A Buy-Sell Pact Can Protect Family Businesses Amid Feuds

The screaming match in the executive office that Friday afternoon was hateful in the way only brothers and sisters can be when they fight.

Bitterness and recriminations flew as the younger siblings vented years of frustration with their older brother, the chief operating officer, accusing him of not pulling his weight at the growing company. Anger boiled over as the brother blasted his younger brother, the president, and sister, the director of purchasing.

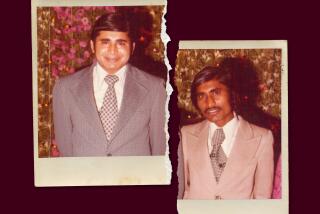

“It was hair-raising,” said Judy Sterling, a co-owner of Pasco Specialty & Manufacturing Inc. in Lynwood.

Furious, her older brother quit the plumbing supply company his father had bought in 1964.

It could have been the classic start to the long and nasty process that many family businesses experience when a family member leaves in anger or some other event, such as death, divorce or disability, threatens to upset the balance of power.

Sterling, 57, credits one thing for saving her company, and family, from that fate: a document drawn up years earlier that laid out how and when the company would buy back family members’ shares, how much would be paid and how fast. It’s called a buy-sell agreement.

While it’s not a guarantee against friction, a solid, up-to-date document can smooth the way during difficult family transitions, as well as protect the company from legal battles and punitive payments.

“A buy-sell agreement is imperative,” said Gary Boudreau, director of succession planning in Southern California and Nevada for accounting and consulting firm Deloitte & Touche.

Without clear guidelines on how the family’s stock can be sold, including who can buy it, a family can be torn apart by acrimony that can last for generations, said Boudreau, who is based in Costa Mesa. That can prove fatal to a family business.

“It saved the day,” Mike Hite, president and co-owner of Pasco and Sterling’s younger brother, said of the company’s buy-sell agreement. His brother’s departure in 1995, his father’s death a few years previously--”any of those things could put any business out of business,” said Hite, 39. “Because of our buy-sell agreement and planning, we are still here. We didn’t miss a beat, other than the personal beat.”

To be effective, an agreement needs to be put in place early and “dusted off often,” said Bill Simpson, a partner in law firm Paul Hastings Janofsky & Walker. In 20 years as a corporate attorney, Simpson said, he has drawn up dozens of buy-sell agreements.

At Pasco, Sterling got the ball rolling when she joined the company in 1985 at her father’s urging. She wanted a buy-sell agreement for several reasons. She didn’t own company stock at the time and wanted rules to guide the sale of it when the time came for her father to retire. She wanted a way to fund her own eventual retirement (by having the company buy any stock she eventually owned) and she wanted to protect the company. She and her brothers had watched in dismay as a separate business run by two of their uncles went down in flames when a fight over assets after the death of one of the uncles ate up all those assets.

Her dad was against the idea.

“He said that if we were family and loved each other, then when somebody left there would be compassionate behavior and things would be taken care of,” Sterling said. She argued that “because we are family, we have to be compassionate going into this, and we have to protect the business.” Her brothers agreed.

What finally helped win her dad over was the buy-sell agreement’s ability to protect the company from the prospect of a predatory spouse if one of his children divorced.

“We didn’t want an opportunity for a spouse to come in on the death of one of the partners and take over,” she said. “That really helped push it through.”

The agreement, put together with the help of a lawyer, allows the company to pay a family member for their shares over a period of up to 15 years. Like many such agreements, it calls for annual interest payments on the principal, then a lump sum at the end of the period. For their older brother, Dennis, 59, they decided to speed up the process, paying him principal and interest over five years.

“Do it at a time where people aren’t in an adversarial mode,” Simpson said. If no one knows what side of the agreement they might be on in the future, the guidelines will tend to be fairer, he said.

Some companies add a punitive twist, cutting the value of shares if a family shareholder leaves the company under negative circumstances. Many, like Pasco, use a formula accepted by the Internal Revenue Service to value the shares. Whatever method is used, it should be evaluated and the company’s worth refigured every six months to two years, depending on how fast things are changing in the family and the company.

The older brother could have demanded a new valuation of the company when he left, Simpson said, but decided against it because of the expense. Valuing a closely held company can cost $10,000 to $30,000, according to Boudreau.

“I didn’t want to make any more waves than I already had,” said Dennis Hite, now retired in Reynoldsburg, Ohio. He agreed with his siblings’ assessment that health problems, including constant headaches from an earlier accident, had kept him from performing up to par.

The smooth stock buyback, and the perceived fairness of the transaction, helped the brothers and sister begin to mend their relationship, the siblings said.

Sterling is now advising her son-in-law to put one in place at his father’s company.

“I’m a cheerleader for this,” she said.

*

Columnist Cyndia Zwahlen can be reached via e-mail at cyndia.zwahlen@latimes.com.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.