Genentech Co-Founder Testifies For Firm

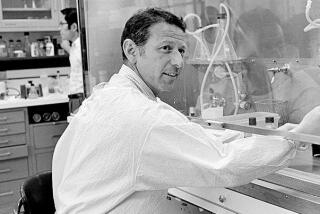

Genentech co-founder Herbert Boyer testified in Los Angeles Superior Court on Monday that he initiated the collaboration with City of Hope National Medical Center that led to the breakthrough discovery of human insulin.

But Boyer, a respected former UC San Francisco scientist, said he did not negotiate the disputed 1976 contract between Genentech and City of Hope and is not aware of its details.

Boyer testified on behalf of Genentech, which opened its defense in the $500-million civil lawsuit Monday.

City of Hope, a prominent cancer center in Duarte, claims that Genentech for years has cheated it out of royalty payments.

Genentech, which has paid City of Hope more than $285 million in royalties, claims the hospital wants to rewrite the contract before the deal effectively expires in 2003.

Boyer is retired from Genentech, but remains a corporate director. He said he recruited City of Hope scientists Arthur Riggs and Keiichi Itakura to develop technology needed to produce human insulin. But Boyer said he did not negotiate the contract, which was handled by deceased Genentech co-founder Robert Swanson.

Boyer praised the skill and intelligence of Riggs and Itakura, but stressed the research was a collaboration between City of Hope and UCSF scientists, whom he said played a bigger role. Genentech had no scientists of its own at the time.

UCSF scientists executed five crucial steps that led to the breakthrough, Boyer testified. City of Hope scientists handled just two steps in the process, he said.

The contract between City of Hope and Genentech predates the biotechnology industry. Genentech, then a start-up company, agreed to fund research at City of Hope. The hospital, in turn, agreed to assign patents to Genentech in return for royalties on sales of drugs that resulted from the research.

Through 1999, Genentech paid City of Hope royalties on human insulin produced by Eli Lilly under a now-expired licensing deal. It continues to pay City of Hope royalties on a second drug produced by Genentech, human growth hormone.

But City of Hope claims that South San Francisco-based Genentech owes it royalties on up to 27 other drugs under licensing deals that it hid from the medical center. City of Hope rested its case Monday before Boyer testified.

In previous testimony, City of Hope attorneys interrogated Sean Johnston, Genentech intellectual property vice president, as an “adverse witness” about five key licensing deals.

Johnston said under questioning that in 1990 Genentech told Eli Lilly that it had licensed the patents, known as Riggs-Itakura patents, to SmithKline Beecham for hepatitis B vaccine, Monsanto for bovine growth hormone, Hoffman LaRoche for interferon, among others. City of Hope did not receive confirmation of those deals from Genentech until the second day of the trial.

But Johnston said City of Hope isn’t due a royalty unless other conditions of the contract are met. Genentech contends that City of Hope is entitled only to royalties on drugs it helped develop, namely insulin and human growth hormone.

City of Hope maintains that a licensing deal by itself triggers a royalty. The patents cover a method of inducing bacteria to produce a human protein.

“If they are relying on my testimony, it is a pretty sad commentary on their case,” Johnston said outside the courtroom. He asserted that City of Hope filed the suit because all royalties will end when the Riggs-Itakura patents on human growth hormone expire in 2003.

City of Hope general counsel Glenn Krinsky has said the expirations of patents are not a motivation.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.