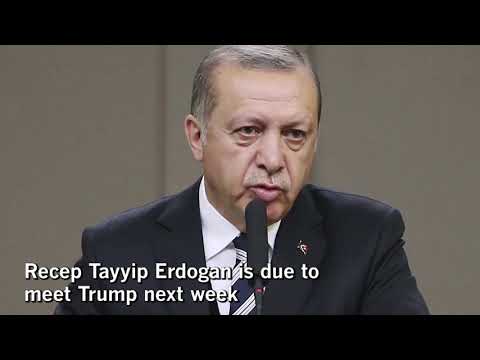

Why a Washington visit by Turkey’s president might be awkward

A Washington visit by Turkey’s president could be awkward. (May 12, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

Turkey’s President

Although Turkey is a NATO ally and a key partner in the fight against

Here’s why:

1. Kurds and dismay

Turkey responded angrily to a Pentagon announcement this week that the United States would move to equip and arm Kurdish fighters in Syria. The U.S. has long had a relationship with the YPG, or People’s Protection Units, operating under the umbrella of a larger armed Syrian rebel faction. Turkey, though, considers the YPG fighters to be terrorist comrades in arms of separatist Kurds across the border in Turkey, and tensions have been growing over the YPG’s role in the looming battle for Raqaa, capital of Islamic State’s self-declared caliphate. Turkey’s prime minister, Binali Yildirim, warned Wednesday that tighter U.S. ties with the YPG could lead to an unspecified “negative result.” Erdogan was quoted by Turkish media as saying he hoped the U.S. decision would be reversed at the earliest possible opportunity. Trump, then, needs to keep the Turkish leader close without undercutting his own military commanders, who consider the YPG the most effective allied ground fighting force in the confrontation with Islamic State.

2. Hail to the chief

Last month, Erdogan claimed victory — though a narrow one — in a nationwide referendum to vastly expand his constitutional powers. Although most Western governments and human rights groups viewed the measure as a heavy blow to democratic aspirations in Turkey, and although opposition parties challenged the result, Trump swiftly placed a congratulatory phone call to the Turkish leader. While that might have helped put the two men on a good personal footing, it played into the narrative of Trump as an admirer of authoritarian-minded leaders and a less-than-enthusiastic defender of democracy and human rights, both of which were previously pillars of U.S. foreign policy. Erdogan, meanwhile, continues to lash out at political foes as he smarts over failing to score a decisive win at the polls — a stance in some ways reminiscent of Trump’s continuing sensitivities over his receiving fewer popular votes than Hillary Clinton despite winning the electoral college vote.

3. Fugitive from justice?

After Erdogan emerged victorious from an

4. Flirtation, or something more?

In the past, Turkey has reliably responded to tensions in its ties with Washington by making overtures to Moscow. Erdogan and Russian President Vladimir Putin have had their ups and downs, but they staged a very public reconciliation in August 2016, after nearly a year of sanctions-marked estrangement following Turkey’s shooting down a Russian fighter jet on the Syrian border. Russia and Turkey still remain on opposite sides of the Syrian conflict; Putin is the principal ally of Syrian President

5. Blurred lines

Although Trump says he has formally separated himself from his far-flung business empire, ethics experts say the president has not gone nearly far enough. So there is continuing scrutiny of political decisions — particularly in the foreign arena — that could affect Trump’s personal and corporate financial interests. Turkey is a major case in point: critics including U.S. Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Burbank), the ranking member of the House Intelligence Committee, have expressed concerns over Trump Towers Istanbul — a massive two-building complex in Turkey’s commercial capital that Trump does not own, but with whose developers he struck a major licensing deal. Trump’s sons, who now run the Trump Organization, have recently pursued a hotel-chain project with the backing of a Turkish-linked real estate firm. Finally, lucrative consulting work for the Turkish government by Trump’s fired national security advisor,

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.