I Gotta BE Me : Careers: Aptitude testing is booming as more people strive to trade in the treadmill for personal satisfaction.

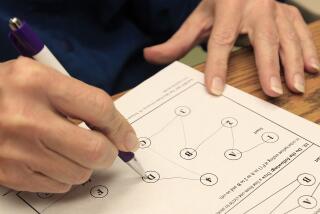

Imagine a cocktail napkin. Fold it into an unusual geometric shape. Then take a paper punch and poke a single hole through the folds.

Now, without opening the napkin, indicate on a chart where the holes will appear when the napkin is unfolded.

It’s torture. David Lyon may as well have asked for a quick sketch of a breeder reactor.

The paper-folding task is typical of several tests given over the course of two days at the Johnson O’Connor Research Foundation’s Human Engineering Laboratory.

The nonprofit foundation is a center for aptitude testing, perhaps the best known of a growing number of organizations and businesses where adults--dissatisfied with their careers in early middle age, or simply feeling a vague sense of potential unfulfilled--pay $450 to both confirm and uncover their true aptitudes.

The foundation has tested about 300,000 people since architect and aptitude researcher Johnson O’Connor first began administering tests to employees of the General Electric Co. in 1922.

“Most of the people who come to us in their late 30s and early 40s come because they’re not satisfied with what they’re doing,” said Lyon, director of Johnson O’Connor’s Los Angeles office (there are 15 offices nationwide). “It isn’t so much that they are feeling as though they’re not capable of doing what they’re doing, but that something is not quite right.”

The paper-folding test is the fourth in Johnson O’Connor’s battery of 23 tests. It tends to make people who work with ideas and concepts want to scream, said Lyon. For engineers, it’s duck soup.

The first day begins with a set of individual tests administered by Lyon, starting with two simple tests for color perception and hand and eye dominance, or “laterality.” (Are you right-handed or left-handed and which eye do you favor?)

Then it’s into the trenches, beginning with a test for observation. Lyon holds up a photo containing 20 common household objects--a button, a safety pin, a coin purse and the like--and you get to look at it for one minute. The picture then is taken away; a new one is shown, similar to the first. You must tell which objects have disappeared or moved to a different location in the picture.

There are several different examples, and you get to look at the first photo--the “master”--for 12 seconds before each new photo is shown. Your responses are timed.

The paper-folding test follows, of which the less said the better. Unless you’re Frank Lloyd Wright.

Want to be a surgeon? Then score high on the next one: tweezer dexterity. Lyon presents a brick-sized block with 10 rows of 10 small holes drilled in one side and an identical number of holes and rows in the other. Your job: Pick the pins out of the holes on one side, one at a time, with a pair of tweezers and place them in the corresponding holes on the other side. You’re timed. This test tends to make your eyes bug out.

Aptitude testing used to be associated with students rather than middle-aged adults. Testers say the ethic that governed the working world did not make any allowances for a career change.

“Part of the developmental process is that people have different needs at different points of their lives,” said Albert Aubin, a senior counselor at UCLA’s Placement and Career Planning Center. “A 22-year-old who makes a career decision makes it on the basis of the values that are necessary at that age. Those values do indeed change by the time that person is 35.”

A kind of career inertia, coupled with “almost a stigma attached to people who made career changes” often lock people into jobs with which they were unhappy, said Aubin.

“But people are now taking a much more active role in their career development,” he said. “They’re seeing that change is OK. This has become much more acceptable.”

Helen Hewitt, a former high school teacher and career counselor who runs the education and career counseling firm Career Prep Enterprises in Brea, said that in the last five years, her number of adult--as opposed to student--clients has grown from 10-15% of her business to about 50%.

“We’re finding that people are not really happy, excited, passionately in love with what they’re doing,” she said. “They need to get quality in their lives. A lot of people fall into a career, and, all of a sudden, when they hit about 35 or 40, they say, ‘What am I doing? I’m getting up in the morning and I don’t want to go to work.’ It’s a drag.”

At Johnson O’Connor’s Los Angeles office, about two-thirds of those tested are adults in transition, generally from age 28 to 40, said Lyon, adding: “People are simply saying, ‘I don’t need to do (what I’m doing). It’s more important to do something that makes me happy and I have to find out what it is.’ ”

You get three tries at the Martian words. On a screen, you are shown, one by one, 20 nonsensical (but pronounceable) words and their English equivalents (example, lokar: clock). After the last words are flashed, you turn over a piece of paper on which the “Martian” words are written. You provide their English translations from memory. The test is repeated two more times to see how your memory for words improves.

After a quick test to see how fast you can write--it will come into play later--comes the first of the auditory tests: pitch discrimination. A pair of electronically generated musical tones is played through a headset and you decide if the second tone was higher or lower in pitch than the first. Of course, it gets progressively harder, so that near the end the pitches are only a few vibrations apart on the tonal spectrum. There is much knitting of brows in the room (it’s a group test) and, oddly, squinting and leaning forward, as if such actions would help anyone hear more clearly.

More musical testing follows with the rhythm memory section. Increasingly difficult rhythm patterns are played into your headset. Each pattern is followed by a second one, which is either the same as or different from the first; you have to decide which. After a while, it all begins to sound like a telegraph key.

Aptitudes aren’t skills, and they aren’t knowledge. They can’t be learned. They are innate abilities for learning to do certain things, and the prevailing belief is that they are inherited, said Lyon.

“They’re also needs, like eating and sleeping,” he said. “If you have them and don’t use them or if you place yourself in situations that call for those you don’t have, you’ll know. It will cause you anxiety and you may not know why.”

Many professionals, particularly lawyers, are frustrated, said Lyon, because they embraced their profession in deference to money or status or pressure from parents or peers, and ignored their aptitudes.

He recalled a lawyer who tested at the fifth percentile in inductive reasoning (“the area most needed for law”), but tested high in innate creativity and scored in the 85th percentile in structural visualization. Lyon said the man chose law because he believed it was a traditional progression from his undergraduate work at Yale.

“I told him he should be building things,” said Lyon. “He smiled and said he had a workshop at home and generally he spent the whole weekend there working in his shop. I think he’s going into engineering.”

Day two begins with every humanities major’s delight: numbers. Specifically, the number series and number facility tests. The first requires you to read several sequences of six numbers and write in the next logical number at the end of each sequence. The second involves arranging--against the clock--small groups of numbered chips into simple addition and multiplication problems. The first test measures how well you know your higher math, the second how well you balance your checkbook.

Next is a test--word association--to determine personality type. The results indicate whether a person has an objective or subjective personality (75% test objective). Objective people tend to be generalists, taking in a broad, encompassing point of view and usually working with, around or through other people. Subjective people tend to be specialists or experts, often working alone.

However, said Lyon, personality traits that reveal themselves through this testing “only apply to the work situation; in your personal life you could be completely the opposite.”

The next test for inductive reasoning--identifying pictures in a series that are related to each other in some way--is the one Lyon said he considers the most significant of all. It is the ability to reason from the particular to the general, to see the relationships among a mass of ideas. In short, diagnostic thinking--a need to solve problems.

“It’s a very dangerous aptitude,” said Lyon, “because people who have it and don’t use it are always finding fault with everyone and everything around them. They can’t help themselves. It’s just picky, picky, picky.”

Aptitude testing is not universally accepted as the best or only way to plot one’s professional future.

“It seems to me like a very old-fashioned approach,” said Jon Snodgrass, a psychologist who teaches human development and organizational behavior at Cal State Los Angeles and operates a career counseling business in South Pasadena called Career Strategies Center.

Snodgrass said he uses information gleaned from personal interviews with clients to determine whether they are dominated by their left brain (the rational, calculating side) or the right brain (the creative side). He then designs specific exercises to help produce a balance between the emotional and the rational. Those heavily influenced by their left brain may become scientists but long to be musicians. However, said Snodgrass, they may not know the source of their dissatisfaction because they aren’t naturally intuitive. Right brainers may be too emotional or undisciplined to make truly insightful career decisions, he said.

Structured testing, said Snodgrass, is, for left-brainers “like putting leeches on a bleeding person.” It will do nothing to tap into their creative, insightful side.

At the UCLA Placement and Career Planning Center, testing also is informal and not standardized. Aubin said two of the areas of greatest concentration at the center are what he called job satisfaction and work values--what people want out of their jobs.

For instance, said Aubin, “if a person doesn’t feel his current skills and abilities are being used, and that is a very important work value that he wants, there’s going to be a lot of dissatisfaction. If recognition is important, and he’s in a position where the boss gets the recognition, he won’t be satisfied. You can have a very strong aptitude for something and still not like it.”

The center does use two specific tests that have become increasingly popular among career counselors: The Strong-Campbell interest inventory (to determine the types of activities people like) and the Meyers-Briggs personality indicator (to classify a person’s personality into one of 16 types).

Aubin said he didn’t discount aptitude testing.

“It’s not that we’re against it,” he said. “Aptitude tests are important. But you need a more complete picture.”

There are more clenched jaws when the test measuring memory for design is administered. A geometric-type line drawing is projected on a screen for 12 seconds. It then disappears. You have 45 seconds to reproduce it by connecting a series of dots on a piece of paper. There are several examples, and the eyes in the room stare harder and harder at each one, memorizing, memorizing.

Six more projected images follow, again simple drawings. You make a list, during the 45 seconds each image is on the screen, of what the drawings remind you of. The longer the list, the higher your foresight, which is the ability to keep your mind and actions on a distant goal.

The final test is for tonal memory. A series of electronically generated musical tones is played into your headset--first only three, eventually eight--and a second set is played immediately after. You circle the number on your test sheet that corresponds to the note in the sequence that changed in the second set of tones. The testees do not sigh when this one is over; there is an almost explosive exhalation of breath and everyone slumps heavily against the backs of the chairs.

Salesmen who might be psychologists. Lawyers who might be carpenters. Writers who might be diplomats. It’s all hashed out in a final afternoon session at Johnson O’Connor.

There may be no absolutes, but the results can be telling. If, for instance, your profile indicates an unexpectedly high score on memory for design and your current job matches well with the rest of the profile, Lyon might suggest drawing as a hobby. If, however, you scored unusually high in inductive reasoning and you work on an assembly line, you may be urged to look for a different job.

But it’s not a question of use it or lose it, he said. It’s a question of use it or be unfulfilled.

“With an aptitude,” he said, “you’ll never lose it. It’s always been there. It’ll always be there. It isn’t influenced by where you were brought up or by how much education you have or in what areas you have it. It’s just there. An aptitude is like a kid. If you have a child and you don’t pay attention to it, it gets in trouble.”