for skinning a cow that had been mauled to death by a lion. Handling cow carcasses is one of many lowly occupations assigned to Dalits by upper-caste Hindus, who regard the animal as sacred. The attackers were a group of self-styled “cow vigilantes” who wrongly accused the Dalits of killing the animal.

The group also helped lead a campaign that forced investigators in August to reopen an inquiry into a 2012 police shooting that killed three young Dalit men. Four officers suspected in the case have not been charged.

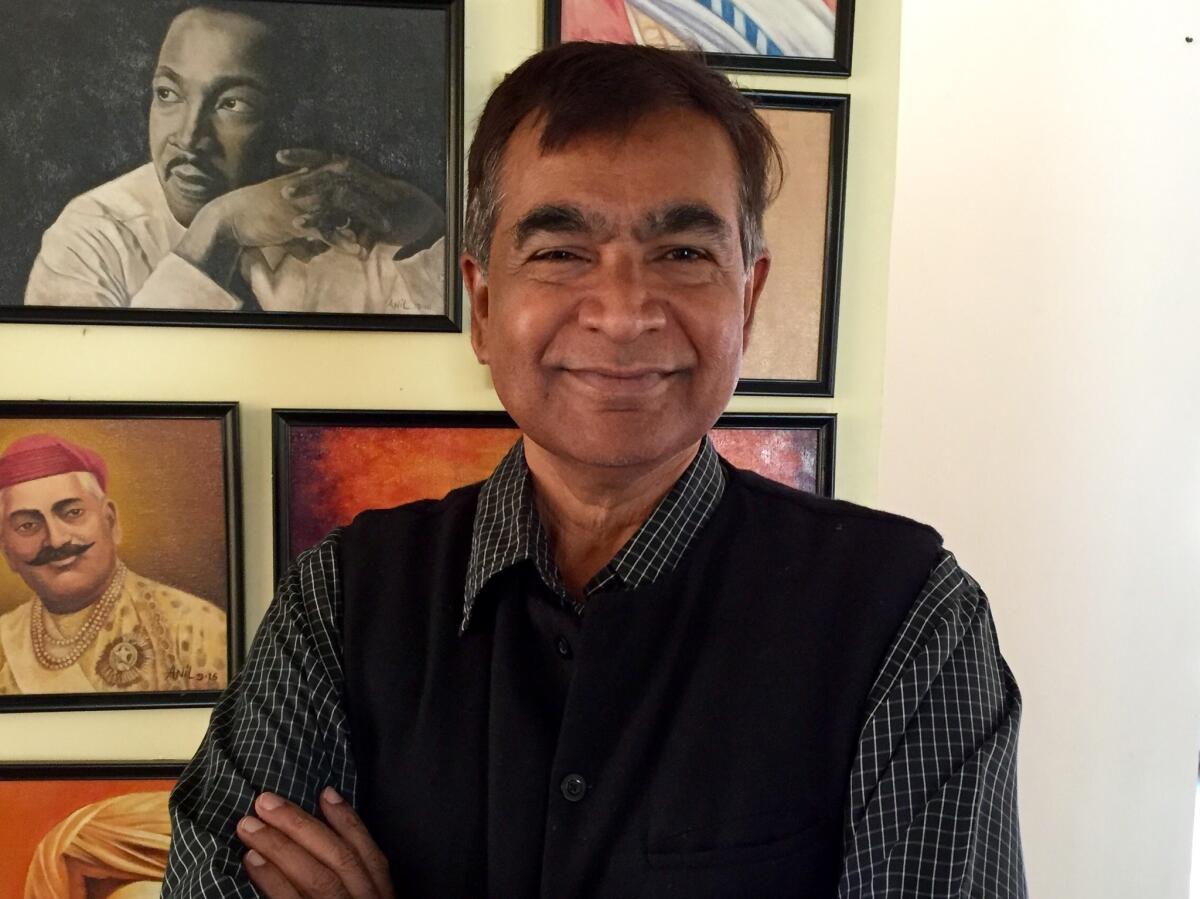

“Navsarjan put a lot of pressure, and the government didn’t like it very much,” Martin Macwan, a Gujarati-born Dalit who founded the organization, said in an interview. “They decided to hit us where it hurts.”

A spokesman for India’s home ministry, Kuldeep Singh Dhatwalia, said that “no cancellations of licenses [were] politically motivated” and the decisions were made according to the law.

Nearly half of Navsarjan’s financing comes from U.S. sources, including the Unitarian Church and Asha for Education, a volunteer group, Macwan said. Its funding certificate was renewed as recently as August, just as the Una controversy was heating up.

On Dec. 15, the home ministry abruptly canceled the renewal, saying it had been granted “inadvertently.” In a letter, it accused Navsarjan of carrying out “activities detrimental to national interest” and aiming to upset religious and caste harmony. It offered no further explanation.

The government is particularly sensitive to social unrest in Gujarat, a prosperous coastal state that Modi led until 2014, and is still run by his party. The powerful prime minister has held up Gujarat as a model of economic development, but recent protests by Dalits and other marginalized groups have chipped away at that carefully constructed image.

In parliamentary debates following the Una beatings, opposition lawmakers referred to a landmark 2010 survey that researchers from Navsarjan and the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights carried out in 1,589 Gujarat villages. The findings laid bare how many Dalits, who make up 16% of India’s 1.25 billion people, are still treated as subhuman.

Outwardly, nothing sets Dalits apart from other Indians. But caste is hereditary, and in places where the premodern hierarchy is still observed, people born as Dalits are seen as intrinsically impure, able to defile something merely by touching it.

In 90% of villages, Dalits were not allowed to enter temples, the survey found. In 53% of villages, Dalit children were seated separately from others during school lunches.

In roughly half the villages, Dalits were forced to use separate cups at tea stalls and barred from entering shops.

“This report took all the air out of the so-called ‘Gujarat model’ of development,” Macwan said. “It showed that development and inequality can coexist.”

In Khetatimbi, a hamlet reached by dirt roads three hours from the state capital, Dalits are now allowed inside the temple. But after Dudhabhai’s family complained to police about the beating, upper-caste families retaliated by refusing to serve Dalits at village shops for several months.

The harsh rural practice – known in India as a social boycott – persisted for months, until Navsarjan staff got the police to intervene.

“Before Navsarjan came, we had no awareness of our rights,” said Punnabhai, the son of the farmer who was beaten outside the temple in March 2015.

Still, there have been setbacks. The assailants appealed their convictions and were freed on bail. Last year, Dudhabhai died from an unrelated illness.

Niruben Chorsiya, a Navsarjan employee in the district, said she was working on 40 cases of anti-Dalit discrimination, including sexual violence against women. In neighboring villages, dairies regularly refuse to buy milk from Dalit cattle herders. Dalit women and girls are often barred from dances marking the annual Navratri festival, a highlight of the Gujarati calendar.

“Our work is ongoing, but how long can we continue?” said Chorsiya, who, like other staff members has been told she will not be paid after March. “It costs money to travel to villages and chase after police officers.”

India bills itself as the world’s largest democracy, but it has long nursed a deep-seated distrust of civil society groups, particularly those backed by Western countries. The previous government, led by Modi’s arch-rival Congress party, denied foreign funding to church-based groups and those that protested India’s development of nuclear energy.

The contributions law “is a sword dangling over the head of every NGO who receives foreign funding,” said Indira Jaising, a former solicitor for the Indian government whose legal aid group, Lawyers Collective, had its license canceled last year.

Jaising’s clients have included Setalvad, who has led the legal battle to have Modi convicted of complicity in deadly 2002 religious riots in Gujarat, a former police official who has offered testimony in the case, and a Greenpeace employee who was barred from traveling to Britain to speak out against the country’s use of coal-based energy.

Greenpeace had its license revoked, too, until a court intervened last month and stopped the move.

The environmental group said the law had “turned into an instrument of repression, one that the government has used to cut off vital funding to groups that may hold positions contrary to the government’s own.”

Meanwhile, Modi’s government quietly amended the funding law last year to exempt political parties, making it easier for foreign companies to contribute to Indian politicians.

Navsarjan has filed a lawsuit challenging the government’s action against it, though it could be months before the case is heard. Without an infusion of funds, its three schools will likely close when money for teacher salaries runs out in March.

At the village school in Rayka, a low concrete block building set amid budding cotton fields, 26 boys sat cross-legged on the floor, politely listening to teacher Jignesh Makwana. Several boys said they had been mistreated at government schools, forced to sit separately from other children, eat their leftovers or clean toilets.

Makwana said the students complete eighth grade at Rayka with more self-confidence and an understanding of their rights.

“We are working for the development of our community,” he said. “If the government shows us that we are somehow working against the nation, we are prepared to go to jail.”

Follow @SBengali on Twitter for more news from South Asia

ALSO

India to Amazon: We’re not your doormat

Dozens of migrants braved jungles, seas and bandits to reach the U.S. Then they were sent home

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.