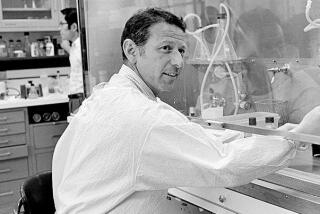

Amgen Founder Tries to Clone Success : Biotech: George Rathmann changed his retirement plans and is now chairman of another infant firm.

George Rathmann spent the 1980s nurturing tiny Thousand Oaks-based Amgen Inc. from a vague idea into the nation’s most successful biotechnology company. His goal for the 1990s was simply to retire.

So why is Rathmann, now 63, working as hard as ever trying to duplicate his Amgen triumph as chairman of Icos Corp., another infant biotechnology company?

“There’s an irrational element in this,” Rathmann conceded about his retirement detour. He said he discovered that “not being in the operation of a business is not OK if you’re a person like me.”

Investors seem willing to bet that if Rathmann worked magic at Amgen, then maybe he can do the same for Bothell, Wash.-based Icos, which is developing anti-inflammation drugs.

Ned Hamarat, president of Beekman Capital Management Ltd. in New York, loaded up on 250,000 shares of Icos’ stock in June. “Basically this is a concept company,” Hamarat said. “You’re buying people. More than anything else George Rathmann was the primary reason” to buy.

Rathmann’s marquee value helped Icos raise $64 million from private and public stock offerings in the past two years--including $5 million put up by William Gates. The billionaire founder of computer software giant Microsoft now owns 8% of Icos’ stock.

In June, Icos’ stock went public at $8 a share, and it closed Monday at $18.50, in part because Amgen’s surge has lifted up many other biotechnology stocks.

Philip Whitcome, Amgen’s former strategic planning director, said he believes that Rathmann accepted the chairmanship of Icos in January, 1990, in part to disprove the theory that Amgen was built on luck, not skill, “and George wanted to duplicate its success.”

But the road to success is not without its bumps. Icos’ Chief Executive Robert Nowinski quit suddenly last month, requiring Rathmann to take on the additional duties, a role he apparently had not envisioned at the outset. Although Rathmann won’t go into the details, industry sources believe that there was a battle between the pair, and in the end Nowinski went out the door.

Investor Hamarat speculates that Icos’ founders were executives with “very, very large egos. And could that many giants stay in a room together? The answer is no.”

In fact, others have complained that Icos was conceived more as a celebrity enterprise than as a scientific operation. Icos’ board now includes Walter Wriston, former chief executive of Citicorp, Frank Cary, IBM’s former chief executive, a former head of General Foods, a past secretary of commerce and Gates--all notable figures, but none, Icos’ critics note, are biotechnology experts.

David Stone, a biotechnology analyst with the investment firm Cowen & Co. in Boston, said: “I’m skeptical of an organization where the genesis of it seems to be financial promoters and people who lent their names like Wriston and Gates, and three recycled biotech executives. Did these executives join the organization because this group of scientists have a unique handle on diseases, or they were all mutually persuaded that this was a marketable idea?”

And Icos’ founders have been criticized for the size of their personal stakes in the company. Last year, an executive with Paine Webber Inc., which underwrote Icos’ private stock sale, reportedly complained that the Icos’ founders, including Nowinski, Rathmann and scientific director Christopher Henney, were getting too much of a good deal. While putting up little money themselves, the three control 18% of Icos’ stock. Their compensation included annual salaries of at least $176,000, plus 10% yearly pay raises and eligibility for 40% to 60% annual bonuses.

The founders’ relatively small investment doesn’t upset Hamarat: “In small companies it’s not so unusual that the brains contribute the brains and the money people contribute the money,” he said.

Now that Icos has raised the money, Rathmann plans to “bet heavily on science, science, science.” Icos has a team of about 60 scientists, and they are trying to crack an entirely different scientific mystery than Amgen did.

Each of the 15 or so biotechnology drugs and vaccines now sold in the United States are liquids--they contain gene-spliced copies of large protein molecules found in the body--which must be injected into patients. This compares to typical pharmaceutical drugs in pill forms with such small molecules that they pass through the digestive tract without losing potency.

One of Icos’ goals is to blend the science of biotechnology and conventional pharmaceuticals to create drugs in pill forms that can stop chronic inflammation. It’s a vast scientific quest because inflammation is a symptom common to debilitating diseases ranging from multiple sclerosis to rheumatoid arthritis and asthma.

One obstacle to accomplishing Icos’ scientific goals, Rathmann said, is that “we lack is a chemical library and a broad group of chemists.”

Glaxo Holdings, a British company that is the third-largest pharmaceutical powerhouse in the world, has both. Icos earlier this month signed a joint development project with Glaxo to share research on many of Icos’ projects. If all goes well, Rathmann said, Icos’ first drug project might be ready for human tests by the end of 1992.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.