Gene Therapy Trials OKd by Health Panel

BETHESDA, Md. — The first government-authorized attempts at human gene therapy cleared a crucial hurdle Monday, and researchers said it meant that sick children and cancer patients may be able to benefit from them by year’s end.

The National Institutes of Health’s Human Gene Therapy Subcommittee granted, 12 to 1, permission for NIH researchers W. French Anderson and Michael Blaese to use gene therapy to treat children stricken by the rare immune system disorder that afflicted the famed Texas “bubble boy.”

The committee also unanimously approved a plan of Dr. Steven Rosenberg of the National Cancer Institute to insert a gene that codes for tumor necrosis factor--a substance that has dramatically shrunk tumors in mice--into tumor-fighting immune cells removed from cancer patients, multiplied in the test tube and then returned to the patients’ bodies.

Jeremy Rifkin, president of the nonprofit Foundation on Economic Trends in Washington, criticized the NIH approval as premature.

“We have a technology that is speeding into application without any of the appropriate ethical and social issues being raised,” said Rifkin, who has long called for tight regulation of genetic research practices to guard against abuses.

Rosenberg said he could begin treating about five patients who have melanoma, a deadly type of skin cancer, within a month of receiving final approval from the Food and Drug Administration.

Rosenberg’s work, unlike Anderson’s, is designed to find out if the treatment would be safe, not if it would be effective.

Although both researchers hope to use gene therapy to treat relatively rare diseases, their work could lead to development of new treatments for a wide variety of illnesses.

Each human body has about 100,000 genes, which control everything from eye color to tendencies to develop certain diseases. Gene therapy involves inserting genes with correct information into cells that contain defective genes, or inserting new genes to introduce coding for disease-fighting substances.

“This committee, historically, has been our largest obstacle,” Anderson said. He added that he would not celebrate a victory until the full Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee of 25 votes on the plan today.

The gene therapy plan also needs the approval of the director of the National Institutes of Health and the FDA, but Anderson said that the NIH advisory panel was the largest hurdle.

If no further roadblocks are encountered, Anderson said, he expects to start transferring genes into human patients by late fall.

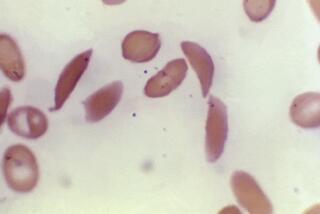

The NIH team wants to correct a rare childhood immune system deficiency, caused by a defective gene that lacks coding for the enzyme adenosine deaminase, by inserting correct copies of the gene into patients’ blood cells.