Fights Common at Troubled Company : Tailored Baby: An ex-executive is accused of setting fire to its factory. He says he later shot and killed the owner of the firm in self-defense.

It was a Monday in February and a typical day at Tailored Baby Inc. in San Fernando. Aaron Thomas, owner and president, and Victor Soto, his vice president, were having a fight.

During the argument, employees said, Thomas held a hammer, and he kept threatening Soto with it. Soto kept a .38-caliber pistol in his desk and he finally used it, firing several shots into the floor as a warning to Thomas. Police later found the bullet holes.

The next day things got worse.

Aaron Thomas issued a companywide memo saying he had fired Soto and changed the locks on Tailored Baby’s doors. But Thomas asked Soto to come back that evening, apparently, police said, to discuss their differences.

At 7:30 p.m., Thomas, 47, lay on the floor of Soto’s office--among the dainty pink and blue quilts, blankets and bibs that the company makes--bleeding to death from several gunshot wounds. Soto, also bleeding from a hammer blow to his head, called police. Soto said he shot Thomas after the company owner attacked him and hit him on the head with a hammer, police said.

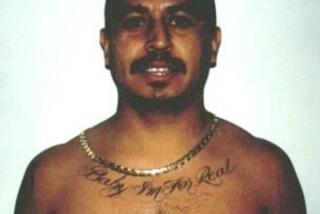

A weeping Soto, 36, was taken into custody after being treated at a hospital. He was later released, and the investigation of the killing has continued ever since.

Last Thursday, Soto was arrested at San Fernando police headquarters. But the charge was not murder. It was arson, grand theft and insurance fraud.

According to the Los Angeles Fire Department and federal investigators, Soto started a fire Dec. 18 that destroyed one-third of Tailored Baby’s factory. Damages have been estimated at more than $1 million.

By the time Soto was arrested, Los Angeles Deputy Dist. Atty. Michael J. Cabral explained, federal and city authorities had discovered that Soto had told an insurance company that he and Thomas had cooked up the arson scheme to collect insurance money to bail the firm out of its financial troubles.

Cabral said he’s seen it before: Once a challenger to larger competitors such as Fisher-Price and Spalding & Evenflo, Tailored Baby had suffered a series of setbacks in recent years and was on the brink of bankruptcy. Arguments among company executives, already a regular occurrence, grew more frequent.

When a company is in trouble, officials occasionally turn to desperate and illegal means to try to solve their problems, Cabral said. When that happens, he said, “The whole house of cards falls down around you.”

Certainly the company’s financial problems were acute. According to an audit by the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms conducted as part of the arson investigation, Tailored Baby’s sales fell 25% from 1989 to $15 million in 1990, and it had $2 million in unpaid debts.

Cabral said that on the night of the fire, a meeting was scheduled for Thomas, Victor Soto and Walter Soto--Victor’s brother, also an employee--and accountants to discuss filing for bankruptcy protection. As the meeting convened at a local restaurant, Tailored Baby was literally burning down.

Investigators later found that the Tailored Baby plant had been doused with gasoline, Cabral said. A witness saw a man jump from the roof at the time of the fire, curse when he hit the ground, and limp away. Victor Soto never made it to the meeting with the accountants, Cabral said, because he was being treated at a local hospital for a broken ankle.

Tailored Baby’s insurer, Cigna Corp., paid a $500,000 advance to the company after the fire, Cabral said. A few weeks ago, Victor Soto contacted Cigna, which has also been investigating the fire, and offered to tell how the fire started if the insurer would pay for his defense, Cabral said. Cigna didn’t agree to the deal, Cabral said. Cigna officials declined comment.

Other suspects are still under investigation in the fire, Cabral said, but the possibility of Aaron Thomas’ involvement wasn’t pursued after he died.

Roger Thomas, Aaron’s brother and Tailored Baby’s manager of manufacturing operations, and the company’s new president, Kenneth Braun, declined to comment on Soto’s arrest. But a company spokesman said “neither of them believe Aaron was involved with the fire in any way.”

Soto declined to be interviewed for this article. He faces up to 14 years in prison for the arson-related charges. He remained jailed Monday in lieu of $250,000 bail; a hearing has been set for May 9.

Meanwhile, the investigation into Thomas’ death remains open. Lt. Rico Castro of the San Fernando police said the arson charges have no bearing on that investigation. But Castro said he believes that Soto killed Thomas in self-defense.

Castro said he initially suspected that Thomas and Soto were arguing the day before Thomas died over “who was going to take the fall for the arson.” But after talking to witnesses, he said he concluded that the argument was not specifically about the fire, but was rooted in “personality problems” and aggravated by the financial woes.

Roger Thomas was in South Carolina when his brother died, and said he would “reserve judgment” on the circumstances surrounding the shooting. Margaret Thomas, Aaron’s widow and Tailored Baby’s present owner, declined to comment.

Thomas, a short, stocky man who grew up in the South, the son of textile workers, bought Tailored Baby--then a tiny operation in a garage--14 years ago using advances on his credit cards. For years, he worked 16-hour days and plowed profits back into the business, said Roger Thomas.

Braun blamed much of Tailored Baby’s financial troubles on the recession, which hurt retailers such as Ames Department Stores, a big customer that is now in bankruptcy proceedings.

But Maura Davis, spokeswoman for the Juvenile Products Manufacturers Assn., a trade group, said the recession hasn’t been a big problem for the other 300 baby products suppliers. Industry sales grew 16% from 1988 to $2.25 billion in 1989, Davis said. Although 1990 sales figures aren’t in yet, last year 4.2 million babies were born, the highest number since 1964--a good sign for baby products companies, she said.

Claudia De Simone, publisher of Juvenile Merchandise, a trade publication, had another explanation for Tailored Baby’s decline: The company’s expansion, including a 1989 acquisition of a plant in Alabama, left the company short of cash, she said.

Federal and state recalls of two products also hurt. One recall involved an infant cushion that didn’t contain flame-retardant foam, as required by state law. In August, 1989, the state ordered Tailored Baby to stop making the cushion, conduct a costly recall program and pay $100,000 in penalties. Braun said $80,000 of the penalties were stayed because the company cooperated with the recall. He said the foam had been manufactured by another company, and Tailored Baby hadn’t known when it bought the foam that it wasn’t flame-retardant.

Last year, Tailored Baby was also part of a voluntary recall of bean-bag style cushions initiated by the federal Consumer Product Safety Commission. Elaine Tyrrell, a CPSC spokeswoman, said Tailored Baby was not implicated in any infant deaths associated with bean-bag cushions. But it did join in a refund program and poster campaign warning the public of the dangers of these cushions.

Employment at the company’s plants in San Fernando, Alabama, South Carolina and Mexico is down to about 270 from more than 500 at its height. Mass merchandisers such as Wal-Mart and Target Stores are among Tailored Baby’s biggest customers. But lately, said George Hite, a Target vice president, “the difficulties they’ve encountered have demonstrated themselves in their inability to meet shipments.”

As Tailored Baby’s condition worsened, fights were common among executives, Castro said. “Employees wouldn’t take any notice if they came out fighting and slugging each other. They’d just go back to typing.”

Last June, when Castro saw Thomas about an employee-theft case, Thomas had a cast on one hand. Castro said Thomas told him that his hand had been broken in Mexico during a fight with people who had tried to steal his money.

Even among other baby products makers, Thomas was known to be volatile. An executive at another baby products company, who asked not to be named, said Thomas often took up with great fervor causes that others in the industry considered trivial, then suddenly dropped the issues without explanation. “He certainly had enemies,” added Paula Markowitz, president of Patchcraft, a New Jersey infant bedding company.

Braun, 43, an attorney who represented Tailored Baby for six years, said he must now assure customers, suppliers and employees that the firm can recover. He said he plans to eliminate unprofitable products and expand sales abroad.

Recently, workers began rebuilding the burned-out part of Tailored Baby’s plant, and manufacturing at the facility--idled since the fire--has resumed on a much smaller scale.

Aaron Thomas’ key-man life insurance policy will help Tailored Baby survive, Braun said. He wouldn’t say how much the company collected from the policy, but he said the proceeds have helped reduce debt and would “give us the opportunity to commence our recovery.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.